It seems as though I’ll never be free of Jacob Stallings. In December of 2021, with the Annual in its stretch run and a dozen essays in second drafts, the league saw a flurry of transaction activity, much of which I was obligated to analyze. Among them was a head-scratcher of a trade: the Pirates were sending their starting catcher, Stallings, to Miami for a minimal return and signing a more expensive Roberto Pérez to take his place. Sleep-deprived and irritable, I laid into the Pittsburgh brass for the move. Eight months later, I wrote a Transaction Analysis Analysis about the move, in light of the fact that Stallings was wretched in his first three months in the Sunshine State. He pulled out of his tailspin by the end of the year, but in two years in Miami, he established himself not as a cheap quality starter, but a run-of-the-mill 200 PA backup.

That he went to Colorado to fill a similar role is no surprise; guys like Stallings are what the Rockies specialize in, especially if they have sad eyes. What is a surprise is that at the age of 34, the catcher has had what can’t be described as a revival, because he’s never hit like this before. Through Wednesday his OPS+ stood at 126, more than double his Marlins output. Regression will come, rest assured, but the idea of Stallings even being capable of a dozen weeks of this kind of offense is bizarre. Even more so: he’s completely flipped the script on his former reputation. While scorching the ball, he’s also one of the 10 worst catchers in baseball defensively, by CDA.

Catching isn’t a young man’s game—Stallings earned 72 plate appearances before his age-29 season—but it isn’t really an old man’s game either. It’s the hardest position to play, murder on the knees, and requires the most responsibility and savvy of any defensive occupation. To forgive the cross-sport comparison, catchers have the shelf life of running backs, combined with an importance far closer to quarterbacks.

One thing I noticed when looking through PECOTA’s preseason projections this year was how kind it was being to these masked graybeards. Projection systems make their metaphorical money by prediction regression in the face of narrative and being right 55% of the time, so this shouldn’t have been a shock, even if these guys were trying to bounce back from both being old and being catchers. (For this section we’re using the all-encompassing DRP rather than framing runs, but; because framing dwarfs all other aspects of quantifiable catcher defense, the effect is negligible.) Here’s the list of regulars who were projected to see significant time in 2024, from age 33 up:

| Catcher | 2024 Age | 2023 DRP/80 G | 2024 Proj DRP/80 G |

| Martín Maldonado | 37 | -12.4 | -8.3 |

| Yan Gomes | 36 | -5.7 | -3.9 |

| Travis d’Arnaud | 35 | 3.7 | 2.0 |

| Yasmani Grandal | 35 | 6.3 | 4.4 |

| Salvador Perez | 34 | -7.5 | -8.4 |

| Kyle Higashioka | 34 | 10.7 | 8.8 |

| Austin Barnes | 34 | 0.0 | 5.2 |

| Jacob Stallings | 34 | 3.0 | 1.7 |

| James McCann | 34 | -0.4 | -0.8 |

| J.T. Realmuto | 33 | -4.3 | 4.4 |

| Christian Vázquez | 33 | 5.1 | 2.7 |

| Luke Maile | 33 | -4.2 | 0.5 |

| Elias Díaz | 33 | -9.0 | -5.8 |

Nearly without fail, PECOTA drew a line between last performance and zero, and picked a spot in the middle. Outliers like Realmuto and Maile had built up such a catalogue of good defense that the system was willing to overlook a single bad year. The question is: Is this how catcher defense works? Can an old dog learn new tricks, and compared to the mysterious arts of hitting and pitching, are there even new tricks to learn at this point, given that at this point even the most wizened of catchers developed in an era of pitch framing? And given the number of pitches a catcher sees, compared a hitter’s plate appearances, do catchers just catch too much for natural variations to appear in a year’s work?

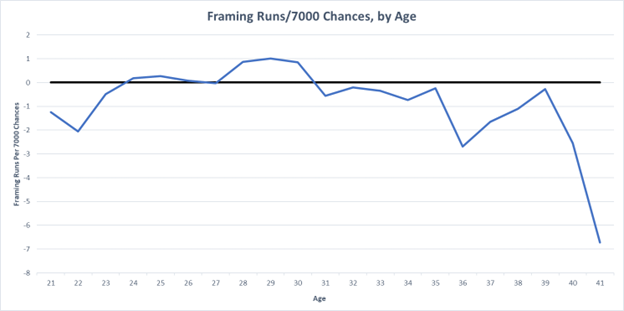

To study this I took the year-over-year framing-run values of every catcher season with at least 500 pitches received, from 2011 to 2024. If a player missed a year but returned a year later, either from injury or the minors, I used the next major-league result instead. The result was 1,103 pairs of seasons.

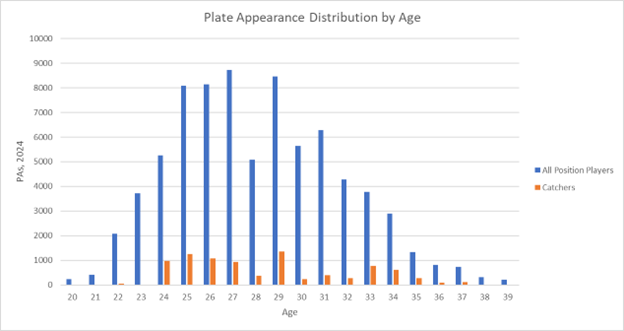

Framing by age, as a total, still looks like this:

The left edge is mostly major prospects whose bats demanded playing time before the nuances of defense had time to be instilled, including names like Kyle Schwarber, William Contreras, Salvador Pérez, and Jesus Montero. Age 39, frustratingly, remains the Mathis Zone: His ageless brilliance that season, and the lack of catchers who even make it that long, ruins the curve. Otherwise, the general rule: a catcher’s peak value comes in his late twenties, falls off a little in his early thirties, and falls off a cliff after 35. But these are averages: how much noise do we see within them?

