And so it happened. Or will happen. That is, if they play again. According to reports, MLB and MLBPA, who spent the winter not agreeing on much of anything, have agreed to some rule changes, starting in 2023. The changes include the introduction of a pitch clock and slightly larger bases. The pitch clock is meant to speed the game along. The larger bases are meant to encourage a bit more base-stealing and to cut down on collisions near the bags.

If they can just work out the pesky issue of money, they can get back to playing.

And oh yeah, they’re going to ban the infield shift. If the 2022 season ever starts, it will be the farewell tour for the most talked about strategic wrinkle of the last decade. This is no small matter either. In 2021, more than half of pitches to left-handed batters took place with three infielders on the right field side of second base.

There’s part of me that ranges from annoyed to angry about this. Some of this being driven by whining from fans who don’t like the idea that the fielders aren’t set up symmetrically. At the same time, there’s reality to deal with. The infield shift really does take some of the action out of the game. Fewer balls go into play and a few balls that would have previously scooted through the infield are picked up and converted into outs by a fielder who isn’t supposed to be there.

The biggest effect of the infield shift, though, is that it increases the number of walks that players take, and for left-handed batters, the number of strikeouts. In fact, (and we’ll see this in a minute) that handedness effect is really important. It turns out that shifting against right-handed batters isn’t a great idea. It does reduce their BABIP a tiny bit, but right-handed batters strikeout far less against the shift than we would otherwise expect of them, walk more, and the overall effect is negative for the defense. In 2021, teams started pulling back from the infield shift against righties. At least half of the shift would have likely extinguished itself.

But according to reports, the shift will be banned no matter your hand. Joey Gallo is out there somewhere celebrating. It doesn’t matter what time you’re reading this. It’s happening. And it’s not a secret who’s going to benefit the most from banning the shift. Left-handed pull hitters (Gallo) will get a few more hits through the right side. Ground ball pitchers will be slightly sadder. And I want to hit those words “a few” and “slightly.” And let’s talk about the math of why.

In 2021, the shift was on in 31 percent of all plate appearances. Using data from 2021, we can see an estimate of the shift’s impact. To get these numbers, I looked at player outcomes when they were not shifted. For example, if Joey Gallo had a .300 OBP when not shifted, and the shift made no difference, then we would expect a .300 OBP when the shift was on. If Gallo had a .290 OBP, it means that the shift was a more effective strategy. For an individual player, the sample sizes will be too small to really conclude much, but if we sum across the league, we can start to get an idea of the shift in general.

Here are the data. A number like +1.4 percent means that hitters did strike out in 1.4 percent more of their plate appearances against the shift than we would have expected based on their non-shift stats.

| Outcome | All batters | RHH | LHH |

| Strikeout | +1.4% | -2.5% | +3.7% |

| Walk | +1.3% | +0.7% | +1.6% |

| HBP | -0.1% | -0.2% | +0.1% |

| Single | -1.5% | +0.3% | -2.6% |

| Double/Triple | -0.1% | -0.1% | -0.1% |

| Homerun | +0.2% | +0.2% | +0.1% |

| Out in Play | -1.1% | +1.6% | -2.8% |

| Ball is “in play” | -2.6% | +2.0% | -3.9% |

| OBP | -.002 | +.009 | -.009 |

| BABIP | -.012 | -.005 | -.017 |

| BABIP on grounders | -.023 | -.003 | -.035 |

| Linear weights per PA | -.002 | +.008 | -.009 |

I promised to show you that righties actually did better than expected hitting into a shift, and there are the numbers. But the shift still worked against lefties. The thing is that because there were still a bunch of shifts against righties, the net effect of the shift on offense overall was actually pretty minimal. Had the shift ban been in place in 2021, those 31 percent of PA with a shift would have been played in front of a more standard 2-2 defense, and among that subset of PA, we would have seen a strikeout in 1.4 percent fewer of them. So the total overall league effect would have been a reduction in the strikeouts per PA rate of 0.4 percent. So banning the shift probably would have reduced strikeouts by one per team per week. Other outcomes will change at roughly the same pace.

That’s it.

