This article was originally published on August 25.

The bat was out of Jazz Chisholm’s hands before Tucker Barnhart could even pull the 3-2 pitch into the strike zone; he was already reaching to unlock his shin guard when home plate umpire Jim Wolf raised his fists to punch him out. And as Chisholm sighed and spun away, Wade Miley had already turned his back, loping toward the rubber to kick away some stray dirt. There are times, watching Miley, when it feels like he’s forgotten that there’s a batter at all; if there’s effort in his delivery, a pulse of tension after his shuffling, toe-tap windup, it appears more like the strain of age, of a middle-aged man forcing himself out of an easy chair.

It’s often commented that baseball players, especially pitchers, frequently fail to look the part of world class athletes, but Miley is an exception even to that rule. Instead of making his craft look easy, he has a habit of making it look impossible. His pitches do not confuse the batter, even in the crafty, Bugs Bunny changeup sort of way; they do not dodge or die. Every single one should be driven into the seats. Every season, every start, every pitch should spell disaster. And yet it never does.

Four years ago I catalogued the hard times of Wade Miley, calling him “the strike zone exile.” Limping to one of the very worst seasons (-2.9 WARP) for one of the most disappointing teams (the era-ending 2017 Orioles) in the league, the southpaw appeared fairly cooked. If he threw pitches in the strike zone, they got pummeled. If he threw them out of the zone, batters held their bats back and watched. He didn’t have the kind of stuff to trick hitters into chasing them. So the only option he had was to throw the most attractive non-strikes he could, and hope the batters helped him out. It wasn’t a plan to inspire much confidence.

So of course in 400 innings from 2018-2021, he’s provided 8.7 WAR by the results-based Baseball Reference metric, and is contending for the 2021 NL Cy Young Award.

It’s not that simple, of course. By FIP-based WAR, that number drops from 8.7 to 6.2. And by BP’s DRA-based WARP, it plummets to 2.5. Miley doesn’t strike people out, he walks more than a crafty lefty ought to get away with, and he perpetually scrapes by thanks to those twin forces of impending regression: low HR/FB rates and low BABIP numbers. No one gets away with this sort of behavior. So why has Wade Miley, for four years running?

***

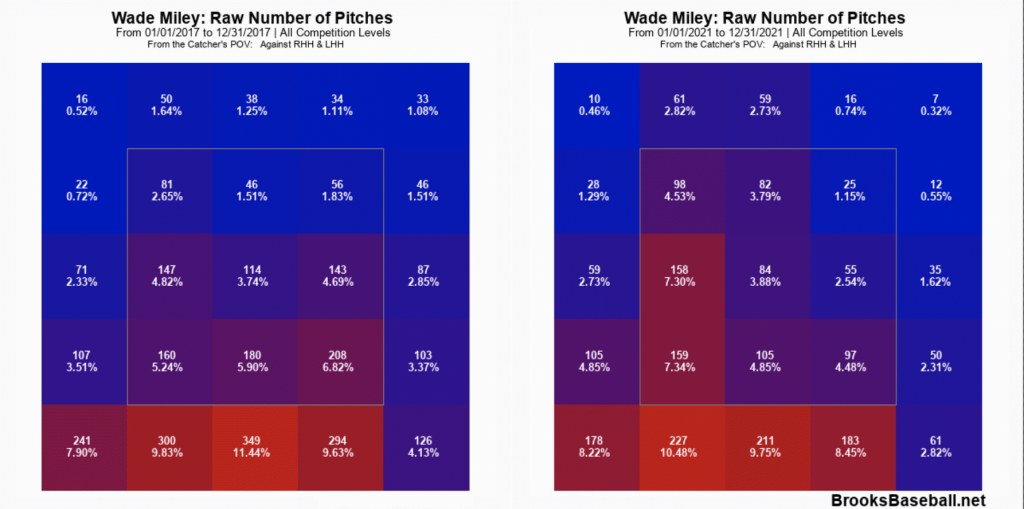

First, let’s go over what changed between the nadir of 2017 and the precipitous heights of 2021. The most obvious transformation was noted at the time: “It should be noted that Miley is a pitcher, so he could change his process tomorrow or discover Trevor Cahill’s curve or find two ticks on the fastball in the bullpen. (According to Brooks Baseball, Miley recently reintegrated a cutter to his menu of pitches, first tried out last year.)” Miley has essentially abandoned his slider and curve, which he could never quite target, and relegated his four-seam to a surprise third offering. His arsenal now boils down to two pitches: a cutter that shaves the outside edge of the plate, and a change that ducks out of the zone low and away. That’s it, repeated infinitum.

Miley has spent the past four years teamed up with solid, if not amazing, defensive catchers: Manny Piña in Milwaukee, Martín Maldonado in Houston, and now Barnhart in Cincinnati. Miley has the third-lowest rate of pitches thrown in the zone this year (37 percent), which makes it unsurprising that he easily leads the league in CSAA (Called Strikes above Average), with 0.23. For every four pitches he throws outside the strike zone that don’t get swung on, one gets called a strike anyway. That’s a powerful advantage to have, and a testament to Miley’s tightly controlled lack of control. The years have done nothing to erode his ability to throw the exact pitch he wants. But this was never the problem; the problem was that in 2017, it simply wasn’t enough. Without the ability to draw whiffs, and with hitters feasting on every strike like a meatball down the heart of the plate, Miley just had no path to getting reliable outs.

It turns out that he had one all along. We just didn’t realize how reliable it was.

