Opening day 2023, first inning, two outs and a man on. Teoscar Hernández strolls up for his first at-bat for the Seattle Mariners.

Shane Bieber is on the mound for Cleveland. Hernández, the new addition, is here batting cleanup because he is a Threatening Hitter—over the preceding two seasons, he ranked among MLB’s top 25 in homers, top 30 in batting average and top 20 in slugging percentage. Bieber needs the out, but also needs to be careful.

He starts the aggressive Hernández with a tantalizing 86 mph cutter up and away. Swing and a miss.

Next, the traditional low-and-away chase slider, 85 mph with more movement. Hernández holds up this time.

Bieber tries a four-seam fastball well off the plate. Another ball.

Hernández is waiting for his pitch, but that’s the last straight fastball he’ll see. Cutter, slider, cutter runs the count to 3-2. Now that chase slider low and away is tougher to take. Bieber rips off a good one close to the corner, and Hernández is way out front. He whiffs to end the threat.

This turns out to be instructive, the beginning of something historically persistent. Those were the first three sliders in a barrage of 868 that Hernández would see across 160 games in 2023 — the most sliders any batter has faced in a single season in the pitch-tracking era (back to 2008), and most likely, the most sliders any major-league batter has ever seen in one summer.

(Note: I’m lumping sliders, sweepers, and slurves into the sliders bucket both here and throughout the article. When I reference fastballs, I’m not including cutters, which have one foot in slider country.)

It’s not surprising that someone vaulted to the top of this particular leaderboard in 2023. As slider usage surges higher and higher, it’s almost obvious enough to go by without a mention. A new frontier, though, would seem to merit some exploration. It’s not just pitchers exploring new territory by throwing the bendy pitches, but hitters experiencing new conditions while facing them.

What does seeing 868 major-league sliders in one season do to a hitter? And what can Hernández’s response show us about the road ahead?

***

The first thing to understand is why Hernández was selected, as it were, for this mission. There is a pretty solid taxonomy of hitters who wind up seeing a lot of spin.

1) Dangerous hitters: To get any sort of special treatment, the bat has to demand a baseline level of attention. Over the past three seasons Cleveland defensive specialist Myles Straw has the lowest wOBA against both fastballs and breaking balls (min. 5,000 total pitches). No one has seen a higher percentage of fastballs in that span.

Meanwhile, the previous high-water mark for sliders in a single season prior to Hernández came when Jorge Soler saw 781 in 2019, while clobbering 48 home runs for the Royals.

2) Dangerous hitters who pulverize fastballs: For obvious reasons, pitchers will take heed if a hitter is repeatedly bombing fastballs into the bleachers. Hernández is a fastball crusher. Again drawing from the last three full seasons, Hernández has baseball’s 14th-best wOBA against fastballs—a smidge better than Randy Arozarena and a tad worse than Ronald Acuña Jr. The Braves’ reigning NL MVP pulverizes everything, of course, but he is particularly unstoppable because he’s one of only four hitters who has been even better against spin than against fastballs over the past three seasons.

3) Dangerous hitters with a swing-first disposition: Sliders and their ilk are intended to induce hopeless swings, either by veering outside the barrel’s range or triggering irreparable timing mishaps. Even for major leaguers, throwing sliders over and over requires some confidence that the man standing in the box will bail you out by giving in to the urge to swing, not stand there and back you into the corner that is a 3-1 count. The hitters whose diets are still predominantly fastballs are the ones who haven’t blinked—plate discipline standout Brandon Nimmo has the widest differential between fastballs and spin over the past three seasons. Meanwhile, aggressive hitters are being fed something closer to equal parts fastball and breaking ball.

Because almost every hitter fares better against fastballs than spin, the math becomes pretty obvious for pitchers staring in at free swingers. The fewer fastballs they show them, the less likely they are to get hurt. That general heuristic works up and down the scale. Corey Seager’s “attack first, ask questions later” approach leads to a steady diet of spin, even though he does as well against those pitches as Eugenio Suárez, for example, does against fastballs.

Late in the 2023 season, as Seattle was grasping at a postseason berth and ultimately falling by the wayside, Hernández and a bevy of other Mariners hitters were having a similar problem—succumbing to the temptation of sliders. “You have to earn your fastballs in this league,” Mariners manager Scott Servais told the Seattle Times, by way of diagnosis.

Hernández has not, to this point, earned his fastballs. Over the past three seasons, only Christian Yelich has a wider split between his fastball results and breaking ball results. He manages this flaw by only swinging at 39% of spin. Hernández has swung at more than half of the breaking pitches thrown his way, roughly the same as his fastball rate. When he goes after the fastball, he’s been roughly the equivalent of Freddie Freeman. When he goes after the breaker … he’s worse than Taylor Walls.

Put it all together, and you can imagine what the dugout iPad was relaying to pitchers about to face Hernández. THROW SLIDER. RINSE. REPEAT.

***

On a rate basis, Hernández’s 2023 is not atop the list. His slider rate (32.5%) is fourth behind Hunter Renfroe last season and Nick Castellanos and Javier Baez in 2022. Baez tops the chart at 34.5%. It’s one of 40 hitter seasons in three years to surpass Soler’s 2019, which at that time set the all-time mark at 28%.

What makes the raw total interesting, though, is the concept of practice. Whether it’s the pop-science 10,000 hours rule or the image of a hitter standing in a cage tracking replicas of daunting sliders spit out by high-tech pitching machines, we are conditioned to think that seeing more sliders should make Hernández more comfortable with them, more capable at handling their challenges.

And you can find evidence of learning in Hernández’s season. It just might not be the type a hitting coach would prescribe.