It’s not nothing, but as a reference point for scale, from 2016 to 2021, strikeouts jumped two whole percentage points from 21.1 percent to 23.2 percent of all batters. In theory, by banning the shift, we’ll see fewer walks and strikeouts, and more balls in play (and more of them will go for singles), but if you’re looking for the shift to “fix” the game, you’re going to be sorely disappointed. There are other, much more important forces that we need to deal with. Banning the shift isn’t the panacea that people think it is.

And … I’m afraid that we might not even get as much of an effect as the table above suggests.

The numbers in that table above are comparing the shift to a more traditional 2-2 defense where the infielders are roughly equally and symmetrically spaced. In those previous analyses, I’m assuming that teams will revert to standard defense. I’m guessing that they won’t. You’re probably going to see a lot of teams lining up in what Baseball Savant, keepers of the publicly available StatCast data, calls “Strategic” shifts. Sometimes, teams won’t go into a full 3-1 formation, but the shortstop will be just on the left side of second base. It’s the sort of thing that would probably be on the edge of legal under the new rules.

Below, I’m showing the overall numbers for the “traditional” 3-1 shift and these “strategic” shifts. Both of them are being compared to the baseline 2-2 “standard” defense. These numbers are for all hitters, and the traditional column is just copied from above.

| Outcome | Traditional Shift | “Strategic” Shift |

| Strikeout | +1.4% | +1.1% |

| Walk | +1.3% | +0.6% |

| HBP | -0.1% | +0.0% |

| Single | -1.5% | -0.5% |

| Double/Triple | -0.1% | -0.1% |

| Homerun | +0.2% | -0.4% |

| Out in Play | -1.1% | -0.6% |

| Ball is “in play” | -2.6% | -1.7% |

| OBP | -.002 | -.004 |

| BABIP | -.012 | -.012 |

| BABIP on grounders | -.023 | -.004 |

| Linear weights per PA | -.002 | -.009 |

Here’s how to read this table. I estimate that going from a standard 2-2 set to a “traditional” 3-1 shift increases the chances that a batter will strike out by 1.4 percent. If they were to outlaw the shift and mandate a standard formation, then we’d get that 1.4 percent back. But teams aren’t going to go back to a standard formation. They’re going to use the strategic shift, which ends up looking like a junior varsity version of the full shift. Like its big brother, it seems to lead hitters to strike out a little more and walk a little more. Not quite as much, but we were only working with a tiny bit of margin to begin with, and this puts most of that margin back.

Because I try to be a good scientist, I should probably point out that the sample of players who get full shifted are going to be different than the ones who got strategically shifted, and the new rule would force the players in the former category into the latter category and the strategic shift might not work as well for them. But any way you slice it, banning the shift probably doesn’t do a whole lot for the game.

So, what happens next? The shift was always a case where there was never a rule that said that teams must line up 2-2 on the infield, but everyone did it that way until someone did a little creative thinking mixed with math.

Well, if I might indulge in a bit of creative thought, I have a prediction that might surprise a few people.

Warning! Gory Mathematical Details Ahead!

