This series of articles is based on a presentation at the 2021 SABR Virtual Analytics Conference on March 11-14. You can watch the presentation, listen to it, view the slides, and see all the presentations at the conference. You can register for the 2022 conference here.

In Game 5 of the World Series, Jose Urquidy faced A.J. Minter in the bottom of the fourth with one out and a runner on first. Minter squared to bunt Urquidy’s 92 mph fastball. Instead, he popped the ball up in foul territory. Martín Maldonado caught it for the second out of the inning.

That weak popup may be the last plate appearance out of the pitcher’s spot in the linuep in MLB history (non-Ohtani division). In this series, I’m going to look at the history of the designated hitter, the National League’s experience with the universal DH in 2020, and what the future might hold for pitchers batting for themselves.

In 2020, it’s said, we all became amateur epidemiologists and immunologists. We also, thanks to modern science, got a crash course in clinical trials. Clinical trials are randomized controlled studies in which a broad selection of randomly chosen patients, representing a representative sample of a broad population, are split among participants who receive a treatment vs. participants who do not. The researchers go to great pains to ensure that they have selected study participants carefully. Clinical trials yielded the COVID-19 vaccines that are going into people’s arms.

Natural experiments, by contrast, don’t use a controlled population. Sometimes, they are population-wide. In 2007, Sri Lanka banned certain pesticides. Researchers found that following the ban, suicide rates fell, providing a link between banned pesticides and suicide. Sometimes, they occur when there is a naturally-occurring split in populations. We can measure the effects of poverty on health outcomes by comparing impoverished people to more well-off ones without randomly assigning people to poverty or not. Instead, researchers have found, e.g., that poor people who escape poverty are healthier than those who do not, illustrating both that poverty affects health and that the relationship is causal; i.e., it’s not simply a case of poor health causing poverty.

While controlled experiments like clinical trials will remain the gold standard for scientific endeavors such as vaccine development, natural experiments are valuable as well.

***

In 1972, American League teams hit .239/.306/.343. Teams scored 3.47 runs per game, the fourth lowest in league history. In an era before regional sports networks and huge national TV contracts, attendance was falling. After a peak of 11,336,923 in 1967—1,133,692 per team—attendance per club had fallen for five straight years, despite 1969’s expansion, to only 953,212 in 1972. In 1967, only three teams drew fewer than 950,000. In 1972, eight did.

In January 1973, seeking to inject more offense into the game and, therefore, it was hoped, boost attendance, MLB voted to adopt a “designated pinch hitter” in the Junior Circuit. This was most assuredly not a natural experiment. Clubs had months to prepare for the new role of a full-time hitter who would bat in place of the pitcher. Several adjusted their rosters.

- October 1972: Texas traded with Atlanta for 33-year-old Rico Carty

- November 1972: California traded with Los Angeles for 37-year-old Frank Robinson

- January 1973: Boston signed free agent 35-year-old Orlando Cepeda

- April 1973: Yankees purchased 31-year-old Jim Ray Hart from San Francisco

- May 1973: Oakland traded with Philadelphia for 34-year-old Deron Johnson

Even if you don’t give the Rangers and Angels points for prescience, the trend is clear. There was a migration of aging sluggers from the National League to the American League in preparation for the inaugural DH. In addition, American League veterans like 31-year-old Alex Johnson, 34-year-old Tony Oliva, 34-year-old Tommy Davis, and 34-year-old Gates Brown saw expanded roles over their 1972 playing time. For 36-year-old Frank Howard, the DH may have tacked an extra year onto his career, as in 1972, he’d set career lows for games, average, slugging, homers, and isolated slugging. He and Brown were Detroit’s platoon DHs in 1973.

The hand-the-bat-to-the-old-guy approach wasn’t a rousing success. DHs were seventh in the league in batting average, sixth in on-base percentage, and fifth in slugging percentage in 1973 among the nine positions on the field. Their .720 OPS was sixth overall, ahead of only catchers, second basemen, and shortstops. Their .257/.328/.393 line easily exceeded the .145/.184/.182 posted by pitchers in 1972, of course, but it was less than expected.

