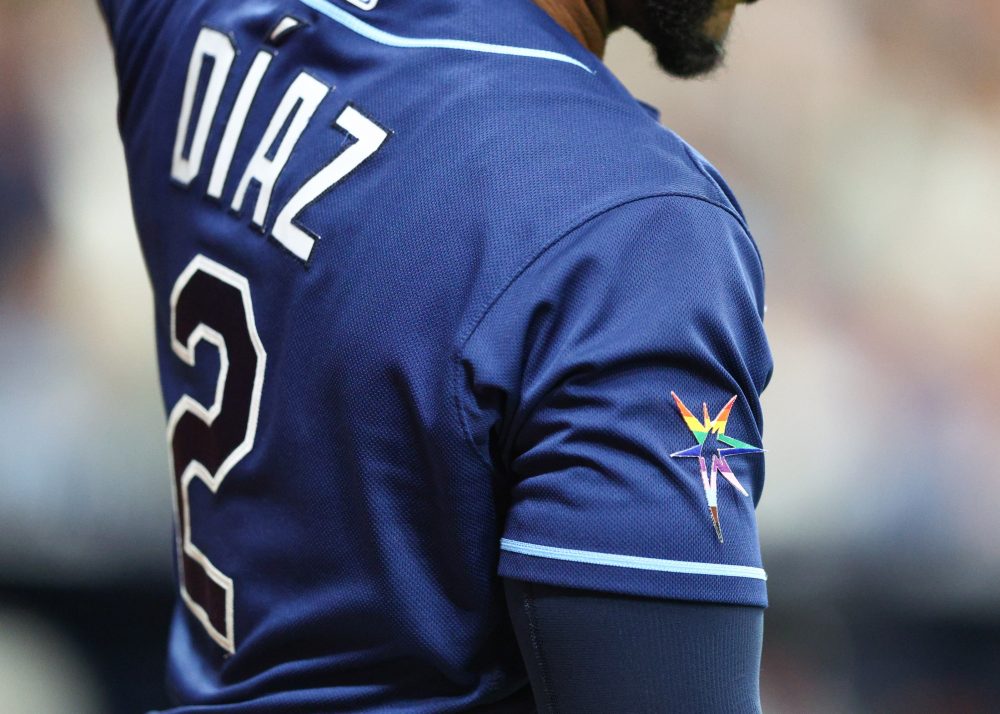

Last Sunday the Tampa Bay Rays had a promotional event, Pride Night, in support of the LGBTQ+ community. They botched it. Several pitchers refused to take the minimal step of wearing some rainbow icons. Asked why, reliever Jason Adam said, “We believe in Jesus.” A few days later, our writer/editor Ginny Searle noted in these pages the incongruity of the Rays celebrating inclusiveness on a corporate level while denying it individually, with the result that a prejudiced player like Adam ended up with a platform he wouldn’t otherwise have had.

Ms. Searle also noted that whether or not one cites religion in support of hateful views those views are still hateful. This is, unfortunately, one of the contradictions inherent in most religions, and a major use to which they have been put over time such as when, before the Civil War, the Bible was used to rationalize slavery. It’s nothing new, and nor is observing the contradictions inherent in religious traditions that on one hand promote humanist ideals like, “THOU SHALT NOT KILL” but also contain celebrated tales of slaughtering the Other. Those who interrogate religion in a serious way—both faithful and not—have grappled with those mixed messages for literally thousands of years in an effort not to impugn spirituality but to clarify it. The only thing that is novel about the present iteration of this very old conflict is that it was provoked by a major league baseball team and concerned major league players and thus became something that was not only fitting for us to discuss but something we were required to cover.

Baseball has always been greater than bats, balls, gloves, and thoracic outlet surgery. It’s been Fleet Walker and Jackie Robinson; Lizzie Arlington and Dottie Kamenshek; Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson; Honus Wagner and Mickey Mantle; Jim Devlin and Shoeless Joe; Steve Howe and Alan Wiggins; King Kelly and Billy Sunday; Hank Aaron and Alex Rodriguez. We’ve had the sacred and the profane, the sober and the debauched; the pure and the corrupt, and, perhaps most of all, those who aspire and those who have been thwarted. Among the latter you might find a Joe Hauser, who on the brink of a great career had one of his kneecaps spontaneously break in half and thereby render him a minor-league journeyman rather than a major-league star, and you also might find dozens of players akin to Cool Papa Bell, who had the gifts to be the first coming of Tim Raines or Rickey Henderson but instead was restricted to the Negro Leagues and, eventually, custodial work simply because arbitrary, unfeeling authorities said “No.” Baseball is a story of thousands of forgotten games played in the furtherance of becoming—or failing to become.

America is the story of thousands of forgotten lives spent in the furtherance of becoming—or failing to become. Thus baseball contains everything Americans are and are not and reflects those images back at us so that we might see ourselves. Sometimes we see that reflection, are dismayed by it, and make changes in turn, as in the game’s grudging termination of the color line. Other times, we don’t see ourselves at all and things go on as they have. “Lord, baseball is a worrying thing,” the Hall of Fame pitcher Stan Coveleski said in The Glory of Their Times. “There’s always someone sitting on the bench just itching to get in there in your place. Thinks he can do better… Back to the coal mines for you, pal!” We’ve yet to address the compulsion implicit in Coveleski’s lament, which is to say that in a just society no one who preferred an alternative to the coal mines would be forced to go. It’s one of so many questions, waiting for us to find them, haunting baseball.