***

When Wade Miley was a rookie a decade ago, the analytics community was still sorting out how independent defensive independent pitching statistics (DIPS) should be. We’re still refining that conclusion, but one thing that eventually became clear is that regardless of the defense behind him, a pitcher’s BABIP was not entirely out of his control. The leaderboard for BABIP in 2021 contains a multitude of All-Stars, Buehler and Scherzer and Woodruff and Gausman, as well as Mike Foltynewicz, because it’s easy to sport a low BABIP when every other hit you allow sails over the fence.

Through that conversation, BABIP has become an introductory concept for statistically-oriented fans, working its way onto all the major leaderboards, and yet its cousin, slugging percentage, has never made that same journey. It makes sense that pitchers who limit quality contact to the degree of suppressing batting average are likely to reduce extra bases on that contact as well, but the effect is largely left in the background. Looking at the leaderboard (250+ balls in play) for SLGCON (slugging on contact—in this case, we want to include home runs) provides an interesting list of names:

| Player | SLGCON |

| Kyle Gibson | .419 |

| Corbin Burnes | .424 |

| Framber Valdez | .425 |

| Walker Buehler | .429 |

| Brandon Woodruff | .429 |

| Charlie Morton | .443 |

| Cole Irvin | .443 |

| Wade Miley | .444 |

| John Gant | .446 |

| Cal Quantrill | .447 |

Again, this is a list of largely successful starting pitchers, plus John Gant, but some trends emerge. We’ve moved from “list of the greatest pitchers and one terrible one” to “list of the greatest groundball pitchers and one terrible one.” This makes sense—you’re not going to give up a ton of doubles on ground balls—but the equation has always been seen as the inferior side of a tradeoff, unless you’re like Burnes or Buehler and you strike out all the guys who don’t hit it into the ground.

And for many pitchers, it is. Mistake hitters exist because all pitchers make mistakes. One groundballer you don’t see on that list above, one who would be visible many other years, is Dallas Keuchel. Keuchel leads the league in groundball rate, but he’s also coughing up home runs on one out of every five fly balls, so that .273 BABIP isn’t providing his surface numbers much “luck.”

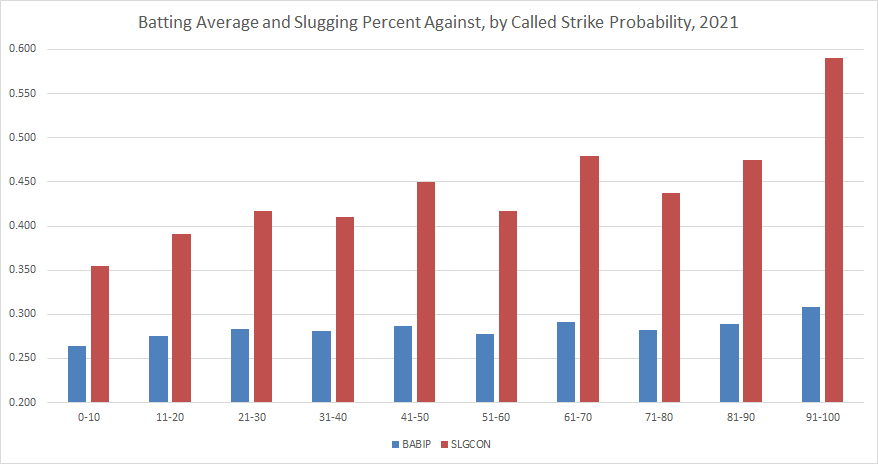

Miley makes mistakes, but he makes different ones. Instead of catching too much of the plate and risking a home run, he’ll err further away from the zone, and accept a walk. On three-ball counts in 2021, hitters are producing a slash line of .247/.529/.411 against him, demonstrating a complete refusal to compromise his approach when falling behind. He throws meatballs 3.6 percent of the time, half of the league average, and based on Baseball Savant’s broader “heart of the plate” attack zones, no starter wanders into it more rarely than Miley (19.3 percent). We tend to pay attention to grooved, meatball pitches, because they so often trigger highlights. But location acts as a gradient, not just for putting balls in play, but hitting them hard. Here’s a breakdown of how Called Strike Probability correlates with BABIP and SLGCON, for pitches in the bottom third of the zone:

So the math states that it’s not Miley at the losing end of a dominant strategy, forced to dodge the zone for fear of failure. It’s the hitters that are looking down the barrel: Either try to hit pitches they can’t really drive, or let them go and watch them get called strikes anyway. The numbers state that they should just not swing, and enjoy some favorable counts. Not that they do much good; since extra base hits are largely off the table, the offense has to put together three or four successful at bats at a time, all without putting one on the ground and wiping out the inning with a double play.

And that’s when the last piece of the puzzle comes in: tunneling. Miley’s pitches aren’t giffable. They’re not going to make fools of anyone. But they do break just late enough that they all look like mediocre strikes instead of mediocre balls. And really, the mediocrity just makes them all that more enticing, and more deadly.

As much as Matt Cain broke FIP in 2011, Miley is breaking DRA in 2021. Which is not really the negative it sounds like: if DRA believed in Wade Miley, it’d do a far worse job of evaluating everyone else. Because what Wade Miley is, and what he does, is not repeatable for other people. Miley trudges to the mound each inning like a kid heading to detention, and then sleepily performs a highwire act without a pole until he gets three outs. And then he does it again, and again. It can’t keep happening. It won’t keep happening. It’s fun as hell to watch as long as it does.

Thanks to Lucas Apostoleris for research assistance on this article.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now