At some point, people will stop being surprised. Last week, Clayton Kershaw faced 21 batters and retired all 21, but Dave Roberts sent a reliever out for the eighth. And of course, the sky was falling. Just like it was after Game Three of the 2021 World Series in which Ian Anderson had a no-hit bid going through five innings, but was replaced in the sixth. And just like it was when Blake Snell was pulled from Game 6 of the 2020 World Series. And Wade Miley was pulled in the 2018 playoffs while cruising.

I can’t say I blame anyone on either side of the Kershaw argument. I fully understand the logic behind taking Kershaw out there. I also understand the frustration that something so perfect was so close, and yet didn’t happen.

It’s not like it’s new. In 2004, Cleveland was hosting Detroit in an April game when Cleveland starter Jeff D’Amico couldn’t get any of the first six Tiger hitters out, gave up four runs, and then it rained. And hailed. An hour later, when the tarp came off the field, on came Jake Westbrook in relief. Westbrook quietly dispatched the next three Tiger hitters to get out of the first inning. And then eighteen more. After seven perfect innings, Cleveland manager Eric Wedge took Westbrook out of the game, which by that point was tied at 4. Cleveland lost 10-4 as Rafael Betancourt and Scott Stewart imploded in the eighth.

Wait, 2004?

Thus spoke then-manager Eric Wedge after the game.

“He did more than his job tonight and I thought I left him in a little longer than I should have,” Wedge said. “I can’t keep him out there and put him in harm’s way. We tied the score and put our setup guy in, but it just didn’t work out.”

Westbrook was disappointed, but said he understood the decision.

“I felt like I could go another inning, but he was just looking out for me,” he said. “It’s probably the best stuff I’ve had in a big league game. I had a good sinker and changeup.”

It’s almost like protecting the arms of pitchers is something that managers have been thinking about for a while, particularly early in the season. And while the Kershaw decision predictably launched a thousand tweets about the game being “dead to me,” sources tell me that it continued the next night.

***

There’s been for a while an unspoken shift in pitching usage that we need to talk about. Everyone knows that the average start now lasts just a bit more than five innings, and even if you control for the “opener effect” and look for the pitcher who recorded the most number of outs for each team, that doesn’t move the needle much either. It’s a relievers’ league.

But I don’t think that fully captures what’s going on here. I think that this normally gets labeled as “Pitchers aren’t as able to sustain as they used to be” when that’s not the case. If you want to understand modern pitching usage, you need to remember seven words.

Everyone is a reliever. Even the starters.

Fifty years ago, pitching revolved around a model that a pitcher was out there until either the game ended or the pitcher clearly didn’t have it anymore. And then a reliever came in to do the same thing. There was effectively one style of pitching. Some were better at it than others, and teams naturally put their four or five best pitchers into the rotation, with the rest either picking up spot starts or sitting in the bullpen. If a manager went to the bullpen, sort of by definition, the pitchers out there were there because they weren’t as good as the starters.

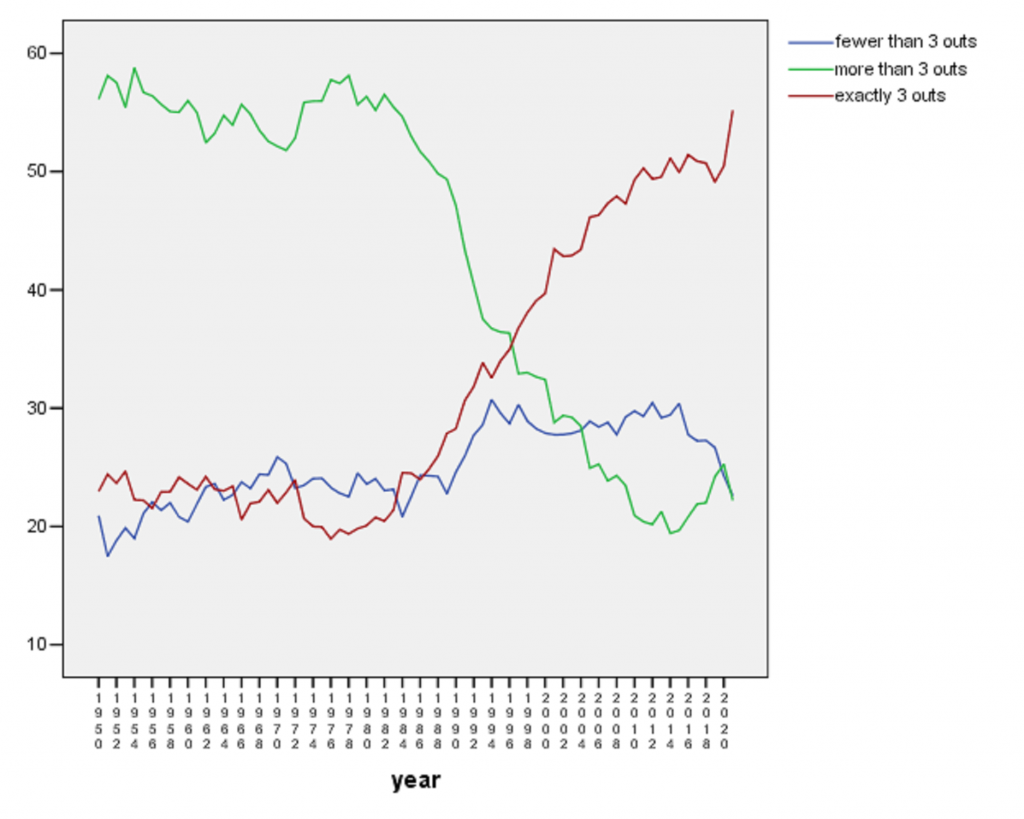

This is one of my favorite graphs. It shows how in the 1980s, there began a change in how relievers were used. It used to be that relief appearances were multi-inning affairs. Now, the majority of them last exactly three outs. Most people focus on the short-burst nature of that sort of outing. That’s part of it. The evolution of the micro-relief appearance has enabled a new type of pitcher, one who doesn’t have the stuff to turn over a lineup, but has enough to face off against a couple of hitters. It was a new way to be a pitcher.

