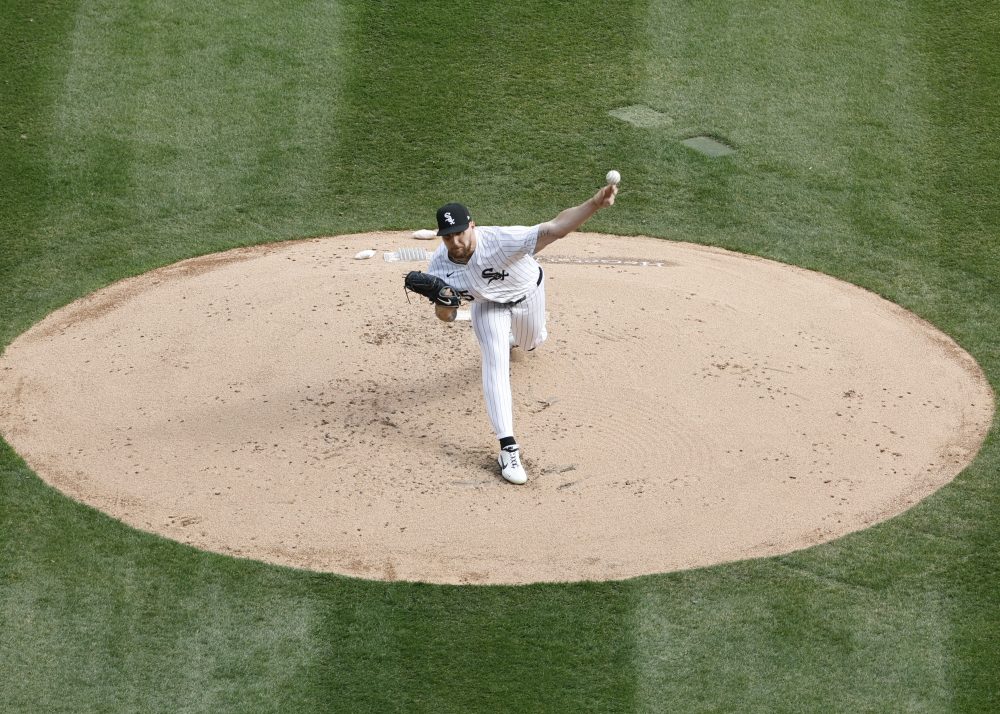

Just last week, Ginny Searle detailed the trade candidacy of Garrett Crochet. Yesterday, it was reported that he has “no interest” in moving to the bullpen, and will only pitch in the postseason if he signs a contract extension with the team that acquires him. What could happen was already messy, clouded by Crochet’s current team being the league’s current leader in bungling talent. Now, it’s even more complicated.

While Crochet’s input on the situation might draw diverse and colorful opinions, it’s reasonable to ask how much more he can throw this year. If you’re inclined to think anecdotally, Matt Harvey’s 2015 season still ripples out for how dangerous it can be to throw away an innings limit. His 219 frames that year appeared to be the first triumph in a hero’s journey but ended up as the harbinger of a Greek tragedy, with natives gathering at the steps of the palace only to realize it’s for mourning rather than celebrating. The righty never sniffed an innings total that high for the rest of his career. Like quarterbacks in the NFL, frontline pitchers are coveted and treated like a protected class.

Crochet has thrown 89 ⅓ innings more this year than he did last year. That’s a jump 10 innings higher than the next closest guy, Trevor Rogers, and nearly 30% more than the increase that Ryan Feltner has seen in his workload. Going back to 2018 (and [shakes fist] excluding 2020-21 because of the pandemic), it’s the 14th-biggest year-over-year increase for any pitcher. And that’s just so far. As noted last week, he’ll still start another 8-10 games. He’s averaged 65 pitches over his last four appearances, and though he’s gotten there with a wide range of pitches per outing it might just be where the White Sox want him the rest of the way. He’ll climb the ranks even if they or a new employer limits his workload.

