Video games, like baseball, have always served as an escape. It’s fitting, then, that the subject of baseball video games, a theme we’ll cover in detail throughout this week, provides an escape from the depressing state of baseball itself. Over the course of the next five days, the authors of Baseball Prospectus will remember, review, and occasionally bemoan a few of the hundreds of games that have been created and played over the past 61 years.

We’ll begin with The Baseball Demonstrator (as titled in IBM’s own product catalog) and continue through, haphazardly and not at all linearly, to the twin titans of the modern age, Out of the Park Baseball and The Show.

The Baseball Demonstrator

Developer: John & Paul Burgeson

Publisher: IBM

Platform(s): IBM 1620

Genre: Simulation

Release Year: 1961

Current Availability: None

Why This Game?: It isn’t the first baseball video game, because there wasn’t any video. And it’s not the first baseball computer game, because it’s not really a game. But it’s the first of something.

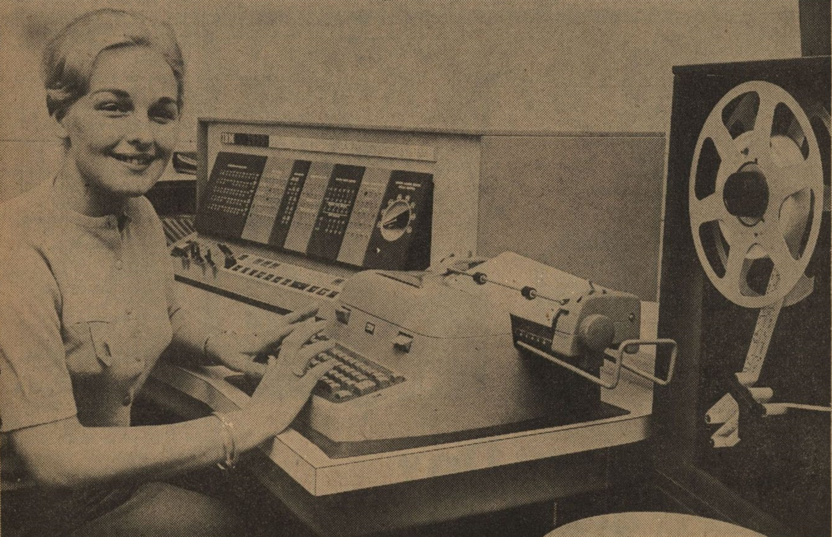

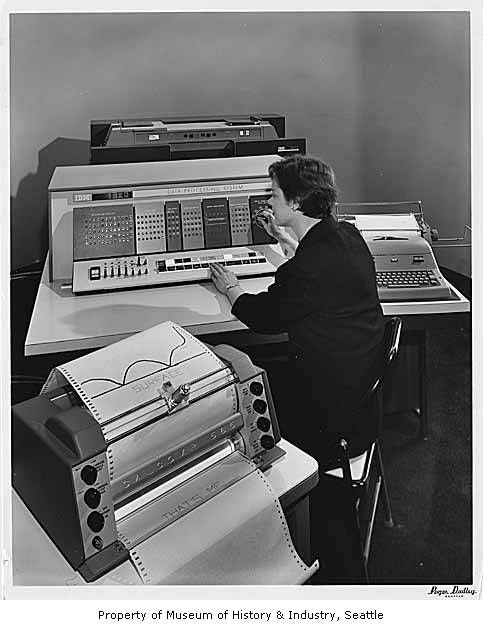

How Does It Play?: The IBM 1620 was marketed as an inexpensive “scientific computer,” one that took up merely a large desk rather than an entire wall. With peripherals, it cost $88,504 ($823,931 in 2022 dollars), which included peripherals like typewriter, printer, and card punch/reader. The machines roared like a vacuum cleaner at full blast.

Burgeson and his brother, both baseball fanatics, enjoyed playing board games with dice and spinners, and the idea of simulating baseball on the tabletop had been around since the late 1800s. An engineer at IBM, John (nicknamed “Burgy,” in appropriate baseball fashion) applied the same concept to the new microcomputer, building a database of 50 historical ballplayers along with their hitting and pitching statistics. (Presaging the great John Dowd, Burgy also threw in a couple of fictional ballplayers for his hometown Clevelanders to give them the advantage.) It was the first time that players of different eras could be pitted against each other, outside of barroom arguments.