And it worked. Teams realized that these short-burst relievers could be better on a per-batter basis than the long-form relievers, and there came a point in the game where a few of them could tag-team and be better than letting the starter go forward. As more of these relievers emerged, that tipping point moved further and further back into the game.

In 2021, the average starter, going through the order for the third time, had a slash line allowed of .262/.327/.453. The average reliever had a slash line allowed of .238/.321/.395. Those are averages, but by the end of the sixth inning, when the starter is guaranteed to be going through the opposing lineup for the third time, you can imagine that in an eight-member bullpen, there are likely to be three pitchers out there who are above league-average for even relievers, which is in turn, better than a third-time starter. If a manager is thinking about winning today’s game, then it’s pretty obvious which route makes the most sense. And as teams are able to identify and develop more relievers, that tipping point pushes further and further back into the game.

As a point of reference, if we go back 50 years to 1972, relievers had an triple slash line allowed of .244/.325/.347, compared to starters on their third time through with .250/.310/.374. It wasn’t always clear that a reliever was actually a better option.

If you’ve been watching baseball since the mid-1990s, this probably feels familiar. Teams began to have closers, and “set-up” relievers and “seventh-inning” relievers. And the terminology highlights an important piece of that development. Those three outs are confined to one inning. But there’s a hidden piece in there: the built-in endpoint. All of those pitchers went out there knowing that there was an endpoint to their outings, even if they had a 1-2-3 inning and were in fine form that night.

With pitchers being judged not by how long they could last, but by how well they could complete a specific mission, they didn’t have to worry about “saving a little bit.” This is the “max-effort” pitcher that we’ve come to know and love. The reason the pitcher can do that is that you can let the tank run empty when you know there’s an endpoint.

As the short-burst model developed, a few things happened. One is that it turned out that there were a lot of pitchers who did pretty well with that way of pitching, many of whom would have never been given a chance in the old model. And at first, there seemed to still be a cultural expectation that the starters’ job was still to go as deep into the game as possible, even if everyone understood that complete games were fading away. As knowledge progressed and we learned about the injury risk inherent in long individual outings, we started to see pitchers on 100ish-pitch limits. While that was technically an end-point, it was also the sort of end-point that was more about the physical maximum that a pitcher could tolerate. Still, teams learned that there were a lot of relievers around who could handle things, even if the pitcher was out after the sixth inning.

As that balance shifted further back, teams began realizing that for some pitchers, it made sense to pull them before they even got near 100 pitches. They… generally were the ones who weren’t that good. Teams began learning about the third time through the order penalty. But even then, rosters had expanded to include so many relievers and they were of a sufficient quality, that teams could do that.

Pitchers started entering games with pre-determined end-points that were strategic. Teams were taking a pitcher who was perfectly capable of throwing 100 pitches and leaving some of those pitches “unused” in service of a better outcome. Why push a pitcher to complete a game or even go deeper into a game if someone else has a better chance to get those outs? Complete games are neat, but they aren’t often the best way to win a game, much less to preserve a pitcher’s health.

I’d argue that the idea of a pre-determined end-point to an outing is what really launched the reliever evolution. There were pitchers who didn’t start, but they were failed starters and they pitched like starters. The modern reliever is a new species of baseball player.

We’re now seeing those pre-determined end-points moving into the starting rotation. It might be six innings or 18 batters or 100 pitches, but the effects are going to be similar. With an end in sight, a starter can ration the energy meter to fit the job. It’s a much larger job in terms of innings covered, but there’s an end-point. If end-points were what made pitchers into relievers, then (just about) everyone is a reliever now.

If you want to understand modern pitching usage, you have to understand how those end-points have re-shaped pitching strategy.

***

So let’s come back to Kershaw. It was a special case, because while Kershaw was “only” at 80 pitches, Kershaw has battled injuries and experienced a shortened spring training. It was a defensible decision, something that Kershaw specifically pointed out after the game. The reality though is that we’re going to have another one of these at some point, a pitcher being pulled after five or six no-hit or perhaps even perfect innings. And while that will be a rarity, there will be the more common days when a starter is shown to the shower after five or six innings of one-run ball. The fans will wonder why.

The answer is that if you have an end-point, you have to stick to it. And what they’ll probably miss is that the end-point might just have been the reason for the good outing. In the third inning, maybe the pitcher reached back for a little extra to get that key strikeout in a situation that might have spiraled into a three-run inning. But knowing that it was going to be a five-and-dive anyway, the pitcher might have said “Well, why not here?”

If you’re one of those people who saw the Kershaw decision and thought that the end was near, you were probably more right than you thought. Everyone is a reliever now. And it’s the end-points that have changed everything. The fault isn’t in our starters. The game is just played differently now.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

I do not understand why what is true of a large enough randomly chosen subset of the appearances of the group "all pitchers" is therefore true of Blake Snell on a good day.