If you were to ask anybody what the biggest surprise of the 2021 season was, the answer you would most often hear would be a simple “the Giants.” Projected to be a mediocre team by most prognosticators, they laid waste to the National League en route to a league-leading 107 wins, relegating the Dodgers to the unfamiliar turf of a single-elimination wild card game, then taking them the distance in a classic five-game set in the division series. Gabe Kapler ran away with Manager of the Year, the pitching staff churned out breakout arms like a production line, and the offense scored over 800 runs for the first time since Barry Bonds was rewriting record books.

If “surprising” was the thematic descriptor of the 2021 Giants, then mark it down that “regression” seems to be the presumptive word of choice for the team entering 2022—according to the projection systems, at least. PECOTA once again thinks their roster is lacking in top-end quality and has them pegged for around 77 wins. Notably, the system believes the bats will crater back to earth, expecting them to score only 679 runs after lighting up scoreboards to the tune of 804 last year. One year after finishing second in the NL in scoring, PECOTA thinks they will score fewer runs than the Pirates. Clearly something in the projection is hesitant to buy into the sudden gains the team made in 2021.

This isn’t going to be me telling you to not buy into the Giants this upcoming season or that PECOTA has a vendetta against them. Instead, I want to get to the root changes that sparked the offensive revival at Oracle and hopefully understand whether the results were coincidental or if something is happening that fundamentally changes the players on this roster. When a team exceeds expectations by this much, it’s always worth examining what they’re doing to set themselves apart.

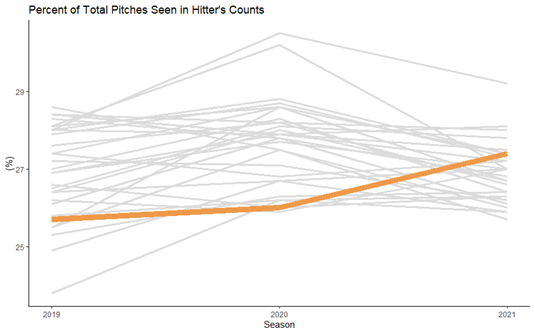

Organizationally, San Francisco has steadily ingrained teamwide philosophies offensively since Farhan Zaidi was hired in November 2018. Chief among these tenets has been a better approach while at the plate—the Giants have seen a higher share of pitches in hitter-friendly counts each successive season since 2019, finishing seventh in the league by that measure last year:

With those favorable counts come favorable pitches to hit, and indeed the Giants led baseball in slugging percentage while ahead in the count, with a robust .592 mark. Much of this was driven by success against fastballs, which have been another point of emphasis for the organization under Zaidi and co. Just look at how they’ve fared in slugging on contact over the last four years against fastballs:, four-seamers, sinkers, and cutters:

| Team | Season | SLGCON vs Fastballs |

| SFG | 2018 | .516 |

| SFG | 2019 | .542 |

| SFG | 2020 | .600 |

| SFG | 2021 | .637 |

They’ve improved on the preceding season each of the last three years, culminating in them finishing second (and just barely: .63671 to .63666) only to a star-studded Dodgers lineup in SLGCON against fastballs in 2021. (An aside: Oracle Park did make some hitter-friendly renovations prior to the 2020 season that aided the slugging improvement to some extent.)

Part of the reason they have been able to punish velocity so effectively is how they deploy their players. Perhaps no organization has a better grasp on the strength of their individual players than San Francisco does now. Gabe Kapler and his coaches were able to mold this group of past-their-peak veterans and unheralded castoffs from other organizations into a 107-win juggernaut by constantly placing their hitters in situations tailored to their skillsets. They ranked sixth in baseball in percentage of plate appearances while enjoying a platoon advantage—to be expected of a team that features noted platoon specialists like Wilmer Flores—but that was just the surface of it.

Beyond simply matching up against pitcher handedness, the Giants created advantageous situations based on the paths of their players’ swings and opposing pitchers’ pitch shapes. Against pitchers who leaned on high four-seam fastballs, they would rotate in a player who has a more level swing. Against a sinkerballer they would start a player with more of an uppercut “launch” swing geared towards hitting pitches at the knees.

