This article was originally published in January 2023 as part of the Baseball Prospectus 2023 Annual.

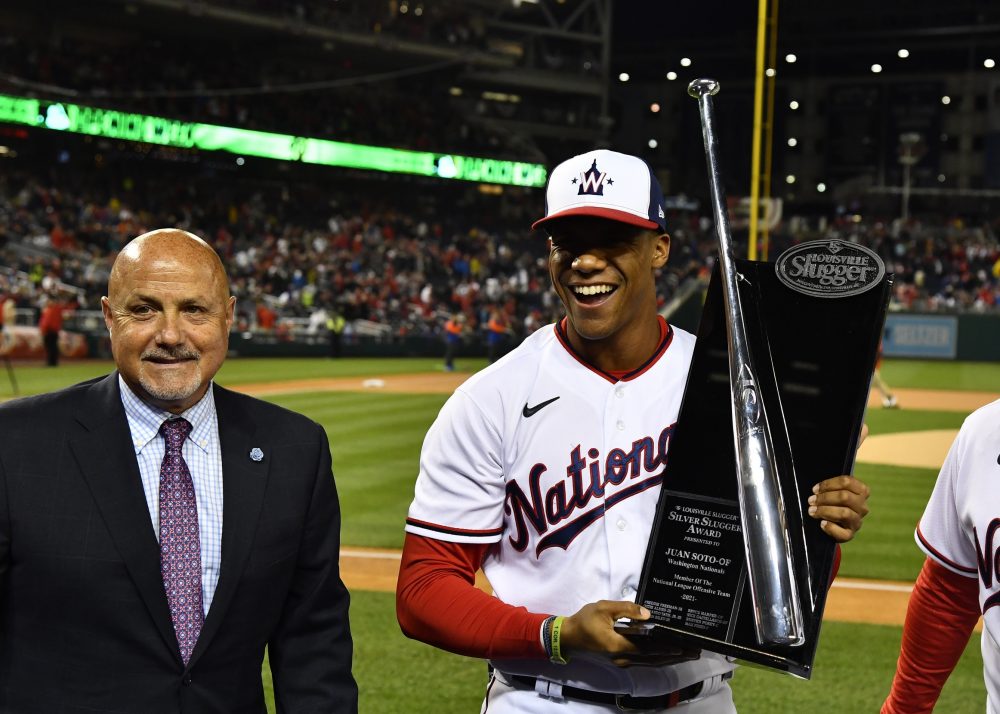

When Juan Soto took the field for the 2022 Home Run Derby, he knew it was likely the last time he’d don a Nationals jersey on the national stage. Two days earlier, Ken Rosenthal reported Washington’s extension negotiations with Soto had broken down. The team’s final offer—15 years, $440 million—would have been the largest contract in MLB history by total guarantee, but only the 20th-highest in average annual value, a pittance for the entire prime of one of the game’s best hitters. Despite longtime Nationals general manager Mike Rizzo‘s repeated vows earlier in the spring and summer that he would not trade Soto, the 23-year-old superstar was now very, very publicly on the trade block over two years before his free agency.

Soto told the media that afternoon that he was “really uncomfortable” with the series of events. Then he went out and hit 53 homers in a wildly entertaining Derby, ousting retiring legend Albert Pujols in the semifinals and besting rookie sensation Julio Rodríguez in the finals. A jubilant Soto dropped to one knee upon his victory and launched his bat as high in the air as he could, then held a dance party on the field. It was without a doubt the best moment for the Nationals since their 2019 World Series win, the face of the franchise winning a marquee showcase in great style. How could you not want more of that? How could you decide your team is better off without Soto than with him?

Fifteen days later, Juan Soto was traded to the San Diego Padres.

The Soto trade was the end of a long collapse of process for the Nationals, not the beginning. For years, they’ve just been picking the wrong players.

Rizzo is a scout’s scout. It’s literally in his blood; his late father Phil was an inaugural member of the Professional Baseball Scouts Hall of Fame. And when the younger Rizzo took over control of the Nationals’ baseball operations before the 2009 season, his scouting-above-all mindset was squarely in line with player acquisition orthodoxy, perhaps even a little ahead of the curve. Early on in his tenure, it seemed like they couldn’t miss on high draft picks, with a particular knack for getting top talent with signability concerns like Anthony Rendon and Lucas Giolito to fall to them on the board.

