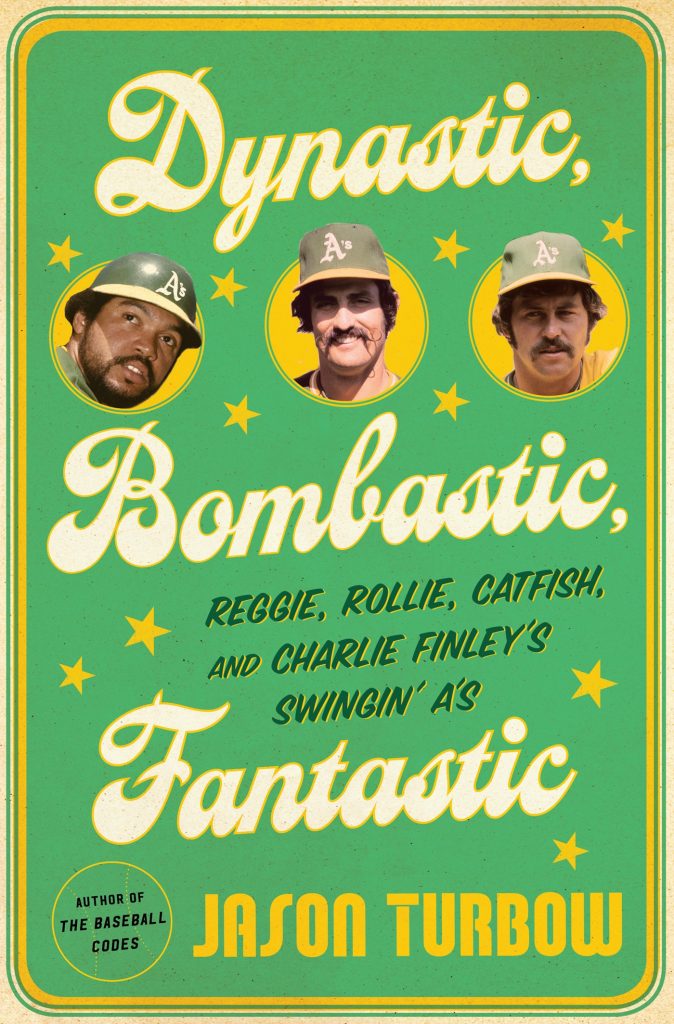

Editor’s Note: In light of the Athletics’ recent announcement regarding the status of their stadium deal in Oakland, and their interest in speaking with other cities about a potential move, the history of how the team arrived in Oakland is all the more relevant. As such, Jason Turbow has provided us a passage from the rough cut of Dynastic, Bombastic, Fantastic: Reggie, Rollie, Catfish & Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s. Most of it, along with the rest of the section on the A’s Kansas City years, did not make the final edit. Follow Jason Turbow at baseballcodes.com, and on Twitter at @BaseballCodes.

Upon buying the A’s in 1960, Charles O. Finley spent eight years in varying states of outrage, accusation, and denial when it came to the people of Kansas City. The idea of skipping town was never far from mind, and it seemed like the vast majority of his professional efforts were spent furthering that goal.

In 1962, he turned down a lucrative two-year contract with Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company to sponsor team broadcasts, because he didn’t want to be tied down if he decided to move before the deal was up. (Later, he would use low broadcast revenues as a prime reason for absconding to Oakland.) So tenuous were Finley’s local ties that he was booted from the Kansas City Chamber of Commerce for not paying his dues. When he lobbied Kansas City for funding for a new, 50,000-seat ballpark, it was little wonder how quickly he was refused.

