Most references to chaos theory center on the seeming fragility of order in complex systems—the butterfly effect. As popularized by storytellers, rather than scientists, the big takeaway from chaos theory is: There’s chaos coming, and you can’t stop it. You can’t predict what will lead to a cataclysm. When in the presence of chaos, beware hubris, and oh, by the way, you’re always in the presence of chaos.

The real thrust of the theory, though—the more remarkable finding, when first scientists and mathematicians pieced it all together—is that underlying order exists at all. The close study of these seemingly random systems revealed patterns, feedback loops, and organization, which wasn’t really the expectation. Like the old joke about laws passed by Congress, chaos theory is named for the very thing it seemingly undermines. Yes, chaos is very real, and it’s always knocking at the door, but there are more lattices of order beneath what we see as chaos than we often notice, even in nature.

So, maybe when A.J. Hinch made his wisecrack last week about turning to “pitching chaos” whenever it wasn’t Tarik Skubal’s turn in the Detroit rotation, he was winking at us all a little bit. Unlike any especially open-minded geniuses who set themselves to the task of examining abstract chaotic systems as a concept, none of us ever expected real chaos under the hood. We knew the Tigers, like every other team, would do their best to put together rosters and plans that would maximize their odds of winning, and we assumed there to be some rational underpinnings to those choices. Then again, the temptation to dismiss Detroit as a team that benefited hugely from sagging would-be contenders and a bloated playoff field was strong, and who among us had heard of Brant Hurter, Keider Montero, or even Jason Foley when this season began? It did feel like true chaos, to some extent, facilitated by a system that regrettably rewards moderate competence and then magnifies randomness by compressing the game of the long season into a bunch of short, confused clashes.

It’s time to give the Tigers more credit than that, though, and not just because they’re on the verge of advancing to the ALCS. There are concrete clues that this team is doing smart things behind the scenes, and that the pitchers no one had heard of even the last time Cleveland and Detroit played each other are legitimate assets to a playoff-caliber team. Let’s climb inside the mind of Hinch and his staff.

The Guardians should have smelled trouble as soon as Hinch said this to reporters, as reported by the Detroit Free Press late Tuesday afternoon:

“We’re going to talk about it today,” Hinch said. “I’ll talk to (pitching coach Chris Fetter) today and the rest of our group, and we’ll devise the plan on how we’re going to lay out the beginning of our pitching.”

Hinch said he would inform Cleveland on Tuesday night.

“So that they can build their lineup and build their strategy as well,” Hinch said. “We just haven’t come to that determination yet. We’ve got a lot of options.”

Everybody but Tarik Skubal and Reese Olson will be available.

He made it sound so sporting, so simple and human. He wouldn’t want to go into a game unprepared, so of course, he wouldn’t want Stephen Vogt to have to do so, either. It was, of course, a trap.

Hinch was as good as his word, as far as it went. He told the Guardians Tuesday night that Keider Montero would start, and Keider Montero started. That, in itself, is shocking, and should remind us we’re dealing with much more than rolls of the dice or shrugs of the shoulders. Montero signed out of Venezuela for $40,000 a little over eight years ago, and the Tigers (magnanimous, again, in their honesty) let it leak when he made this roster that it was at the expense of former first-overall pick Casey Mize, specifically because they liked Montero’s pitch mix better against the Guardians than Mize’s.

Teams say that kind of thing all the time. Occasionally, it’s just a smokescreen. They know more than you or I do about these players, and they know we all know that, and they use the vague idea of superior information to disguise decisions made for logistical or personal or political reasons as ones made out of secret baseball wisdom from the fourth dimension. Most of the time, though, there’s actually something to it, and if you wanted to see what there was to this one, you didn’t need to look any further than the first inning of Wednesday’s game.

When a team picks one fringe pitcher over another for a playoff series, they’re not really picking them because of how they like their mix against the entire roster of the other team. The cases in which that kind of systematic advantage for one pitcher over another exists aren’t really about matchups; they’re about one pitcher being clearly better than the other. No, picking guys for surgical strikes in short playoff series is about how they match up against certain segments of an opponent’s batting order—what have become known as “pockets”, as the jargon of roster-building has tried to stay more technical than its audience. When the Tigers picked Montero over Mize, they were picturing not the solid work Montero gave them to mop up a blowout Game 1 loss, but the early-game needs they faced for Game 3. They needed one of the two to be able to get out the top batters in the Cleveland order, which is no small feat, no matter who’s wedged between Steven Kwan and Jose Ramirez on a given day. Why did they like Montero better for that task than Mize?

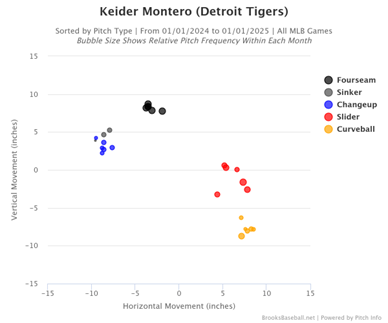

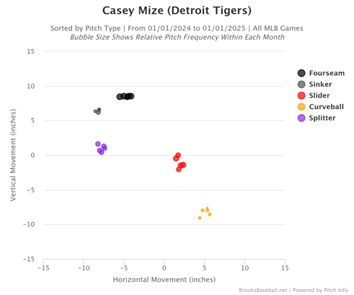

Here’s a plot of the two hurlers’ pitch movement by pitch type, from Brooks Baseball. After all, the hint they dropped to Cody Stavenhagen of The Athletic was that Montero’s edge was in pitch mix.