First, we’ll look at catchers up to the age of 30, using a range of 0-5 framing runs as a slight change and anything more (or less) as a major change:

| Catchers, Ages 22-30 | ||||

| YTY Seasons | Major Decline | Slight Decline | Slight Improvement | Major Improvement |

| 652 | 34.8% | 17.2% | 16.3% | 31.8% |

Pretty even across the board, though the distribution is a little surprising, with two-thirds of seasons marking a volatile change. The decline isn’t perhaps totally shocking, given that many of these younger catchers were in the process of washing out of the job, while the others were establishing themselves as regulars. Let’s move on to a more established group of veterans.

| Catchers, Ages 31-35 | ||||

| YTY Seasons | Major Decline | Slight Decline | Slight Improvement | Major Improvement |

| 307 | 40.1% | 19.9% | 13.7% | 26.4% |

It’s interesting that the proportion between major and minor on both sides of the scale remain at 2:1, but now rather than being even with each other, a catcher has a 60/40 chance of declining in a given year. Now let’s move on to our endangered senior citizens:

| Catchers, Ages 36+ | ||||

| YTY Seasons | Major Decline | Slight Decline | Slight Improvement | Major Improvement |

| 55 | 53% | 18% | 18% | 11% |

Now rather than 60/40, we’re looking at 70/30. Which is still surprisingly high, and probably fairly reflective of how hitters perform year over year. It turns out that framing does bounce back, even when the flesh becomes weak. There are probably a couple of factors here: Though we’re using 7,000 chances as a way to simulate a full workload, for the sake of creating a large enough sample of year-over-year results, we’re admitting a fair number of 1,000-2,000 pitch seasons, which are more susceptible to variation than a full workload. And also, injuries still exist, and can heal.

So with that, let’s take a look at how PECOTA has done so far with its indefatigable conservatism.

| Catcher | 2024 Age | 2023 DRP/80 G | 2024 Proj DRP/80 G | 2024 DRP/80 G | 2023-24 Delta |

| Martín Maldonado | 37 | -12.4 | -8.3 | -6.6 | +1.7 |

| Yan Gomes | 36 | -5.7 | -3.9 | -20.8 | -15.1 |

| Travis d’Arnaud | 35 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 0.3 | -3.4 |

| Yasmani Grandal | 35 | 6.3 | 4.4 | 12.0 | +5.7 |

| Salvador Perez | 34 | -7.5 | -8.4 | 0.5 | +8.9 |

| Kyle Higashioka | 34 | 10.7 | 8.8 | -0.5 | -9.3 |

| Austin Barnes | 34 | 0.0 | 5.2 | 0.6 | +0.6 |

| Jacob Stallings | 34 | 3.0 | 1.7 | -8.4 | -11.4 |

| James McCann | 34 | -0.4 | -0.8 | -5.5 | -5.1 |

| J.T. Realmuto | 33 | -4.3 | 4.4 | -9.1 | -4.8 |

| Christian Vázquez | 33 | 5.1 | 2.7 | 8.2 | +2.7 |

| Luke Maile | 33 | -4.2 | 0.5 | -15.8 | -11.6 |

| Elias Díaz | 33 | -9.0 | -5.8 | 2.6 | +11.6 |

Three of our 12 catchers have seen major improvements on a rate basis so far this young season, including two catchers in Perez and Díaz who are making a push to post career seasons both at the plate and behind it. Stallings and the small-sample Maile are on the other side of the spectrum, but both pale before the utter collapse that is Yan Gomes, whose attic portrait got destroyed in the exact moment he drank from the wrong grail. These numbers will almost all even out more as the season’s shadow grows, but by the end, several of these guys will have rebranded themselves, for good or for ill.

***

A confession: I try to write pieces like this in real-time, doing the math as I go, partially because I like to carry that exploratory tone in my writing, but mostly because I want to minimize the time I’m bummed because I’ve run into yet another null hypothesis. I tend to think of articles like this as writing broccoli, the sort of thing that’s not bad for you but not really exciting to eat or fulfilling to cook. That’s how it goes, though, sometimes; we can’t always bake cakes. (The cakes are GIFs in this metaphor.)

Besides, as much fun as it would be to be right about something and look clever in the process, it’s honestly better for the game that there is this much variation in catcher defense. It helps keep familiar faces employed for longer, which is pleasant in itself, but it also keeps another piece of the game shrouded in mist, and therefore safe from analysts like myself. And it keeps Jacob Stallings safe, comfortable knowing there’s a chance, if not quite an even one, that his glove recovers to compensate for when his bat inevitably cools. At least, until he goes and has an Elias Díaz season next year, and I have to write a Transaction Analysis Analysis Analysis.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now