This article was originally published on June 17.

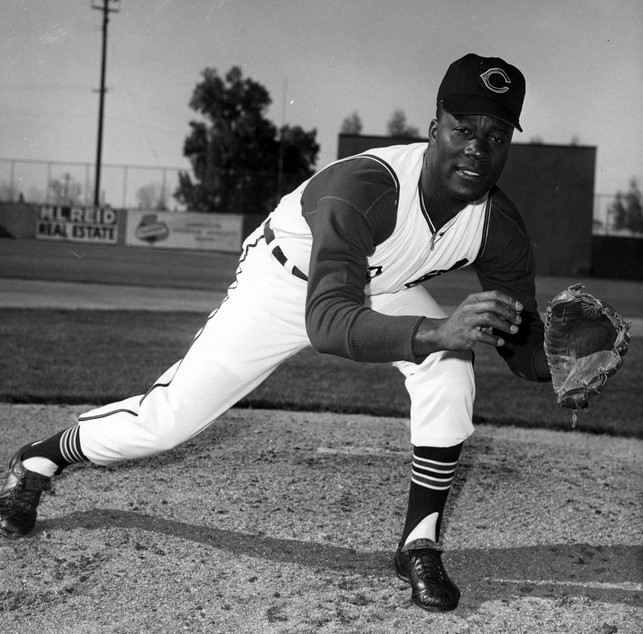

When James “Mudcat” Grant (1935-2021) passed away on June 11, one fact about his career stood as an indictment of the United States in the 20th century: In 1965, Grant became the first Black pitcher in the history of the American League to win 20 games in a season. The AL had claimed major league status for itself in 1901. In the ensuing 64 seasons, 129 pitchers won 20 games, 62 of them multiple times. None of them were Black. In the years between Larry Doby breaking the AL color line and Grant reaching the 20-win level the American League had 33 pitchers win at least 20 games in a season, a great many guys named “Bob” were given the opportunity to win 20—Bob Lemon, Bob Grim, Bob Porterfield, Bob Feller, Bob Turley—but players of color need not apply. “Opportunity” is the key word. Until 1958, when Grant was promoted to the majors and given 28 starts, no pitcher of color was given enough playing time to compile more than a handful of wins.

The story of the National League was a little different thanks to Branch Rickey and a more competitive environment. The senior circuit had 30 pitchers win 20 or more games in a season in 1947-1964 window and if Black and Afro-Latino pitchers still weren’t proportionately represented, at least they got their shot: Don Newcombe won 20 games three times during that span, Juan Marichal twice, and old Toothpick Sam Jones once. It’s not that no good Black pitchers were abroad in the land, but that the NL only wanted a few of them and the AL didn’t want them at all.

The absence of 20-game winners of color in the American League from 1901 through 1964 and the NL from 1876 through 1950 is a quintessential example of an almost passive racism that speaks quietly but is no less toxic in its effects. No doubt someone called Smokey Joe Williams the N-word at some time somewhere during his life, but no one in the established majors had to do so because the apartheid system that had been entrenched in the game and elsewhere (and enshrined in law via the Supreme Court’s 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision) meant that Williams never even got close enough to the field to hear an epithet.

This is a form of racism we are still arguing about in America today, one that comes out of structures rather than individual action. “Critical Race Theory” is a current cause celebre on the right as Republicans throughout the country have introduced laws to restrict its teaching, following the lead of the Trump administration, which last September instructed federal agencies to, “cease and desist from using taxpayer dollars to fund these divisive, un-American propaganda training sessions” in which “employees across the Executive branch” are “told that ‘virtually all White people contribute to racism’ or where they are required to say that they ‘benefit from racism.’” Pending further instruction these agencies were directed to identify all contracts or spending on “‘critical race theory,’ “white privilege,’ or any other training or propaganda that teaches or suggests either (1) that the United States is an inherently racist or evil country or (2) that race or ethnicity is inherently racist or evil.”