The rest of the game is fun but transient. Championship teams come and go with a dizzying speed that impugns their uniqueness—we haven’t had a repeat World Series-winner since the 1998-2000 Yankees, and it’s natural to wonder if anything so ephemeral can be worthy of remembrance. A home run or a great play sparks a momentary cascade of dopamine and then it’s gone. One can observe that Ty Cobb made 4,189 hits but they cannot be experienced by any of the five senses; we may as well say he ate 4,189 chocolate pies and try to taste them. Perhaps the thought of Babe Ruth’s 714 home runs provides more of a visceral tang when conjured by the imagination, but surely that is because of who Babe Ruth was rather than the home runs themselves. Babe Ruth as a person rather than as an accumulation of numbers brings us full circle. The valuable part of baseball, the part that lasts, is who we are, who we were, who we might be. We were the people who rejected Cristobal Torriente but accepted Ichiro Suzuki and one day might also accept… who? Someone considered in the Rays’ Pride Night, perhaps.

Ms. Searle’s piece provoked a large number of comments by our standards, many of them supportive. We also had a few readers cancel or threaten to cancel their subscriptions. It’s hard to tell from their remarks whether they did so because they objected to the not-particularly controversial points she made or because we addressed Rays Pride Night at all (“I hear Baseball HQ actually focuses on real baseball articles and analysis” [emphasis added]). Risking reader backlash is a feature and not a bug of this publication as well as any other that purports to supply its audience with incisive commentary and analysis rather than pandering to them. The latter results only in a stale, trite, cowed site that would have very limited value in an age of information commodification. So much of today’s news comes predigested via social media. We exist, as we have existed, not because you need a rote rundown of who-hit-what or who-pulled-which-groin—those things existed before BP—but because we try to get it what the news really means. That encompasses wondering who will catch for the Reds now that (alas) Tyler Stephenson will miss most of two months and what it says about a supposedly rebuilding team that it has but one good young position player (two if you count Jonathan India, lost on the Hamstring Sea since April), but it also includes asking if Rays Pride Night was transformed into the opposite of what was intended.

In all cases you’re free to disagree with the conclusions we reach. We love that because it means you’re engaged, and that in turn means we did our jobs. It is also our great privilege to learn from you when you engage us in reasoned debate. That said, we reserve the right to defend the values of this publication, among them that baseball is everything that it touches and, as it touches everything, we have a broad mandate. Every day we publish pieces that color within the lines of straight baseball news and fantasy analysis, but we do other things as well. (Our daily menu is never a zero-sum game; no topic pushes out any other.) This publication has never restricted itself merely to the game between the foul lines. It has never treated baseball as pure escapism. It was founded to challenge the complacency of thought that had had a stranglehold on the game going back to the 1800s. The nature of what we question has necessarily evolved over time, but that is keeping with being a living publication and not Godey’s Lady’s Book. That expansive mission can be a challenge to us and sometimes a challenge to you, and we recognize that. What we hope is that we’re all on this journey to greater understanding together.

These days, “together” is a very big ask. We are living through a time of division and conflicting values. One suspects that Ms. Searle’s piece garnered some of the reaction it did because one of the major fault-lines of our time is inclusivity, with a faction in our country demonizing (among others) LGBTQ+ Americans generally and a vulnerable minority in trans people specifically. Gender and sexuality, difficult, highly personal matters, have been hauled into the public square and represented as a threat. Through this form of demagoguery is tribalism perpetuated—you name a group, identify a threat to that group—real or imagined—and circle the wagons. That group coheres, donates together, votes together, and, in select places, murders together. (That is not to say that all political thought leads to violence, but that violence is the logical extreme of existential us-versus-them, “save the children/we will not be replaced” forms of panic/identity politics.) It makes finding even a starting point for discussion difficult. “It’s amazing.” Said one of our dissenting commenters, “to watch the people who speak about diversity nonstop call diversity of opinion bigotry or any other slur intended to destroy the people with a different opinion on an issue.” That is, by pointing out bigotry one is discriminating against the bigot. If we can’t get past, “I’m not prejudiced, you’re prejudiced,” it’s hard to believe we can ever come together on anything.

And yet we have to try. It is our great fortune that baseball gives us a window into all of these things, a general way we can discuss all the issues that vex and animate us, while retreating, as needed, to the safe ground of what’s-wrong-with-the-Phillies and what-isn’t-wrong-with-the-A’s and whether we might see another Yankees-Mets World Series this year. But even then something odd will happen. Jackie Robinson Day will come around again, or someone will recall what Hank Aaron went through as he climbed towards the home-run record, or a comparison will be made between the ethics of Mark McGwire and those of various Houston Astros, or Curt Schilling will be back on a Hall of Fame ballot or Josh Donaldson will say something stupid to Tim Anderson or some right fielder will say that getting vaccinated caused insect wings to grow out of his shoulder blades. Once again we’ll be talking baseball, but also talking about so much more.

See, baseball is there for beer and peanuts and crackerjack, for root-root-root for the home team, but it’s for all of that other stuff too—and so are we.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now