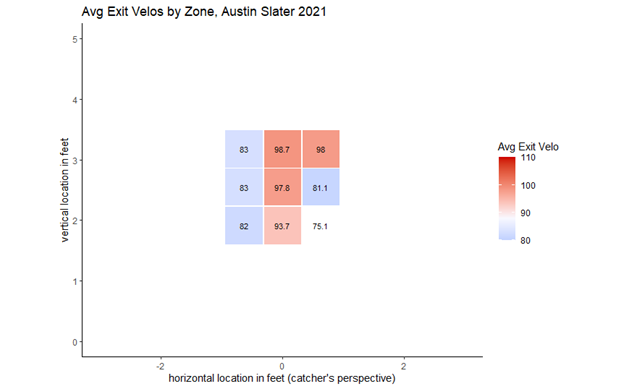

As an example of the former, take Austin Slater; he is a great high-ball hitter who struggles against breaking stuff below his knees. For his career before 2021, he had slugged .524 with an average exit velo of 90.2 mph on pitches in the top half of the zone. In the bottom half those numbers fell to .323 and 88.2 mph; the book was written on him before he ever touched a bat last season. And yet he still supplied a 101 DRC+ in 306 PA as a valuable backup at all three outfield spots, ensuring the Giants were getting league-average or above production even while rotating their regulars. He was even their second-most frequently used leadoff hitter.

Slater was able to do this because of the way the Giants utilized him: he faced pitchers who leaned on shoulder-high fastballs as the cornerstone of their arsenal and mostly saw fewer opportunities against sinkerballers. His exit velos by location explain why:

We can see that he has a level swing, which produces his loudest contact high in the zone; the pitch most often thrown there is a fastball with 10-plus inches of “rise” or induced vertical break (IVB for short). In 2021, 14.1% of all pitches in the league had 10-plus inches of IVB; for Slater, that number was 17.5%. The Giants put him in situations that catered to his strengths, presenting opponents with an uncomfortable choice: pitch to his weakness and away from the pitcher’s strength, or go with their best stuff and put pitches right where Slater wanted them. Most chose the latter, and judging by his .632 SLG on high fastballs, that may not have been the best decision.

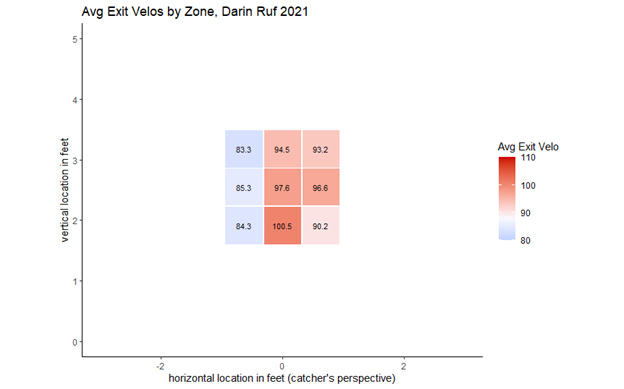

Darin Ruf represents the other side of the same coin: his flaw has been high and hard four-seam fastballs for his entire career—entering 2021 he had a .397 career SLG on high four-seamers—but he crushes nearly everything else. He fares particularly well on pitches with moderate drop, in this case those with only 0-10 inches of IVB, and these happen to be pitches commonly thrown lower in the zone: sinkers, cutters, and less spin efficient four-seamers. Looking at where he hits the ball the hardest, it’s clear his swing is geared to punish those areas:

22.9% of pitches last year were sinkers or four-seamers in the lower half of the zone; thanks to the way the Giants deployed him, those pitches represented nearly a quarter of the pitches (24.6%) Darin Ruf saw in 2021. The result? A positively Bondsian .730 SLG on fastballs in the lower half.

Ruf and Slater are just a pair of examples from a dozen instances like this—these tactics are the reason why a team perceived to be lacking in top-end talent was able to accrue 13 regulars with a 100 or better DRC+, with a 14th coming just short (Alex Dickerson, 98). The next-closest team, the White Sox, only had 10.

In many ways this is the Rise n’ Grind method of roster construction: what the Giants lack in raw talent they make up for by exhausting every possible in-game advantage. It is a distinctly Rays-y brand of baseball but supported by a larger payroll, although Zaidi has not yet shown a willingness to flex that financial muscle with a superstar addition. Will it prove a successful strategy again in 2022? The league is sure to be wiser this time around, but we can be equally sure the Giants will be unearthing new ways to gain that extra tenth of a percent.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now