This article was originally published on September 9.

In the first part of this series, I illustrated that starting pitchers are pitching less frequently—on more days of rest—than ever before. In the second part, I noted that innings per start, whether measured by length of average outing or percentage of starts lasting at least five innings, are also at all-time lows. In the third part, after considering several potential explanations, I concluded that this was likely by design, and even if the pandemic has exacerbated some of these usage trends, the trends are nonetheless intact.

To put a bow on this examination: What does it mean?

Certainly, the role of MLB starting pitchers is changing. Just ten years ago, 12 pitchers threw at least 225 innings. No pitcher has matched that workload since 2016. Only Zack Wheeler, Walker Buehler, Sandy Alcantara and Adam Wainwright are on pace for 200 this year through Tuesday’s games, a mark 39 pitchers eclipsed in 2011.

Of course, the role of players has changed throughout baseball history. In the 30 seasons from 1904 to 1933, second basemen outhit third basemen (using FanGraphs’ wRC+) in all but six seasons. That seems weird to us today. It hasn’t happened in the nearly 90 years since 1933. But for a long time, third base was a glove-first position for nimble fielders who could handle a deluge of bunts. Second basemen weren’t valued for their skills on the pivot in an era where double plays were rare.

Similarly, the mental image of a shortstop as a slight, lithe, acrobatic fielder progressed from Luis Aparacio (5-foot-9, 160 pounds) to Mark Belanger (6-foot-1, 170) to Ozzie Smith (5-foot-11, 150). Today, aided by shifts, larger guys like Carlos Correa (6-foot-4, 220), Corey Seager (6-foot-4, 215), Fernando Tatis Jr. (6-foot-3, 217), and Xander Bogaerts (6-foot-2, 218) make All-Star teams and sit atop offensive leaderboards, since the importance of infielders’ range is diminished if you’re positioned where the ball gets hit.

But in these cases, there was a value exchange. As the Deadball Era progressed through the Lively Ball Era, third basemen traded in defense for offense. Second basemen did the opposite. Shifts are enabling a swap among middle infielders similar to that of third basemen a century ago. Glove gets traded for bat or bat gets traded for glove. It’s sort of like the first law of thermodynamics applied to position players. The value of third basemen, second basemen, and shortstops is maintained. How they derive that value changes.