As you can see, there’s no big difference in their fastball shape. Mize actually threw about a tick harder than Montero did, down the stretch. It’s not about their primary heater, then. There’s a bit of something with the armside offerings they each bring; Mize has more depth with his splitter than Montero with his change, but Montero throws a heavier sinker. That sinker could have come into play, had Montero been around longer Wednesday, but it wasn’t about those pitches, either. Look at their breaking balls.

Montero’s slider and curveball each have similar depth to Mize’s, but considerably more gloveside sweep. That turns out to be important. Kwan and Kyle Manzardo both hit right-handed breaking balls with a vertical shape, particularly relative to a pitcher’s fastball, quite well. They have a harder time, somewhat paradoxically, with the type of two-plane breaker that most opposite-handed batters crave from a pitcher. In particular, both batters have struggled to get off their ‘A’ swings against that kind of pitch this year. Their good plate discipline might be working against them; they give up on the backdoor benders, then punch at it when they realize it’s creeping over the edge, or they get too anxious when they see a ball headed for the middle of the plate, then end up tying themselves in knots.

Sure enough, Montero got harmless, early contact on curveballs that bent onto the outer third of the plate against each of the first two batters he faced. He probably got lucky, more than being good, when Ramirez flew out on a first-pitch fastball, but that was it. He had carved cleanly through the first inning.

When the bullpen door swung open as the game headed to the top of the second, Vogt probably knew he was in the trap, but it was too late. He was locked in. Even though Montero had needed just six pitches to get through the first, Hinch handed the ball to Brant Hurter to start the second. Hurter hadn’t yet appeared in the series. He had debuted in the majors on Aug. 4, five days after the last regular-season meeting between Cleveland and Detroit. He only pitched in the majors 10 times before the end of the season, and no matter what the Guardians tried to tell themselves, seeing a guy in the minors—for games about the outcome of which people care much less, while working on your own game and distracted by the goal of getting the call—is not the same as seeing him in the MLB postseason.

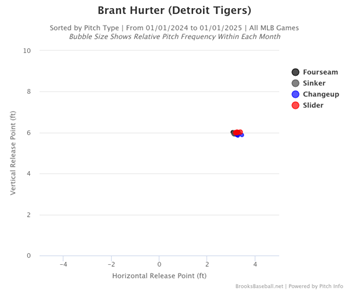

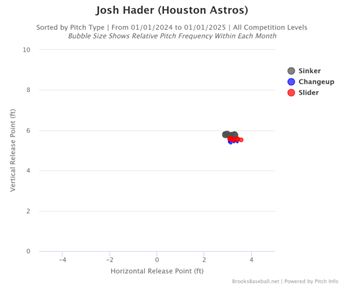

So, on marched Hurter, who is not just a tough lefty, like Tyler Holton, but a funky tough lefty. His stuff is not remotely overwhelming, but his release point is even more extreme than famously extreme release point lefty Josh Hader.

Hinch is hardly the first person to use a bait-and-switch in a playoff game, but this was a pretty wily one. Montero had the feel of a guy you’d at least take once through the order, so in addition to Manzardo, Vogt had started left-hitting outfielder Will Brennan and left-hitting catcher Bo Naylor. The latter is, arguably, the right move anyway, because even amid a rough season at the plate, Naylor brings more to the offense than does Austin Hedges. The former might actually have been Vogt trying a bit of his own strategic entrapment, because he’d surely prefer Jhonkensy Noel against any lefty to Brennan against most righties. Still, it didn’t work for Vogt. It worked like a charm for Hinch.

Hurter was the guy from whom the Tigers wanted length, and they also wanted him to force Brennan and Manzardo out of the game early. This he did, as Vogt pinch-hit Noel in the second and David Fry in the third. The visiting skipper now had the hitters he likes better in the game, but he’d spent two bench spots in almost no time, and Hinch would get to set most of the matchups the rest of the way. This game was the first time a team had used two players as pinch-hitters for non-pitchers in the first three innings of a playoff game since 1920—when it was also Cleveland, in Game 4 of the World Series, bringing on George Burns for Elmer Smith and Smoky Joe Wood (the famous pitcher, who less famously became an outfielder after his arm blew out at the end of his career) for Doc Johnston to neutralize the semi-accidental bullpenning of the Brooklyn Robins. Hinch had Vogt doing managerial gymnastics last seen under the presidency of Woodrow Wilson.