Some of Finley’s outrage was justified. When the Dallas Texans football team moved to Kansas City in 1963 and renamed themselves the Chiefs, the city council allocated hundreds of thousands of dollars to build them new facilities, and charged only a dollar per year for rent for their first three years. “My God,” said Finley in Life magazine, “our offices were so cold my employees had to wear stadium boots and sit on heating pads in the winter, and I was paying $120,000 rent for the privilege. How much rent do the Chiefs pay for the stadium? One … dollar … a … year.” (The A’s rent was actually between $59,030 and $71,818, depending upon the year in question.) Finley asked the city to waive his rent if attendance fell below 800,000 (a slam dunk by this point) and be reduced to $50,000 otherwise. He also wanted an escape clause introduced to his lease. His timing was exquisite; the outgoing city council was in its final days in office and—spurred by Mayor H. Roe Bartle—wanted to make a splash. Insuring the A’s presence in Kansas City was just the thing. It approved Finley’s sweetheart deal, calling for a seven-year extension by a 6-1 vote.

His appeasement didn’t last long. The incoming city council wanted better terms, and because it had expanded from nine to 13 members it concluded that the five votes which had once been sufficient to pass an item were no longer enough. Finley now needed seven votes, they said, which was one more than he had. The agreement was struck down, and Finley reeled. As the Dec. 31 expiration for the old contract approached, Finley littered the bargaining table with proposals. A four-year contract. A five-year contract. No escape clause. Instead of rent he’d pay a quarter of his concession income and 5 percent of ticket proceeds. (This worked out to about what he’d already been paying, but insured that the city would have a vested interest in drawing people to the ballpark. It was more than fair, he figured, in light of the Chiefs’ dollar-a-year deal.) When those ideas were shot down, one by one, Finley offered to ignore the more than $400,000 he felt was still owed to him for his outlay on stadium improvements. He offered a two-year option. Still, no good. Every counterproposal the city presented called for rent independent of attendance figures, and Finley flat-out refused.

So intense was the his indignation outrage that he arranged a shotgun deal to move to Louisville, which had a vacant minor league ballpark, Fairgrounds Stadium, whose previous tenants, the Triple-A Louisville Colonels, had folded the previous season upon the disbanding of the American Association. Finley flew to Louisville in a lather, and without a lick of due diligence signed a two-year pact. The only thing missing was approval from the American League, which quickly overruled him.

In January 1964, still with no contract in place, Kansas City evicted the A’s from their stadium offices, forcing Finley to set up shop in the garage of one of his scouts, Joe Bowman. (Finley actually grew angry when Bowman’s wife used the house telephone for personal calls.) If anything, the process hardened him, and his bluster grew. The A’s would not leave Kansas City—that much had been decreed by the league—yet Finley did his level best to maintain leverage. “Rather than yield on any point, I will rent a cow pasture and put up temporary stands for the team to use next year,” he proclaimed. “The A’s will play in Kansas City and that’s definite, but they won’t use the stadium unless they are given what I consider a fair lease.” This was Finley at his power-tweakingest best. He sent his right-hand man, Pat Friday, location scouting to area farms, and settled on a 320-acre pasture in the wondrously named Peculiar, Missouri (city motto: “Where the ‘odds’ are with you), upon which he could lavish some diversionary attention. He hired celebrity lawyer Louis Nizer—whose 1962 book “My Life in Court” spent 72 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list—and threatened an antitrust suit against his fellow owners.

The latter tactic proved to be popular in both sides of the fight. Missouri senator Stuart Symington, fed up with the charade, made his own antitrust threat—but unlike Finley, he was in a position to order a governmental examination of baseball’s exemption to fair-competition and restraint-of-trade laws. If Finley hadn’t already managed to coalesce baseball’s ownership circle against him, this did the trick. League owners came to the opinion that Kansas City had bargained in good faith and put a reasonable lease proposition on the table, and ruled 9-1 (the one vote, as always, being Finley’s own) to inform him that he wouldn’t be around much longer if he didn’t bring the entire mess to a conclusion that was suitable for everybody. Chastened, Finley signed a four-year lease in Kansas City. In return for his cooperation he was granted permission by the league to explore Dallas and Oakland as possible destinations—a concession that was not binding, but would serve the purpose of shutting him up for a while.