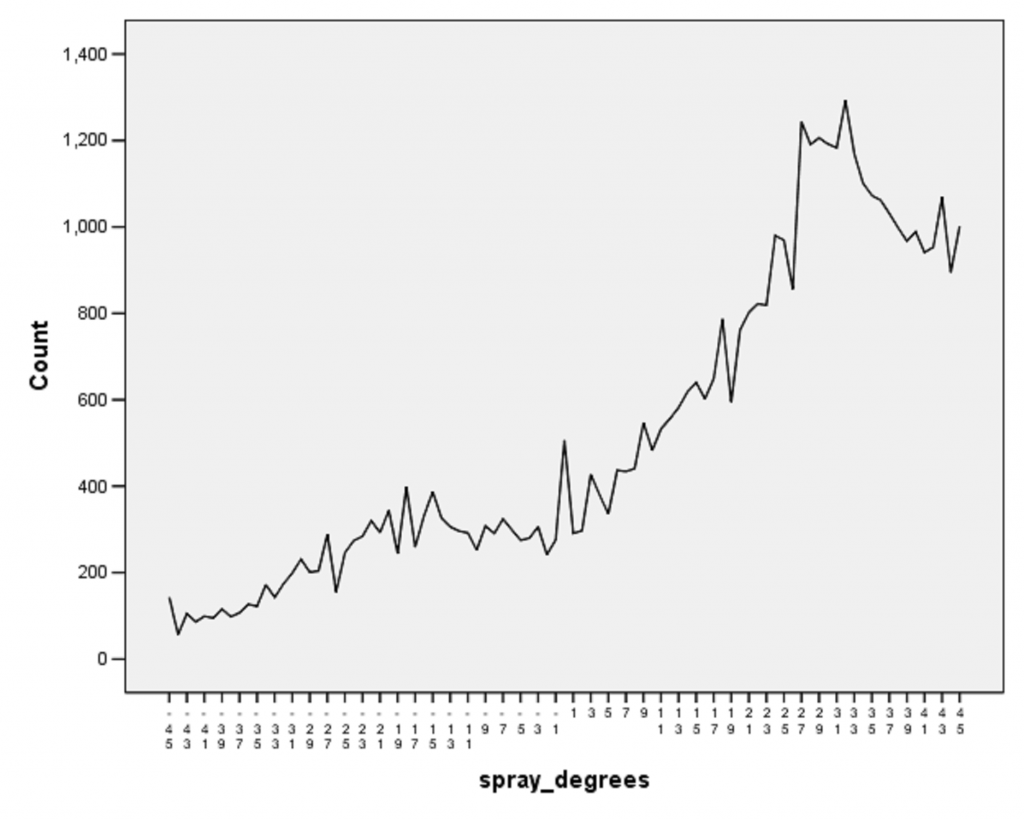

Let me start with this chart. This is for all players, between 2015-2021, who were left-handed and full shifted in more than 25 percent of their plate appearances. It’s a frequency graph of what spray angle they hit their ground balls during that time, with -45 degrees being the third base line, 0 being right back up the middle, and +45 being the first base line.

This shouldn’t be a surprise. Every one expects them to pull. They pull. This is why you have three infielders on the right side to begin with. If teams are banned from doing that, I wouldn’t be surprised to see an infielder playing as close to the second base bag as possible, but where to put that fourth infielder?

The infield shift is as much about what a hitter tends to do often as it is what they do not. Take a look at the left side of that graph (which is the left side of the infield). Yes, the infield shift involves pulling someone into short right field, but it’s equally important that it involves giving up the third base line because the third baseman isn’t actually doing much over there.

Most people would reflexively put the now banished infielder back around the traditional “third base” area, but why? Those left-handed pull hitters are still going to come to bat. They’re still gonna pull (maybe even more now!) Teams might be banned from stacking short right field, but it’s not like those hitters are going to start hitting the ball toward third.

In fact in an infield shift against a left-handed batter, the average third baseman plays at an angle of -12 degrees, and despite being the leftward-most infielder is more or less playing as a shortstop who is very much shaded “up the middle.” Teams clearly aren’t worried about the left side when they see a good shift candidate. Why should they start now?

What if we could find a better use for that fourth infielder? The idea of the infield shift was that by positioning your infielders in an unorthodox manner, it would produce more outs, and… well, that’s the whole point of defense. So where would our fourth infielder possibly convert more balls into outs?

The outfield.

I’ve estimated that an extra outfielder would allow teams to catch more fly balls, to the tune of about 43 points of BABIP on those flies. It makes sense. The more bodies you have out there, the more ground you can cover, and the effect ripples across the whole outfield. It’s not a matter of “multiply by 4/3”, but there is gain to be had. So, which is a left-handed, pull-happy batter more likely to do? Hit a ground ball to the left side or hit a potentially catchable fly ball into the outfield?

I looked it up. For that group of heavily shifted (more than 25 percent of PA) hitters, they hit fly balls and line drives to the outfield that did not go over the fence about five times more often than they hit ground balls that went anywhere to the left side of second base. You have to do a little bit more math to “get there”, but I’ll just point people here if you want to know all the gory details, and for the rest of you, just know that I checked. It works.

They couldn’t run a four-member outfield every single time, because when you start playing with three infielders, you can run into coverage problems if there are runners on base, but there is going to be a significant chunk of plate appearances in which – in the absence of allowing a third infielder on one side of the diamond – a fourth outfielder is the next best option.