Dancing in and out of trouble in those first two frames, Hurter leaned hard into the simple advantage of his tough slot and handedness. He intentionally walked Jose Ramirez and induced an easy groundout from Josh Naylor to kill the rally in the third. Hinch let him hang around to settle down and sail through the fourth, and almost through the fifth. He got Noel to line out on a first-pitch sinker along the way. Although the sample sizes are small, Noel was a pretty safe matchup for Hurter; he struggled to deal with the angles lefties even close to as extreme as Hurter gave him this year.

The same was not true of Fry. Noel got his second look at Hurter, but Hinch denied the same privilege to Fry. With one out in the fifth, he lifted Hurter for Beau Brieske, whose simple but nasty sinker-slider combo was plenty to beat Fry and who then escaped by drawing a flyout from Ramirez. Hinch kept Brieske around to cut through the elder Naylor, Lane Thomas, and Andrés Giménez in the sixth, and then to face Noel in the seventh. Doing that required Brieske to weather two up-downs, which he hadn’t done since a low-pressure short start Aug. 9 in San Francisco, but Hinch wanted him for Noel for a reason: his changeup. Coming into Wednesday’s game, Noel had seen 23 right-on-right changeups this year. He’d whiffed on 11 of them, watched two strikes sail by, fouled off two, and mustered one soft liner for a single. Big, aggressive young sluggers often struggle with same-handed changeups. No one dared throw them that pitch on their way up the chain. They haven’t seen it enough, and their eyes get too big. It’s happened to Noel all year, when he’s run into pitchers polished and brave enough to throw him their change from the right side. In an eight-pitch encounter, Brieske threw him three changes, and once he had him in-between, he froze him for strike three with a fastball (admittedly, perhaps, a bit generously called).

That prompted a move to Sean Guenther, who was always and only going to face three batters: Bo Naylor, Bryan Rocchio, and Kwan. Unlike Hurter, Guenther is a very standard-issue lefty. He has a heavy sinker and a funky splitter with relative cut action, and he has a sweeper, but it all comes from an ordinary slot and he doesn’t throw hard. He would have been a disastrous matchup for Fry, or Noel, or Ramirez, or even Thomas. He needed to face either lefties, or fairly helpless righties. Vogt sent up Angel Martinez to pinch-hit for his catcher, depleting his bench save for Daniel Schneemann, but Martinez is unimposing, so Hinch had never worried about that. Guenther only managed to record one out, as chaos would have it, but Will Vest replaced him when Fry’s place in the order came.

Here’s where chaos still does rule, a little bit. Here’s where we have to admit that the butterflies still have their wings. Vest executed a sound gameplan. His breaking ball shapes are more like Mize’s than Montero’s, and he has no faith in his changeup against righties. There was no easy solve for him to get through the heart of the Cleveland order and record four outs; he was going to have to do it with his heaters. Of the 20 pitches he threw, 13 were four-seamers, and five were sinkers. He executed a well-laid game plan. He also got very, very lucky. With two runners on, Fry smashed a line drive that Matt Vierling just leapt and caught, making his pitcher look good in the box score. More hard contact ensued in the eighth, but Ramirez got slightly under a hard-hit fly ball and Naylor’s liner found Parker Meadows in the air. Luck can be the residue of design, but it doesn’t lose its essential character. A little bit of chaos had to bend the Tigers’ way for them to win Wednesday, or at least to win so easily.

That’s what happened, though, so in the ninth, with a three-run lead, Hinch could breezily hand things off to frequent opener Holton to close, instead. It was Holton, rather than Foley, because Giménez led off, and bringing in the lefty not only gave them the best odds not to have to deal with a leadoff runner, but to avoid any (probably useless) gambits from Vogt, whereby he might have lifted Noel or even Austin Hedges for Schneemann. Holton was ruthlessly efficient, and the game ended with a strikeout of one of the worst hitters to hold down a roster spot all season since the turn of the century.

Other than to illuminate the specific matchup-based choices made along the way and the minor intrusions of chance, I walked you through all of that so that we could see and grasp this: The Tigers scored solitary runs in the first, third, and sixth, but it probably didn’t inform their choices about pitcher usage at all. If they had scored eight runs instead, or none at all over those nine frames, I doubt Hinch would have made any different choices about when to change pitchers. That’s not really chaos. That’s an extreme kind of order.

Hinch knew that if he started with a lefty—be it Hurter, Holton, or Guenther—he’d get Fry and Noel in response, but he also guessed that those two would be stickier. Once written in, Vogt would be less likely to lift them early, so he would still have the option to flip a matchup mid-game by substituting Manzardo and/or Brennan. He even could have used Manzardo in one or two spots other than DH, and then backfilled defensively from his versatile bench. By going with a righty whom the Guardians might think would be around for a few innings, Hinch baited the hook, and once Vogt bit, the game was all in Hinch’s hands. Each pitching change was about the pocket into which that pitcher fit, and each matchup was the one the Tigers wanted, for concrete reasons we can find for ourselves, with enough statistical scavenging.

Chaos still played a role. The lack of great depth in Cleveland’s lineup still facilitated the strategy. But when we talk about chaos, we picture something messy. Game 3 was an exercise in clinical efficiency. The Tigers have brought order to a system that appears maddeningly random most of the time. Now, they just have to see how long they can pin the butterfly’s wings together.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now