Facing a barrage of low-and-away sliders, he adapted to his reality. He got better at connecting with them. He posted his lowest whiff rate against sliders since his 2020 breakout, and the second-lowest of his career behind 2019.

Whether out of improved confidence or a sense of necessity, of inevitability, Hernández also swung at more of those chase sliders, a career-high 41.3% of them. Prior to 2023, he had ended 188 plate appearances in the majors on sliders out of the zone, collecting a total of nine hits. In 2023, he tallied 13 hits in 88 plate appearances that ended on them, including two doubles and, in September, his first career homer on a chase slider.

To make that happen, though, he was making sacrifices. Subconsciously, or maybe sometimes purposefully, Hernández was training his eyes and his bat for a slider when he still had the strategic license to focus on fastballs.

The result was exactly what the pitchers were going for, really. Improvement squaring up sliders meant that 17.8% of his swings at them led to fly balls or line drives—the most productive type of contact. Against fastballs, however, a career-low 14.5% of his swings turned into fly balls or line drives. The good slider swings gave him a .410 average and .699 slugging percentage, but the fastball ones came with a .588 average and 1.325 slugging percentage.

Look at the tally for Hernández’s air-ball swings at ended at-bats:

- 2021: Fastball 105, slider 50

- 2022: Fastball 89, slider 32

- 2023: Slider 86, fastball 81

Pitchers will take that trade all day. And generally, they are. MLB hitters as a whole are playing out a version of the Hernández arc—seeing more hard spinning pitches, making modest improvements against them, and remaining relatively stagnant on the dwindling number of fastballs they do see. His extreme experience is already becoming common, and soon enough it will be universal.

***

Hernández’s overall results dipped like a sharp slider in 2023, his last season under team control. After batting .283/.333/.519 over the three-season span from 2020-22, he scuffled to a .258/.305/.435 season in Seattle.

We should note here that T-Mobile Park’s unfavorable hitting conditions probably had some effects in here that are hard to parse. Hernández also said recently that he found it difficult to see the ball well at T-Mobile Park. He even good-naturedly responded to a Mariners fan who summed up the difficulties this article outlines with a meme.

In free agency, he took a one-year deal with the Los Angeles Dodgers, where he can slot into a shadowier spot in a thunderous lineup and perhaps reclaim his previous form.

While we’ve never seen anyone respond to quite this many sliders, we have seen some contemporaries reverse the trend. In 2022, the Phillies’ Castellanos, you may recall, saw an even higher percentage of sliders than Hernández did in 2023. Last season, though, he was a top 10 hitter in baseball against them. He didn’t stop swinging at them, didn’t try to change his nature.

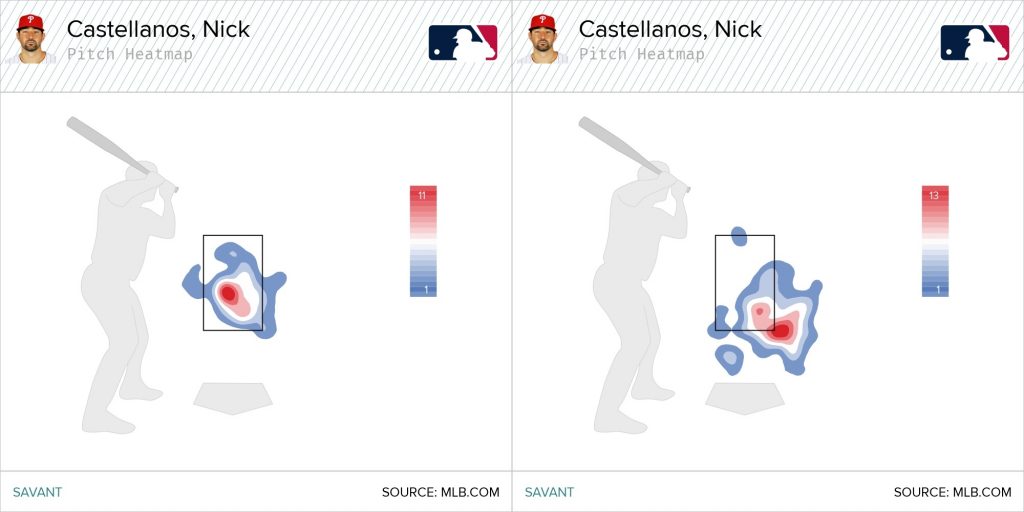

Instead, as relayed by Matt Gelb in The Athletic, Castellanos made an adjustment with the assistance of hitting coach Kevin Long, stepping closer to the plate to change how Castellanos viewed low and away pitches. Instead of weakly hitting into a lot of outs, he swung and missed a ton — the second-highest whiff rate on sliders in baseball. That sounds bad, but unlearning the habit of making contact with the classic down-and-away slider was a good thing. Compare the sliders Castellanos put in play in 2023 (on the left) with the ones on which he whiffed (on the right). Obviously, whiffing in two-strike counts is bad, but any other time, it’s preferable.

A boom or bust approach kept more at-bats alive and signaled that Castellanos was still taking his best swings at sliders, keeping his brain in the mode to hit fastballs. When he did connect with sliders, he did damage, whacking an MLB-best 15 of them over the fence.

Now, maybe that case study will prove helpful as a guide for Hernández, a talented slugger with a similar profile. But it won’t stop more and more top-level hitters from running headlong into this steep learning curve.

What Teoscar Hernández saw in 2023 was something like the future of pitching. And if there’s a lesson from his experience, it might be to learn less, to reframe the problem instead of trying to solve it. Don’t adjust to the insistent, repeated drumbeat of sliders. Stop and try to make the drumbeat adjust to you.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now