This excerpt is brought to you by a partnership between Baseball Prospectus and the Pandemic Baseball Book Club, a collective of baseball authors focused on the principle of cooperation over competition. Check out their conversations about baseball books and much more at pbbclub.com, and on Twitter at @pandemicbaseba1

Chapter 5: War

1944–1945

Chief Warrant Officer Gary Bodie was right. By the spring of 1944 he’d lost several top players from his Norfolk Naval Training Station baseball team, including Phil Rizzuto, Dom DiMaggio, and Eddie Robinson. All three were shipped out to the South Pacific for active duty. But Yogi’s call from Bodie never comes.

Instead, Yogi receives a phone call from the Red Cross during his six-week basic training in Bainbridge, Maryland—his mother is in the hospital, about to have surgery related to her ever-worsening diabetes. The Red Cross makes arrangements for Yogi to travel back to St. Louis; he arrives a day after the surgery and stays until Paulina is able to return to her home on The Hill. It’s hard to know who worries more about the well-being of the other, mother or son. Paulina sends Berra’s little sister Josie over to St. Ambrose Church every few days to pay $5 and light a candle in front of a statue of Jesus.

“She prays hard for that boy every day,” Josie tells her friends.

Berra returns to Bainbridge, then goes to the expeditionary base at Little Creek, eight miles down the road from Norfolk, to train for amphibious landings. He wonders why he doesn’t hear from Bodie, but mostly he wonders how to fill the hours when he’s not training. It’s a classic case of military hurry up and wait, and Berra spends most of his free time reading his comic books and going to the base movie theater at night. The only saving grace: he gets a good seat at the base movie house, his favorite spot, instead of battling the long lines in jam-packed Norfolk.

Yogi is enjoying Boom Town, starring Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy, when the screen goes blank, the lights go on, and all the enlisted men are instructed to report to their barracks. Their commanding officer has an important announcement. Minutes later, Yogi is standing at attention when his CO asks for volunteers for a secret mission—manning new “rocket boats” that will surprise the Nazis in the long-awaited invasion in Europe. Yogi’s hand shoots up instantly.

“I want to join,” Berra says. The rocket boats sound exciting. Bodie and baseball have disappeared from life, and this new assignment would mean the end of the mind-numbing boredom. “All this hangin’ around is driving me crazy,” he tells a fellow seaman. “I just hate it.”

Berra is shipped out to a base just below Baltimore, where he’s told more about his mission. He’s there to learn about a speedy 36-foot wooden-hulled flat-bottom boat called a Landing Craft Small Support—LCSS, in naval parlance. About half the ship is covered by a steel deck—the only cover for the crew of five seamen and one officer. Three machine guns on ball turrets are mounted on the deck, and there are two rocket launchers, each holding 12 rockets, bolted to each side of the boat’s stern. Yogi is assigned to the twin 50-caliber machine guns and tasked with loading the rocket launchers as fast as he can.

The seamen are instructed to talk to no one—not family, not girlfriends, not anyone!—about their mission. Just to make sure, the Navy censors all mail leaving the base. Berra doesn’t mind, he tells his new shipmates. Working on a top-secret mission means you’re important.

But it also means you’re expendable. The rocket boats will be the leading edge of the massive D-Day invasion, setting up 300 yards from the beach. Their job: lob rockets into embankments along the shore to draw the fire of Nazi machine-gun nests so Allied warplanes can take them out, clearing the way for ground forces arriving in hundreds of transport ships. “We’re cannon fodder,” Berra jokes with a nervous laugh. The seamen come up with a new name for their LCSS: Landing Craft Suicide Squad.

Berra and his team train hard for five weeks, then leave to join a convoy in Halifax, Nova Scotia, for the 20-day journey to England. Berra is aboard the USS Buckley, a destroyer escort that is little more than a giant scooped-out hull topped by a steel deck. Eight rocket boats are loaded into the hold along with their crews, who are housed in bunks stacked four high along the walls.

Berra thinks of all the tales his father told of his tough voyage from the old country to America in steerage—the belly of the boat—but Yogi is sure those were luxury accommodations compared to this flat-bottom ship that sways from side to side even in calm seas. One sailor or another is vomiting at all hours. Even when Yogi doesn’t feel sick he’ll go topside to escape the stench.

Sleep on this voyage is all but nonexistent. There’s the constant “Now hear this: clean sweep down fore and aft” blaring over the loudspeakers. Worse is the near-regular beep-beep-beep of the general quarters alarm, which every sailor responds to at full speed. After spending so much time staring at the walls down below, imagining a torpedo tearing through and all that water rushing in to drown them, Yogi and every other sailor jumps when they hear that alarm, never questioning if it’s a training exercise or the real thing.

The convoy loses two of its 74 ships to German U-boat torpedoes: Berra and his crew arrive safely in Glasgow in early May, and the entire unit is soon on a train to Portsmouth in southern England, where they join more than two million men who have amassed for the invasion of Normandy. Yogi’s never seen so many military men in one place. No one has. Operation Overlord, the code name for the invasion of Normandy’s five beaches along a 50-mile stretch of France’s coastline, will be the largest amphibious military strike in history. Almost 5,000 ships will cross the English Channel, including scores of transport ships carrying more than 150,000 ground troops. More than 1,000 aircraft will provide cover.