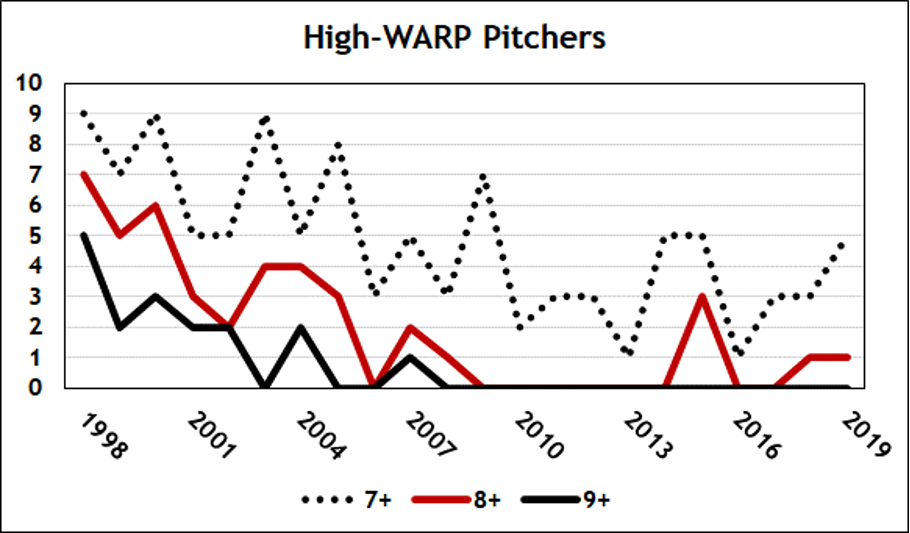

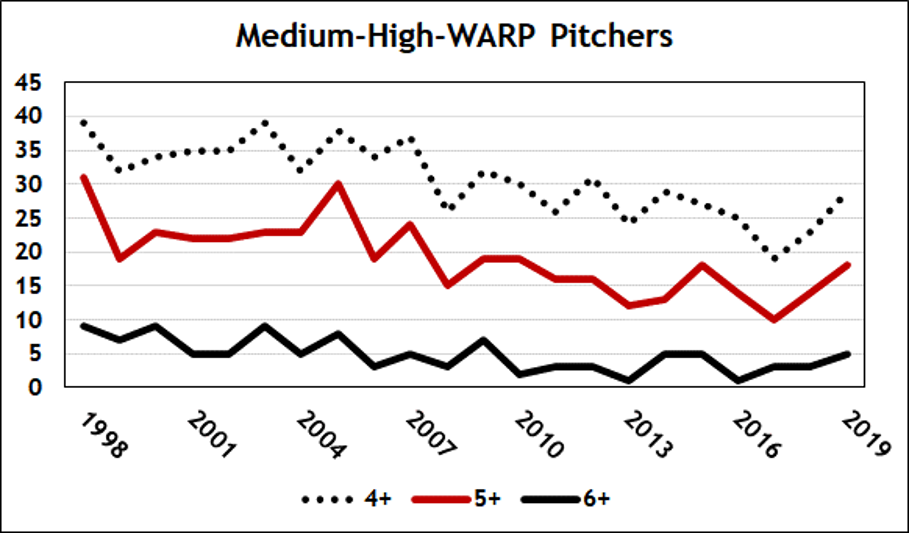

This isn’t happening with starting pitchers. By taking the ball less frequently, and not pitching as deeply into games, they are relinquishing value. In 1998, the first year of the 30-team era, three pitchers (Kevin Brown, Curt Schilling, and Randy Johnson) accumulated over 10.0 WARP. Over the last four full seasons, only two pitchers (2018 Jacob deGrom, 2019 Stephen Strasburg) have earned even 8.0 WARP. High-WARP starting pitchers have steadily declined over the 30-team era.

That value isn’t being transferred to starters in the next-highest threshold. They’re in decline as well.

So far in 2021, the number of high-WARP pitchers has cratered. Nobody’s close to seven or more WARP; that’s unprecedented in a full season. Wheeler is on pace for 6.0. He, Corbin Burnes, and Brandon Woodruff are on pace for at least five. Another eight are on pace for at least four. And that’s it. Eleven four-WARP pitchers, compared to a previous low of 19.

Where is the value going? It’s being split among the eight or nine relievers in contemporary bullpens. It’s not going to particular pitchers; the last reliever to get 4.0 WARP was Brad Lidge in 2004. The value being lost by starters isn’t going to any individual relievers; it’s going to the amorphous blob comprising a bunch of one-inning relievers, many of whom spend the season shuttling between AAA and the majors.

That doesn’t mean pitching is less valuable. It’s the allocation of that value that’s shifted. Back at the start of the Divisional Play Era, pitching value resided primarily with five starters, with some residual going to teams’ four or five relievers. Since then, the value held by starters has declined, and the reliever corps to which it’s gone has grown. So while the value of individual starters has eroded, the value of individual relievers hasn’t grown. Nobody’s become more valuable, and starters have become less so.

This has three repercussions. The first is gameplay. I don’t need to tell you that strikeouts are up and balls in play are down. We all know the times-through-the-order penalty is a real thing. As I’ve written, it’s worse than people think. But with starters taken out of games earlier, those third-time opportunities for hitters are going away. Instead of a tiring starter, batters are facing max-effort relievers, 15-20 pitches at a time. It’s hurting offense.

The second is compensation. If starters generate less value, one could argue that they warrant lower compensation. Those dollars should flow to relievers, maintaining overall payrolls. But they don’t. Many of the fungible pitchers in the bullpen are making the major league minimum. Many don’t even spend the full year on a major league roster. Their limited role prevents them from accumulating the totals that would warrant raises beyond the inflation factor built into the MLB minimum.

The third is career value. From 1981 to 2000, the BBWAA voted 18 position players and 12 starting pitchers into the Hall of Fame. Over the next two decades, that ratio swung to 28 position players and only 8 starting pitchers (9 if you count Dennis Eckersley). Granted, the Hall of Fame vote is an imperfect gauge of talent, but the decline of starting pitching is notable. Maybe it’s a reflection of writers still clinging to the old standards of 300-win careers and 20-win seasons. Of maybe it’s because the value starting pitchers, even the best ones, contribute to their teams is eroding.

A great hitter can’t provide as much to his team in 450 plate appearances as he can in 600. A great pitcher can’t provide as much to his team in 180 innings as he can in 240. The definition of the starting pitcher has shifted. Absent a significant change in baseball’s rules (I’m still a fan of limiting pitching staffs), that shift necessarily means that the role of starting pitchers and their contribution to teams’ success is diminishing.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now