But over the last 14 years, the times have changed, while Rizzo has largely stayed the same. Analytics are now embedded in every facet of player acquisition and development across the industry. Washington does use them to a degree, but over time, the Nats have leaned on traditional eyeball scouting more than most—if not all—other organizations. They have very good eyeball scouts, to be sure, but that just is not enough to keep up with the Joneses anymore.

In recent times, the Nationals have systematically overvalued hitters who look good by traditional scouting methods—sweet-looking swings, nice shows of power in batting practice, old-school notions of physical projectability—while ignoring glaring flaws exposed by analytics—poor in-zone contact rates, low exit velocities, high chase rates. Last year, they drafted Elijah Green with the fifth overall pick despite near-historic swing-and-miss concerns; in 2021, they popped Brady House, who struck out almost five times as much as he walked at Low-A. They’ve been similarly myopic on the pitching side, consistently acquiring pitchers who throw hard but don’t get whiffs on their fastballs and have major durability question marks. Before House, they selected four straight pitchers in the first round—Cade Cavalli, Jackson Rutledge, Mason Denaburg and Seth Romero—who threw hard, couldn’t get whiffs and got hurt.

As their drafts got worse and worse over the last decade, the Nationals’ farm system quickly degraded. They have paired poor drafting with poor player development; there just haven’t been success stories of hitters unlocking power from a new swing path or pitchers learning great sweepers to pile up more whiffs. They ranked as a bottom-seven farm system in every season from 2019-22, and that overstates what they’ve gotten out of the minors since Soto graduated. Other than Soto, the last Nationals draft pick or international signee who was a solid regular for the team was Rendon—drafted in 2011.

Nevertheless, Rizzo’s keen eye for veteran talent in trades and free agency kept a contending ship afloat for years, and Soto’s ascension as a teenage superstar in 2018 looked to extend things indefinitely. Entering 2020, the defending champions were not only looking like one of the best teams in the National League but seemed reasonably well positioned for long-term contention. PECOTA projected Washington as the favorites to win the NL East behind a core of Soto (under team control through 2024), budding superstar shortstop Trea Turner (under team control through 2022) and longtime veteran ace Max Scherzer (signed through 2021). Rendon left as a free agent that offseason, but top prospect Carter Kieboom stood waiting in the wings to seize the third base job. It looked like good times were here to stay in the Navy Yard.

Few things went right in the pandemic-shortened 60-game schedule. Sure, Soto led the league in batting average, OBP and slugging percentage as a 21-year-old, and Turner hit .335; they finished fifth and seventh in MVP voting, respectively. But Scherzer had a down year amidst a host of other injuries and underperformances. They missed a 16-team playoff format by three games.

Rizzo ran it back again in 2021, adding sluggers Kyle Schwarber and Josh Bell to the mix. Entering July, they were right in the middle of the pennant chase, only 2.5 games out of the division lead, and 2020 looked like it might be a blip. Then they skidded out of contention with a pair of five-game losing streaks, and moved to a seller’s posture at the deadline.

Trading Scherzer as a rental to bolster a weak farm was a logical move. In a far less logical move, Rizzo sweetened his Scherzer trade with the Dodgers by adding Turner, netting top prospects Keibert Ruiz and Josiah Gray. Combined with a weak farm, moving on from Turner made a Soto trade a virtual inevitability. Without Turner or significant outside spending, Washington simply didn’t have enough good players or prospects to compete by 2024—and the Lerner family no longer showed interest in huge free agent deals.

Were the prospects coming back from the Dodgers worth all this trouble? It’s early, but signs are pointing toward no. Ruiz is settling in as a decent starting catcher, albeit one who chases outside the zone a ton and doesn’t hit the ball very hard yet. Despite plus velocity, Gray’s fastball was one of the single worst pitches in the majors last year, and he’s going to need improvements in pitch design and usage—things that the Nationals have heretofore proven unable to teach. They’re useful players, but neither looks like a future star worth giving up on a contention cycle for.

Four years before moving on from Soto, the Nationals were faced with another monumental decision on a face-of-the-franchise outfielder, Bryce Harper. Rizzo almost traded him to the Astros at the 2018 trade deadline for a package of prospects who ultimately didn’t amount to much, but ownership stepped in and blocked the trade.