Berra and his shipmates train intensely for days, spending hours at the firing range, hours more on physical conditioning. Ground troops practice exiting transport ships and crawling under barbed wire with live fire passing overhead. Army Rangers practice scaling cliffs while paratroopers make jumps day and night.

Everyone is on edge when word finally comes: the invasion, almost a year in planning, is set for June 5. Berra and his team climb into their LCSS on board the USS Bayfield the night of June 4. At 5 a.m., bad weather convinces General Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe, to postpone the invasion one day. Berra and his mates remain aboard their boat for the next 24 hours, cramped and tense, endlessly reviewing their instructions. There will be no sleep this night.

“Now hear this, now hear this,” a voice blares over loudspeakers at 4:15 a.m. on D-Day. The next words come from Eisenhower. “You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months,” he tells the Allied troops. “The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you.”

It is still dark when 20,000 men parachute behind enemy lines. Their mission: take out bridges and seize control of the roads to cut off escape routes and prevent Nazi reinforcements from entering the battle zone.

At precisely 5 a.m., Berra’s rocket boat is lowered over the side of the Bayfield and into the French side of the English Channel, where they rendezvous with 11 other rocket boats and race off to Utah Beach. A dozen more rocket boats are heading to Omaha Beach; battleships, destroyers, and transport ships follow close behind. There are so many ships in the water that one pilot flying cover overhead will later say it appeared as if he could walk across the channel stepping from one boat to another.

The assault starts at Utah Beach. Berra loads one rocket after another into his boat’s launcher, each one searching for Nazi machine gun nests. One connects, and after an onslaught of rockets lets loose from all 12 boats, the Germans return fire. Everyone on Berra’s boat is ordered below, but Yogi can’t resist poking his head above deck.

He almost can’t comprehend what he sees. Shells from warships are soaring overhead and exploding up and down the beach. The air is thick with Allied warplanes, which meet almost no resistance from Luftwaffe aircraft and are firing on dozens of Nazi positions. One ship gets too close to a German mine and is flipped right out of the water. All the flashing lights and thunder of guns give Berra a sense of Fourth of July fireworks gone out of control.

“Get your damn head down,” Yogi hears his officer shout over the explosions, “before you get it shot off.”

Small transport ships rush by and pull right onto the sand at 6:30 a.m., unloading wave after wave of American GIs. Utah will suffer the fewest casualties of all five beaches, but 197 of the 21,000 men who storm this beach will never see their loved ones again. Soon enough it will be the rocket-boat crews who scoop the wounded and the dead out of the water here and at Omaha Beach and bring them back to the Bayfield.

The Allies secure their first beachhead at Utah, with British and Canadian forces securing beaches code-named Gold, Juno, and Sword next. Allied forces face the heaviest resistance at Omaha Beach. Transports cannot quite reach this beach, so soldiers—those not killed by enemy fire the moment the doors of their transports drop—wade through water, at some points shoulder high, and go ashore. GIs drive jeeps submerged underwater by sitting atop seat backs, their heads barely above the sea.

Tanks that are supposed to provide support are let out in water that is too deep and sink instead. The sand is heavily fortified with mines, barbed wire, and trenches, and German guns are positioned on hard-to-reach bluffs high above the beach. It’s not until nightfall that American forces gain control at Omaha Beach, but the cost is high: Berra and his shipmates soon learn that almost 3,000 men have lost their lives. In all, 4,500 Allied men die in this assault, with at least as many injured. More troops arrive the next day; the fighting in Normandy will continue for months, but the Nazis are clearly on the run. No one knows it at this moment, but Hitler, slowly realizing all is lost, will shoot himself in a bunker the following April 30. The Germans will surrender the next week.

Hitler’s Luftwaffe has been all but absent, but Berra’s crew is instructed to shoot every enemy plane it sees, and when an aircraft finally breaks through the clouds, Yogi and his mates open fire and bring it down. There’s just one problem: it’s an Allied plane. They speed over to pluck the pilot from the water and find him both unharmed and livid.

“If you sonsabitches shot down as many German planes as you do ours,” he screams, “the war would have been over long ago!”

A storm hits on the third day, and Berra’s boat flips over in the rough seas; all the men are rescued and taken back to the Bayfield. There they remain, working almost nonstop the next 10 days, shuttling messages between Utah and Omaha Beaches, checking for mines, carefully escorting ships through the channel. On the 13th day the crews of the rocket boats are told to stand down, but no sooner does an exhausted Berra slide into his bunk than the general quarters alarm sounds.

“The hell with it,” Yogi says to a shipmate. “It if hits, it hits. I ain’t moving.”

A bomb does drop toward the stern of the Bayfield, but does little damage. Yogi knows he’s been lucky—today and every day during this critical mission. The things he’s seen—the men killed, others who leave the beach without an arm or a leg or worse—will stay buried in his mind the rest of his life.