The 14 names ahead of him can be broken into a couple of different groups. Here’s the first one:

| Player | Season | Year-over-year Innings Increase |

| Yu Darvish | 2019 | 132 ⅔ |

| Noah Syndergaard | 2018 | 126 |

| Miles Mikolas | 2022 | 121 |

| Jeff Samardzija | 2019 | 113 |

| Adam Wainwright | 2019 | 109 ⅓ |

| Wei-Yin Chen | 2018 | 103 ⅓ |

| Zach Eflin | 2023 | 100 |

| Shane Bieber | 2022 | 97 ⅓ |

| Carlos Carrasco | 2022 | 91 ⅔ |

| Jeffrey Springs | 2022 | 90 ⅔ |

This data includes any pitcher who threw at least 10 innings in a given season. It also includes minor-league innings to avoid the inclusion of someone like Hunter Brown, who threw a bunch of frames as a starter in Triple-A before being called up. In any particular full season, there were between 619 and 674 qualifiers. So far in 2024, there have been 552. The goal was to cast a wide net to capture as many big jumps as possible.

Of these 10 pitchers, five had hit or eclipsed 200 innings in a season as a major leaguer, and eight had registered at least 191. Combined, they spent at least part of 72 seasons on a major-league roster before their big jump in innings from one year to the next, which was almost exclusively driven by injury. The only exception is Springs, who hasn’t been able to stay healthy since his lone full year in the rotation. By and large, this is a group of experienced players who knew—had been able to learn—the limits of their bodies and how to maneuver through long, arduous seasons.

Here’s the other group of players who have had bigger year-over-year jumps than Crochet has to this point of the season:

| Player | Season | Year-over-year Innings Increase |

| Andrew Heaney | 2018 | 137 |

| Michael Soroka | 2019 | 118 ⅓ |

| Bailey Ober | 2023 | 94 ⅓ |

After injury issues early in his career, Heaney reached a career high in innings as a 27-year-old in 2018 (186 ⅓). By WARP, he was two-and-a-half times more valuable that year than he has been in any other season in the big leagues. A large part of that has to do with stints on the IL and transitioning to being more of a swingman as he’s gotten older, but that’s never anyone’s first choice. It’s even more extreme with Soroka, whose 3.1 WARP in 2019 on the back of 174 ⅔ innings accounts for 75% of his career value. He, too, has been ravaged by injuries and hasn’t crossed even 90 innings in a single season since then. He’s finally settling into a relief role with the same White Sox team that is trying to determine how to handle Crochet, and might be determining the rest of his career.

Though Ober has been a relative success by following up on last year’s strong campaign with another one this year, it’s hard to say if he truly offers a different possibility for Crochet or any pitcher suddenly stacking innings. Like Heaney, his big jump came when he was already in his age-27 season, and he’s on pace to push his career high in innings. With a fastball that comes in a hair under 92 mph, he also throws softer than Heaney did relative to the league. He does it with an outlier frame that is the biggest frame of anyone discussed here, being listed at 6-foot-9 and 260 pounds. He’s been a starter for the duration of his professional career.

Something else to consider: Among all of these names, Crochet’s average fastball (97.1 mph) is harder than everyone’s in the year of their innings jump except Syndergaard’s (97.7). His efficiency can’t be questioned—he’s thrown more than 90 pitches in just nine of his 22 starts—and it might be hard to call any game a high-stress situation for Chicago. Still, with higher velocity being attached to the likelihood of injury, and injury driving much of the despair on these lists, the best way to handle Crochet is unclear. The sample pool is small and its examples are hardly encouraging. His exceptional skills and lack of track record mean he doesn’t have a comparable, which makes him an unknown in a game that seeks to define everything. Facing that uncertainty, it’s understandable why the young man is seeking stability on the business side.

Maybe it would be easiest to reference Crochet’s name to thread the needle. The difference between crocheting and knitting is subtle. The stitches in crocheting are knotty, meaning the fabric yields less. In knitting, the stitches stretch. If you call a person who crochets a knitter, or vice versa, they might give you dagger eyes. You want to get it right, but like most things in life, allowing for give can keep you from an outright collapse.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now