How can you trade Bryce Harper? He presented the same problem, or the same opportunity perceived as a problem, as Soto. Washington tried to extend him instead, ultimately offering a 10-year, $300 million contract that September, but Harper rejected the deal because it had too much deferred money. So the Nationals moved on, choosing to spend much of their Harper budget on Patrick Corbin instead. Flags do fly forever, and one must consider that Corbin was a down-ballot Cy Young candidate and World Series hero in 2019. But he’s been one of the worst pitchers in the majors since, while Harper continued to be one of the best hitters in baseball in Philadelphia. It’s conceivable that Harper alone would’ve extended Washington’s contention cycle through Soto’s prime.

Meanwhile, the Nationals had one of the top prospects in baseball to replace Harper in the outfield. Not Soto, who was already established by then, but Victor Robles, who had recently been the second-best prospect in the entire minors.

The late-2010s were a time of great change in the valuation and development of hitting prospects. Exit velocities and zone-contact percentages have since become a standard part of public player evaluation, but MLB didn’t even collect this sort of data in the majors in an organized, encompassing fashion until 2015. It would be a couple more years before Trackman units were fully adopted in the minors and data was freely shared around the industry, and a couple more years after that before public side analysis truly reflected what teams had learned: that it’s pretty important to hit the ball hard and make a lot of contact swinging at hittable strikes.

Robles’ power was consistently scouted as the weakest of his five tools, with fringe-average to average potential. He was a top prospect regardless because scouts graded him with a plus or plus-plus hit tool and Gold Glove-caliber defense in center field. He came up for good in September 2018, and from then until the end of the 2019 season he slugged .430 with 20 home runs in 683 plate appearances.

Underlying the adequate topline production was an implosion in Robles’ hard-hit data. His average exit velocity dropped from 87.7 mph in 2017 to 83.3 mph in 2019, edging out only the historically punchless Billy Hamilton. Robles tried to bulk up before the 2020 season to hit the ball harder, and his batted ball metrics went further in the opposite direction. Entering 2023, Robles has now put up four consecutive seasons of bottom-five average exit velocities and three consecutive seasons of pitiful offensive performance. His vaunted plus-plus hit tool as a prospect has produced a .233 career average.

Replacing Rendon with Kieboom has gone even worse; at least Robles plays a great center. Kieboom has battled a bunch of injuries—he missed all of 2022 after undergoing Tommy John surgery—but when he’s been on the field he’s been absolutely terrible both at the plate and with the glove. He can’t hit a major-league breaking ball to save his life, and his exit velocities have been nearly as poor as Robles’. His hit tool was supposed to carry his offensive game, and instead he’s been under the Mendoza Line so far.

So you might think that when choosing the prospects for the Soto trade—a trade in which Rizzo could’ve selected the best prospects from half the teams in baseball even before throwing in Bell, one of the top rental bats on the market—the Nationals would’ve learned some lessons about swing decisions, in-zone contact and batted ball data, right?

Well, they really didn’t.

The Nats did grab one prospect with unquestionably huge hitting potential in James Wood, San Diego’s 2021 second-rounder. The long levers on his 6-foot-7 frame belie above-average contact skills. He blends that contact ability with good swing decisions, and his batted ball data is stellar. That’s the basic framework for a top global hitting prospect—unlike any Washington has developed since Soto—and, indeed, Wood is already the no. 3 prospect in the game. So at least at the top, the Nationals actually did get the right guy back.

The rest of the return…well, it has a lot of familiar-sounding beats that don’t bode well for the future. Let’s start out with CJ Abrams, a former top-10 global prospect. Like Robles and Kieboom, he projected for a plus-or-better hit tool from a traditional scouting perspective. His exit velocities have been a concern dating back to high school—if you ever see a phrase like “projects for gap power” in a scouting report, that’s not a positive—and, sure enough, his hit tool collapsed in the majors as a rookie last year. His already-suspect swing decisions completely fell to pieces too, leading to a chase rate north of 40%, and other than speed and old scouting reports it’s hard to find much to like in his offensive profile.