Still, the rumors never slowed. Finley approached Milwaukee and Atlanta. He inquired about sharing San Francisco’s Candlestick Park while a stadium was constructed across the bay, and was shot down by Giants owner Horace Stoneham. “I have confidence in the future of the Kansas City A’s,” he insisted, adding the not inconsequential caveat, “If not in Kansas City, then somewhere else.” Fans, already soured on Finley’s deceit, doubled down on their apathy. Attendance shrunk from 642,478 in 1964 to 528,344 in 1965, despite a two-win improvement on the field. Season tickets dropped by nearly half over Finley’s first three years of ownership, to just 2,039. He claimed losses of anywhere between $200,000 and $600,000, depending upon how angry he was when he was talking.

***

Finley had arranged exploratory meetings in Oakland as far back as 1962, but the area’s primary attraction for him—the multipurpose Coliseum/Arena complex—did not open until 1966. He claimed to have lost $4.6 million on the A’s between 1964 and 1967—a number which, if anywhere close to accurate, had been inflated by Finley’s own partly-intentional souring of the community.

Things came to a head in In May 1967, when the New York Times and the New York Daily News both reported on Finley’s interest in Oakland. A new Kansas City ballpark was in his sights—the proposed Truman Sports Complex, with stadium plans for both baseball and football, was polling well and cruising toward approval—but he no longer cared. Finley wanted out and had long since stopped trying to hide it. Even as rumors swirled that he would move the team to Milwaukee (where city officials offered him a sweetheart lease on Milwaukee County Stadium and lined up a sponsorship deal with Schlitz Brewing Company), Finley still needed league approval to leave Missouri. With his other prime target, New Orleans, off the map until the Superdome opened in 1972, Finley’s primary targets were Oakland and Seattle. At the recommendation of the Commissioner’s office, Finley hired as his lawyer the future United States Supreme Court Justice, John Paul Stevens, who was seen as capable and reasonable, and, it was hoped, would lend some stability to Finley’s frenetic search for a new home.

Finley traveled to Oakland in 1966 to assess construction progress on the 50,000-seat Coliseum, and returned later in the year for the first-ever Raiders game there. The more he saw of the East Bay, the more he liked it. That October, Finley’s four-year lease extension on Municipal Stadium expired, and American League owners met in Chicago to decide what to do with the guy. He had been agitating to move nearly since he bought the A’s, and now, with four months until spring training, his demands for moving to Oakland reached a crescendo. Seven votes were necessary to approve a move; Finley had five. Baltimore opposed him, while Cleveland, New York and Washington abstained. American League president Joe Cronin did not want what was certain to be many years of Finley-vs.-Kansas City if the guy was forced to re-up in a city that held no interest for him. He called for a re-vote, and the Yankees decided to approve the move. At long last, Finley had his freedom.

As a measure of conciliation to Missouri, the owners voted to place an expansion team in Kansas City the very next season, 1969. Ownership of the new franchise would be decided by the following May, and stadium construction could proceed apace. Because the arrangement would give the American League 11 teams—an unwieldy total—they decided to add another team as well, and split into two divisions. That team ended up being the Seattle Pilots, and so rushed was their creation that they would stay in Seattle for only a single season, losing 98 games and drawing fewer than 700,000 fans before taking off for Milwaukee. (Pressed to follow suit, the National League added teams in Montreal and San Diego on the same timeframe, and also split into divisions.) Thanks in part to Charlie Finley, teams heretofore would no longer be fighting for the pennant during the regular season, but for a playoff berth against their opposing divisional champion.

Missouri senator Stuart Simington, a longtime Finley foe, called Oakland “the luckiest city since Hiroshima.”

***

Finley had so set his mind on Oakland—perhaps with the idea of bucking every owner who told him that a two-team market in the Bay Area would never work, despite the obvious logic in that conclusion—that he’d all but ignored the abundance in Seattle. He loved Oakland’s ballpark, he said, and its climate (“very ideal for baseball”) and its population growth. On more than one of these items he was mistaken. Finley hired a firm to research the pros and cons of both Oakland and Seattle, then ordered it to “tell me to move to Oakland.”