***

Yogi sees action again when the Allies take Marseilles in the south of France in late August of 1944. The rocket boats are tasked with taking out a big hotel overlooking the Mediterranean Sea that serves as a Nazi command post. It’s protected by soldiers armed with machine guns and mortars, but the Allies fire one rocket after another, smashing giant holes in the stately structure. A bullet nicks Yogi in his left hand. It won’t affect his ability to play ball, and he won’t put in for a Purple Heart until he returns home—he doesn’t want to worry his mother.

Berra is one of many manning machine guns, cutting down the Nazis as they flee the burning building. It’s hard to know who kills each German soldier as the men rush to escape; it’s knowledge no one is eager to have. When the fighting is done, Berra and his shipmates go ashore, where they’re greeted by villagers who seemingly come out of nowhere, all carrying flowers and wine, smiling, cheering, and singing. It’s good to see this side of life after all the dying Berra just witnessed.

His next port is Naples, where his entire squadron—40 enlisted men, eight officers—takes up residence in an old inn on a hill overlooking the Bay of Naples. It amounts to an extended leave. Weeks go by without orders, so Yogi tours in the country of his parents, exploring Naples and the island of Capri, discovering his dialect of Italian isn’t spoken anywhere in southern Italy. He bumps into a friend from the neighborhood, Bob Cocaterra, who’s driving an Army jeep on his way to Milan.

“Can you take me to Rome?” says Berra, whose commanding officer tells him he can leave, but it’s his neck if their boat leaves before he returns. Yogi would love to visit Milan and the surrounding villages where he has family, but the Allies are still fighting German forces in northern Italy.

Besides, how often do you get a chance to see Vatican City and St. Peter’s Basilica? Yogi reaches Rome and wanders the city, even seeing the Pope on the balcony one day; he knows instantly how happy this will make his mother. He has no need for money; Americans are so welcome that chocolate and a few cigarettes pay for just about anything.

Berra is back in time for the squadron’s trip to North Africa, where he spends Christmas of 1944 in the historic Algerian port city of Oran, which dates back to 900 AD. There’s a depressing rumor they’ll be shipped out to the South Pacific to fight the Japanese, but news comes right before year’s end that they’re all going back to the States. Champagne corks are popped aboard the transport on New Year’s Eve as they begin 1945 with the three-week voyage home. When he reaches Norfolk, Yogi stays just long enough to get a train ticket for a monthlong leave in St. Louis.

Paulina loses her fight to hold back tears when her youngest son walks through the door, and the family feast begins almost immediately. Plates full of ravioli, lasagna, spaghetti, stufato—and, of course, bread and salad—never run out. Lawdie—it’s never Yogi at home—tells his parents all about the Pope and Vatican City, but very little about the carnage he saw. He shows off the medals and ribbons he’s won: two battle stars, a European Theater of Operations ribbon, a Distinguished Unit Citation, and a Good Conduct Medal. The Purple Heart, which he put in for once he was back—and safe—in the States, will arrive soon.

Berra returns to Norfolk and is hit with a blizzard of questions and paperwork. He meets with a Navy psychologist several times, each session centering on the same question: was he afraid out there in combat? No, Yogi keeps saying, there was no time to be scared, but deep down, he knows just how frightened he really was. Now that he’s back, he tells the psychologist, the feeling of dread about what he lived through sometimes seeps into his mind.

Another doctor pushes and probes, checking his reflexes. All is well, and he’s told to write down what he wants to do next on the many forms he’s ordered to fill out. Sports and recreation, he writes over and over again.

Berra soon learns he’s been assigned to the submarine base in New London, Connecticut. Subs? Going into combat was bad enough; squeezing into a submarine and going below the surface is as bad as it gets. And didn’t you have to volunteer for subs?

But when he arrives at the New London base, he discovers he has it all wrong. The Navy actually granted his wish. His new job: sweep out the movie theater after each show and make sure no knuckleheads make trouble. Great! He’s not back in St. Louis yet, but his days in combat are over.

And best of all—the submarine base has a baseball team.

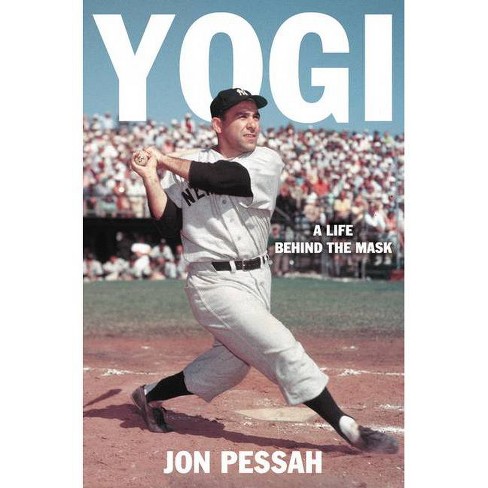

You can purchase YOGI wherever books are sold.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now