In the ensuing 47 years, DH strategies have evolved. Nine players (David Ortiz, Harold Baines, Edgar Martinez, Hal McRae, Frank Thomas, Don Baylor, Paul Molitor, Chili Davis, and Travis Hafner) have appeared in over 1,000 games as DHs. None was older than 30 the first season in which he appeared primarily as a DH. Some were DHs due to defensive limitations, some to preserve their health. Four are already in the Hall of Fame, and Ortiz is a safe bet to join them.

Teams’ DH strategies have changed with their personnel. In 2002, the year before Ortiz arrived in Boston, the Red Sox didn’t have a settled DH. Five Red Sox batters accumulated 98-223 plate appearances at DH. Since his last season in 2016, though, the team’s gone with a full-time DH, first Hanley Ramírez and then J.D. Martinez. By contrast, the Yankees have mostly rotated the position. From 2004 to 2016, Ortiz appeared at DH at least 100 times except in 2012, when he was hurt During those 13 seasons, only Hideki Matsui in 2009 and Alex Rodriguez in 2015 appeared in 100 games at DH. The only American League team with fewer seasons with a DH appearing in 100 games was the Twins, apparently still being punished for letting Ortiz go.

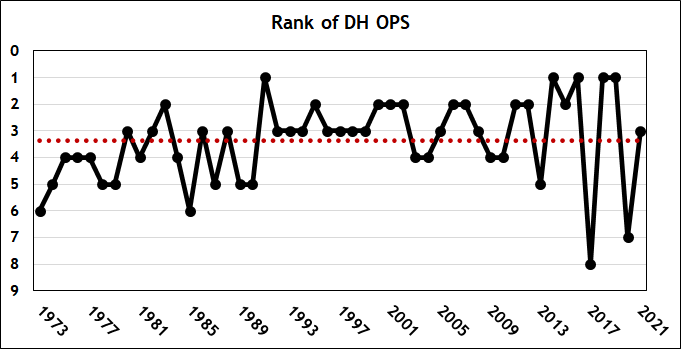

Over the subsequent years, American League DHs have improved from 1973’s level, with a few hiccups along the way. On average, DHs’ OPS has ranked about third among the nine positions in the lineup, as the dotted red line indicates.

(If you were wondering: In 2017, when DHs were worse than everybody but catchers, Albert Pujols hit .242/.286/.391 in 611 DH plate appearances, Mark Trumbo hit .207/.268/.367 in 467, and Carlos Beltrán, presumably focused on other pursuits, hit .228/.279/.391 in 412.)

An unsurprising pattern has emerged: The teams with the most success at DH have employed an outstanding hitter in a more-or-less fulltime role. Here are the teams with the highest DH OPS over the past dozen years. Plate appearances (PA) and OPS are as a DH.

| Year | Team | Primary DH | PA | OPS |

| 2021 | Los Angeles | Shohei Ohtani | 560 | .981 |

| 2020 | Minnesota | Nelson Cruz | 213 | .997 |

| 2019 | Minnesota | Cruz | 515 | 1.028 |

| 2018 | Boston | J.D. Martinez | 400 | .970 |

| 2017 | Seattle | Cruz | 645 | .933 |

| 2016 | Boston | Ortiz | 613 | 1.033 |

| 2015 | Toronto | Edwin Encarnación | 370 | .993 |

| 2014 | Detroit | Victor Martinez | 494 | .973 |

| 2013 | Boston | Ortiz | 575 | .964 |

| 2012 | New York | Alex Rodriguez | 170 | .837 |

| 2011 | Boston | Ortiz | 590 | .964 |

| 2010 | Boston | Ortiz | 584 | .908 |

Looking at that table, one would conclude that having a talented full-time DH is the key to success at the position. Only two teams—the 2015 Blue Jays and the 2012 Yankees—managed to lead the league at DH OPS without a single player accounting for at least 400 plate appearances at the position.

In 2020, though, National League teams didn’t have time to build an Ortiz into their rosters. The universal DH wasn’t adopted until a few weeks before the season began. The league’s DH natural experiment began last July.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

It will be a series, I think of four articles total (Rob can clarify). So there will be more...next week!