Finley got straight to negotiating with the city, agreed on loose parameters, moved his headquarters to the Coliseum and started selling tickets for the 1968 season. Remarkably, he hadn’t yet signed a contract. This was Finley’s way: Keep things as nebulous as possible while continuously trying to shift bargaining power into his own camp. Squatting on a property, after all, builds more leverage than pleading from afar. The Coliseum Commission finally forced Finley’s hand by presenting a deal that would be enacted in lieu of a lease agreement: day-to-day rental at about double the cost, and minus his percentage of parking and concession revenue. Still Finley continued to haggle, straight through the winter. Prior to one meeting he told Stevens that if the commission didn’t give them what he wanted they would storm out in a staged display of anger. What he forgot to consider was that an empty Coliseum wasn’t exactly a hotbed of transportation options. With no car of their own and no public transportation nearby, Finley was forced to sheepishly return to the meeting room and ask for a ride back to his hotel.

Eventually Stevens—Finley’s own lawyer—grew fed up with the protracted act and, as they examined the latest contract revisions which Finley was preparing to dissect and skewer, took a pen from his pocket, put it in Finley’s hand and said, “Sign.” Finley did. With only weeks left until the start of the season, the deal was done.

Finley ended up with guaranteed broadcast revenue of more $1.1 million per season from the Atlantic Richfield Company for the first five years of the contract, plus 25 percent of the concessions, 27 ½ percent of parking and an almost negligible rent of $125,000 per year. With a payroll just north of $200,000, Finley had secured a hefty return on his investment—but not enough of one to keep him out of his new landlord’s hair. In addition to paying rent, the Coliseum deal put Finley on the hook for ballpark maintenance and cleanup, as well as a share of general overhead. This meant that he had considerable checks to cut to the Coliseum Commission each month. Finley began disputing the expenses nearly from the get-go, things like staffing positions for ushers and ticket takers. Because there was a dispute, he didn’t pay. And when he didn’t pay, the Coliseum commission had to return to the table.

The Coliseum was working with standard labor rates and staffing patterns, they said, which wasn’t good enough for Finley, whose delinquent payments quickly climbed toward $200,000. This was standard procedure for him, withholding payments as long as possible to maximize interest while the money was still in his own accounts. The Coliseum finally took Finley to arbitration, where a supplemental agreement was inserted into the contract stipulating that in any month in which he was overdue on payments he would receive no revenue from parking or concessions. Just like that, bills began being paid on time.

Finley finally signed a 20-year lease agreement at the Coliseum, with four additional five-year options. He would later claim that it was he himself who insisted on the duration, at the signing itself. Pen in hand, Finley grandiosely announced, “You know, this contract is for 10 years. I like this area so well, and the terms of this contract so much, that I want to change it to a minimum of 20 years right now.” Then he did. At least that’s what Finley told New York Daily News columnist Dick Young a decade later. Finley said a lot of things.

At the welcoming luncheon for him in Oakland, Finley said the A’s would forever have the city’s name across their shirts as a symbol of his pride. That lasted one year, “Oakland” replaced in 1969 by the letter A. Finley’s proclamations to be in the East Bay for good held similarly little water. “I bought the team in Kansas City,” he said. “I have brought it to Oakland. There is a difference. I took the only team I could get. I had no choice over where it was. Bringing it to Oakland was my choice. Once I make a decision, I stand by it, I give my word of that. I will move to Oakland. I will move my family to Oakland. I will keep my team in Oakland. And the A’s will succeed here.”

Finley did not move to Oakland, nor did his family. He showed up a few times a year to watch the A’s play, and caught them in Chicago and occasionally in Milwaukee. But when it came to the promise that the A’s would succeed … well, Finley was right about that one.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now