That’s not what Critical Race Theory is. It’s more complex than that, in part because (and this, one suspects, is part of its appeal as a target) like “Antifa” it isn’t an organized movement or codified set of doctrines. Rather, it’s a 40-year-old framework for analysis of social and legal conditions in the United States. As Marisa Iati wrote in the recent Washington Post primer on the subject, at its most basic level, “Critical race theory holds that race is a social construction upheld by legal systems and that racism is banal and common.” The New York Times recently defined it as a framework for intellectual inquiry that posits that, “historical patterns of racism are ingrained in law and other modern institutions, and that the legacies of slavery, segregation and Jim Crow still create an uneven playing field for Black people and other people of color.”

Just like the concept of replacement level in Sabermetric analysis, CRT is a method for establishing context. As with replacement level, when that revised context would seem to imply the need for new thinking, CRT causes consternation. Old school sportswriters resented having to give up their precious RBI as a measure of player quality. Old school nationalists resent the suggestion that racism is a key strain in American life and culture, even if one leaves chattel slavery out of the equation.

As with every human doctrine CRT can be extrapolated and twisted until one winds up somewhere far from its initial impetus, somewhere possibly less benign, and neither supporters nor detractors are exempt from that act of distortion. Some in the latter category reject that framework because of just such an extrapolation. As the Times put it, “Republicans accuse the left of trying to indoctrinate children with the belief that the United States is inherently wicked.” That is not CRT’s purpose nor its inevitable conclusion. Another reason to reject CRT is that it is about a civilization-wide effect, not an individual one, not racists, but racism. As Adam Serwer wrote in The Atlantic, “To accept that a problem exists is to accept the obligation to find a solution. And conservatives who don’t want to address America’s deep racial disparities are attempting to suppress any reading of history that suggests contemporary inequalities are the product of deliberate choice.” That is, to borrow from the gun-rights lobby, people don’t discriminate against people, policies discriminate against people. Actually, it’s both, but the point is to observe a distinction between levels of discrimination. When Cap Anson refused to play against Fleet Walker, he was one jerk being a racist. When organized baseball subsequently eliminated all players of color, that was systemic racism.

That shouldn’t be controversial. It’s clearly the case that racism and larger systems of American power have been intertwined starting from day one and continuing right down the line. Consider housing. As Richard Rothstein wrote in Color of Law, his recent book about how the local and state governments, as well as the federal government, structured housing along racist lines. “Until the last quarter of the twentieth century, racially explicit policies… defined where whites and African Americans should live. Today’s residential segregation in North, South, Midwest, and West is not the unintended consequence of individual choices of otherwise well-meaning law or regulation but of unhidden public policy that explicitly segregated every metropolitan area in the United States. The policy was so systematic and forceful that its effects endure to the present time.”

Given that the where of housing also affected the who of it, which potential homeowners were likely to be approved for mortgages, there was (and still is) a gap between black and white rates of home ownership in the United States. The appreciation of housing values is one of the main ways that middle-class America has created wealth for itself, wealth that is passed down the generations, thus sustaining those families’ social status. Now rewind: If Black Americans did not have equal access to housing, the knock-on effects meant not having equal access to many of the other opportunities that come with it. You can’t practice your fastball in the backyard if you don’t have a yard to begin with.

Those effects ripple through time, which means that, yes, structural racism is a real thing and that, whether or not one thinks the United States is a racist country, it is still in the throes of past racist policies and that both Blacks and whites of today have either benefitted or been harmed by the way these laws and policies affected those who came before. Whether one then concludes, as the Trump directive had it, that, “the United States is an inherently racist or evil country” is to race ahead to a conclusion not inherent in Critical Race Theory. There has always been a strain of American patriotism that insists on being blind, deaf, and dumb regarding any of the nation’s flaws, particularly when it comes to the subject of race. One argument on the right has been that the best way to move America past racism is to stop talking about race. The prescription assumes an unrealistic amount of color blindness on the part of a nation in which many people who voted for George “Segregation now, segregation forever” Wallace are still alive. It presumes that none of the sickness that tainted their minds and caused them to shout slurs at children just trying to get through the schoolhouse doors was passed on to their children or grandchildren, or that we didn’t recently elect a president whose following is animated by white grievance politics. As Benjamin Wallace-Wells recently wrote in the New Yorker:

It is interesting—and slightly ironic—that critical race theory, with its invocations of structural racism, should be so central to the policy debate right now: part of its teaching is that the patterns of American society can’t be easily dislodged by a change in manners, and that if you are snapping your fingers to make the past disappear you are only doing so in tandem with the rhythms of the past.

To put a finer point on it, you can’t even snap your fingers and dislodge the life of Mudcat Grant, who was born during the Great Depression, a crisis which disproportionately affected African Americans during which Southern politicians prevented them from receiving as much aid as they needed; he was born 12 years before Jackie Robinson was forced past recalcitrant owners into the major leagues; he was born during the lifetime of George Stovey, the last great pitcher who had been allowed to work in white baseball—in the 1880s; he was born in Florida, a Jim Crow state; he was born 30 years before the Voting Rights Act, which was signed into law on August 6, 1965, when Grant was resting between beating the Senators and Red Sox for the 13th and 14th wins (respectively) of his 21-win season. Grant reached the major leagues with Cleveland in 1958 and competed against teams that were still enforcing the color line or had made minimal gestures towards breaking it. When he pitched against the Yankees that season, Elston Howard was the only player of color on the other side (in a moment that hinted at the change then in progress but Grant no doubt didn’t appreciate, Howard homered off of him on June 18 of that year). If he pitched against the Red Sox, it was just him and his teammates, Vic Power, Minnie Minoso, and Larry Doby among them, who represented the true multiracial America.

When Grant signed with Cleveland in 1954, he joined a league in which only four of eight teams had integrated. Those that had limited the number of Black players on their rosters, were hesitant to start a majority of Blacks even if they comprised the team’s best lineup and stepped on any Blacks who wanted to be coaches, managers, or executives. He undertook a profession which required him to travel all over the country despite many sections of the country being inhospitable, being downright dangerous, to people of his complexion.

Even Grant, whose public persona over a long career as a ballplayer, announcer, and musical performer was one of great affability, bumped up against the concept of systemic racism. As the national anthem played on September 16, 1960, Grant, standing in the bullpen, sang not, “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” but, “this land is not free, I can’t even go to Mississippi.” This was in the blackest of humor: Mississippi indiscriminately murdered African Americans. Pitching coach Jim Wilks was offended and the two began to argue, Wilks (a Texan) in racial terms. Rather than throw punches, Grant went to the clubhouse, changed into his street clothes, and left the ballpark. Rather than understand the provocation and commend him for his restraint, manager Jimmy Dykes suspended him for the remainder of the season.

In short, we can’t even talk about James T. Grant, a man who seems to have greatly enjoyed being baseball’s “Mudcat,” without talking about race. If we silence that discussion we silence his story as well. He’s been gone, at this writing, all of five days, and the implication is we should disappear his experiences into the hazy realm of “was” rather than the sharpened land of “still.”

That “still” provokes consternation on the right because from affirmative action to reparations to Black Lives Matter they reject the suggestion that racism didn’t end… when? It doesn’t seem like they’ve given a specific date. Was it 1865? 1965? Baseball-heads will tell you it was somewhere around 1947, but as we’ve seen that’s magical thinking at best, a distortion at worst. Better to give up that cherished illusion and let Mudcat Grant not die but live on as an example, still pitching us forward in time. If you can understand what he lived through you can understand Critical Race Theory. If you can understand Critical Race Theory you can understand what he lived through. Some state legislatures may find ways to tell a different story, but as long as Mudcat is remembered the lie will always show through.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now