Using the typewriter, the player would select a nine-player roster by typing codes into the computer. The IBM would then select its own roster out of a random selection of the remainder. Then, in what must have felt at the time like a telegraph transcription, the computer would begin to print out a description of each play.

(Transcription of a game as relayed in the Virginia Ledger-Star, May 3, 1963.)

Beyond setting the roster, there really is no other input possible for the player, which is why “Demonstrator” is so much more accurate than “Game.” It would be a decade before an English major at Pomona College, Don Daglow, would slip into the labs late at night and devise the first true (though still text-only) simulation game, BASBAL, which would serve as the template for essentially an entire half of the genre, including Out of the Park and Daglow’s own critically-beloved Earl Weaver Baseball.

What This Game Does Better Than the Rest: Today, obviously, absolutely nothing. Firing up an NES cartridge of RBI Baseball and selecting the “watch” mode is more exciting. Or, to create a better parallel, having Out of the Park simulate two random, unchosen teams. And yet, it is a game, in the sense that we make all watching into games: We gamble with ourselves, predict, betting our own mood against the outcome.

The results were compelling enough that in 1961, a Pittsburgh radio DJ called three of Burgeson’s simulated games on the air through play-by-play. It was an event that would be replicated a generation later by Mariners broadcaster Dave Neihaus, who called a fictitious Game 7 of the 1994 World Series. Yet another era after that, the 2020 COVID-delayed season inspired various sources to simulate their own account of the events that should have been. It’s a gene that exists, apparently, in all of us.

Its Industry Impact: Incalculable. Many of the tales of early computer game development and curation, in the era of mainframes, are ones of frustration. Games were seen as frivolous at best and damaging at worst, consuming the attention of students and the processing time and power of million-dollar machines. In 1964, Burgeson wrote a letter to the company politely protesting the deletion of such “novelty” programs:

I am sorry you have felt it necessary to remove novelty type programs from the library. In the economic struggle for survival our company faces, some of these programs have proven exceptionally useful in demonstration of concepts rather than a specific application in a context understandable by a layman. The Baseball Demonstrator program has been used often in this manner to illustrate the concept of computer simulation. As such, I consider it of high significance to the programming community.

The 1960s were replete with stuffed-shirt executives being wrong about things, and this was no exception. Fortunately, IBM relented and restored the program to its library. After all, Burgeson was right: his “Baseball Demonstrator” was a valuable tool for the company, which could use it to demonstrate the machine’s processing power filtered through a complex mathematical language that many people instinctively understood. Metrics like wOBA rely on the implicit understanding of a baseball scale to convey meaning to people; Burgy was, in a very real sense, doing the same.

Fungo: While Daglow went on to become a legend of the video game industry, inventing multiple genres (including the first “god” game, a genre where you look down from the heavens on a world, like Civilization or SimCity) and helping establish a little company called Electronic Arts, Burgeson’s story is a bit more humble. He was an engineer, and after his invention, he went on being an engineer. His program was displayed at The Strong National Museum of Play and documented in the Hall of Fame, and he remained an ardent baseball fan and SABR member until his passing in 2008.

His personal website remains online, acting as a shrine to both the pre-social media era of the internet and to the man himself, a passionate and thoughtful polymath. Among the various and random sections is one devoted to baseball, including links to Diamond Mind Baseball, retrosheet, and various puzzles he wrote for the local paper. (This column, written in 1991, could honestly fit in at BP with a little editing.) Sadly, the materials he includes for his 1961 software are no longer available.

Baseball Demonstrator’s Wins Above Replacement: Undefined, or 10.5. It’s unfortunate that we have to ruin the grading system on day one, but trying to judge this piece of software on the scale of what we think of as a video game isn’t much different than calculating the WAR of a 500-inning-a-year underhand pitcher in the nineteenth century. Burgeson probably did more to progress baseball video games in his life by progressing computers themselves, but I’m glad that in the midst of a lifetime of vital, forgotten work, this one combination of his passion reached the Hall of Fame.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now