MLB can nip that one in the bud. They probably will. The rule could be written to declare that in addition to not allowing more than two infielders on either side of second base, you need to have four fielders on either the infield dirt or infield grass. They actually did this in the minors in 2021 and could easily do so now.

The purported reason for banning the shift is that players see it and say “I don’t want to hit the ball on the ground, because it’s going to get gobbled up. Instead, I will hit the ball over the shift.” And if you’re going to hit the ball in the air, you want to hit it over the outfielders too. This produces a style of play that is more reliant on power (and strikeouts), and less on singles and other balls “in play” that the fans allegedly want to see. If that’s the case, then MLB should probably welcome teams using a fourth outfielder. Now, hitters need to think a little more carefully about hitting the ball in the air. There are more people out there to catch the ball that you just got a little too far under. Instead, they’d be better off pulling the ball along the ground, which is apparently what MLB wants more of.

If MLB is going to say “no fourth outfielder,” then they need to explain why. One answer might be that that they don’t actually care about the style of play it promotes. “People have come to expect that the fielders will be set up in a certain symmetrical pattern and we’re going to give them that. A fourth outfielder or a 3-1 infield looks weird.” Now we’re in a battle for the soul of the game. I can perhaps begrudgingly understand where MLB is coming from on wanting to ban the shift to put a little more action into the game. It wouldn’t be much, but every little bit helps. But if we’re going to ban stuff that would likely further that same goal, just because it looks weird, now MLB is taking aim at creative thinking.

But maybe there is a good reason for banning the fourth outfielder after all. Systems were made to be gamed. It’s not like the creative thinking will ever stop. If MLB bans “three infielders on one side” but allows fourth outfielders, well, when a left-handed pull hitter comes up, I simply declare that my team is now in a four-outfielder formation and Smith over there… well, Smith is on the outfield grass (see, not an infielder!) playing “short right field.” Then they’ll have to legislate how deep the outfielders need to be playing, and that’s a losing game.

But the end result is mandating a third baseman, whom we know doesn’t have much to do and whom we know could be in a better place, to stand there. And it won’t matter much, but it will look better on TV.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

All that to say, thank you for this interesting and thoughtful comment!

Defensive positioning isn't a problem. Deep pitch counts (per at bat) and the difficulty to hit modern pitching is a true problem in today's MLB. Implementing 3 things will greatly help the game:

1) Move the mound back. Nothing is sacred about 60'-6". Move it back 2 feet and balls hit into play will increase.

2) Raise the bottom of the strike zone (pre-1995 rules defined the top of the knee cap as the bottom of the strike zone, the rule implemented in 1995 changed it to the bottom of the kneecap).

3) (a) Implement Robo umpires to call taken balls and strikes. This may require redefining the vertical dimension of the strike zone to a set size.

3) (b) Modify the definition of a called strike depending on the count. With a 0-strike count, a called strike must have the entire ball pass through the strike zone. With a 1-strike count, a called strike must have the center of the ball pass through the strike zone. With a 2-strike count, a called strike must partially pass through the strike zone (this last one is how the current strike is defined). With a smaller volume to work in early in the count, pitchers will not be able to nibble around the plate early in an at-bat, which will cause more balls to be pitched over the plate early in the count which will encourage batters to swing at pitches early in the count knowing there is a smaller volume to work in. The result is more balls hit into play, fewer long at-bats, shorter games, etc.

There is also some data on the prevalence of out-of-play foul balls as contributing heavily to more pitches per PA, but I don't know how that gets addressed.

I agree that multiple foul balls with 2 strikes make the game longer, but I don't think its a large contributor. I'm open to some rule change here (3rd foul balls with 2 strikes will result in strikeout), but currently any rule that increases strikeouts is the wrong move to make (maybe when MLB strike out rates lower to 15% it would be OK).

I know there have been pitch clocks in the minors and I'm curious if there is data to see what affect there might be on pitch speed. We might not know for sure the full effects because of all the ball changes, but there might be some trend lines to dig out.

Side note, they removed the fake the 3rd-throw to 1st pickoff play...can they just change the rule so pitchers have to step off the rubber? It never made sense that southpaws could do that ol' step to 1st move as long as their leg didn't cross an imaginary plane. We don't have many SB these days anyway, just simplify the rule and have more SB attempts.