They also got Robert Hassell III, the eighth pick in the 2020 Draft and the no. 26 prospect entering 2022. Hassell has one of those sweet, smooth lefty swings that is guaranteed to make every scout in attendance swoon and project a plus-plus hit tool. But similar to Abrams, he doesn’t do anything tangible to actually produce a plus-plus hit tool. He doesn’t hit the ball hard, and he makes only an average amount of contact with average swing decisions for his age. His slugging percentage in both High-A and Double-A after the trade started with a two, and his prospect stock is already tanking.

The pitching side of the deal also played to recent form. MacKenzie Gore was the best pitching prospect in the game three years ago before he stopped throwing strikes. He found the plate enough in 2022 to be minimally effective in the majors—although his mid-90s fastball no longer fools anyone—and got included in this trade, right after he bled velocity and ended up on the IL for elbow inflammation. Jarlin Susana is probably the hardest-throwing teenager on the planet, which sounds great except that almost all of the previous hardest-throwing teenagers on the planet didn’t turn into productive major leaguers. Will he be the exception? We’ll find out some time in the mid-to-late 2020s.

Somehow, Washington made the Soto deal without getting Maryland native Jackson Merrill, San Diego’s 2021 first-rounder. Merrill popped up very late in the 2021 draft cycle, going from off the board to the 27th-overall pick in just a couple months, and he’s continued on a meteoric rise since then. His swing is not as aesthetically pleasing as Hassell, but he combines great feel for contact with great exit velocities and above-average swing decisions. Basically, he does all of the things Hassell and Abrams don’t do. He’s a top-15 prospect in the game, and would’ve been within a stone’s throw of Wood to be the top piece in the deal—except he wasn’t in it.

So how do the Nationals fix their broken development wheel?

The Lerners announced last year that they’re exploring selling the team. The easy path is finding some decabillionaire who wants to run a $300 million payroll to turn things around quickly while simultaneously dumping many millions more into developing the superstars of the 2030s. But Jeff Bezos seems more interested in the NFL at the moment.

A more plausible positive trajectory sits an hour-and-a-half north on the Acela train. It wasn’t so long ago that the Philadelphia Phillies were right about where Washington is right now. Their major-league club bottomed out pretty hard in the mid-2010s, with a five-year run of 63- to 73-win teams. Worse, they clearly had no idea how to evaluate or develop batters, blowing three consecutive top-10 picks on hitters who couldn’t hit, including 2016’s first-overall pick, Mickey Moniak. As late as the 2013-14 offseason, their entire analytics department consisted of a part-time extern on loan from the league office.

Eventually, the Phillies realized they had a major problem and made extensive personnel and philosophy changes from top to bottom, culminating with hiring Dave Dombrowski to head their baseball operations two years ago. Dombrowski is just as rooted in old-school team-building as Rizzo, with almost 35 years of experience leading franchises and a longstanding reputation for contention at all costs. But in recent years he’s blended his priors with more modern stances, including elevating Sam Fuld, whose expertise lies in analytics and sports science, as his general manager. Their investments in analytics, scouting and player development have led to modest improvements in hitting development outcomes—no superstars yet, though Alec Bohm and Bryson Stott are useful regulars—and they’ve gotten quite good at unearthing and nurturing young pitchers. To cover that they’re still not that great at developing bats, they’ve aggressively acquired star position players on the open market, including Washington’s own departed cornerstones Bryce Harper and Trea Turner.

The Nats can get on that track, if they want to. They’ve finally started staffing up in analytics, player development and sports science—18 new positions for 2023, per Jesse Dougherty of The Washington Post. As in Philadelphia, admitting you’re deficient and hiring new faces is the first sign of progress. They landed the second pick in a loaded 2023 Draft, which should provide another near-term boon to the farm. Unlike their last rebuild, they won’t get to take slam dunk prospects like Stephen Strasburg and Harper in consecutive years—the new draft lottery and other anti-tanking provisions in the CBA loom large—but they should be able to nab someone to pair with Wood at the top of the farm system.

Having better analytics and smarter people in the lower ranks of the organization is a low bar to clear, which augurs well for the potential quickness of the fix. But those changes won’t be enough on their own. The Nationals need more than adjustments at the periphery, an addition to the roster of folks making suggestions. They need a leader who will listen to what they say and, crucially, let it overrule what he and his scouts see. Rizzo must start melding his traditionalist’s mindset with today’s evaluation and development methods—or whoever ends up owning the team has to replace him with someone who will.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now