This article was originally published on July 22, 2024.

In 1845, Sir John Franklin set out on an ambitious, ultimately foolish expedition to try to connect the Northwest Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, in what was believed to become a triumph for the British Empire. The Northwest Passage had long lived as a mythical gateway to untold riches. But like so many other ventures of the late British Empire, this one stretched it thin and ended not just fruitlessly, but with every crew member lost to the great white north.

Before his final ill-fated attempt, Franklin’s first undertaking in the New World was the Coppermine Expedition, charting the north coast of Canada. He got the assignment thanks to his time in the Royal Navy. His father had gotten him that appointment.

“With elements of both horror and sheer incompetence,” Franklin lost 11 of his 22 men on the Coppermine Expedition—mostly to starvation, though there were accusations of both murder and cannibalism—largely due to poor planning for the hazards and obstacles of the journey ahead. Despite being understood to be a buffoon by those he encountered along his travels, he was lauded back at home in England upon his return. His men, so driven by hunger to desperation, at one point attempted to eat their own leather boots. This led to Franklin himself being adorned with the nickname, “the man who ate his boots.” Somehow this failure, and moniker, failed to hinder his future opportunities.

***

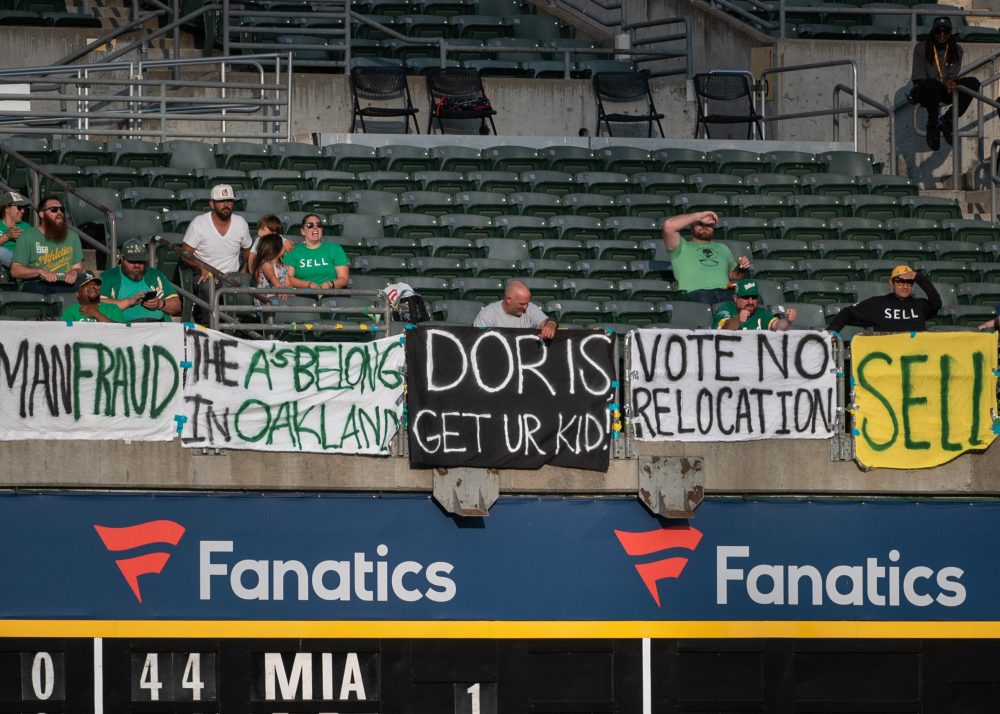

In 2024, another ill-fated John F. has embarked on his own foolhardy destination toward a glittering ambition. John Fisher, owner of the Oakland Athletics, has spent the past few seasons poisoning the well in his team’s hometown to help better facilitate a move to Las Vegas, a city naturally inhospitable to and largely disinterested in baseball. Fisher’s resolve, despite these glaring warning signs, has led to him running himself out of town and up the California Delta to Sacramento, where the Athletics are set to play at least three seasons before, allegedly, actually moving to Las Vegas.

While the groundwork has been laid for a new stadium to be built, the land parcel allocated for it appears, by all measures, to be too small for the acreage required for a roofed ballpark, a necessity in the Southern Nevada desert. There is also the matter of the billion dollars of funding that Fisher apparently needs to actually build the thing which, to date, has not yet materialized.

The longer the saga has drawn on, the more clear it has become that an A’s move to Sacramento—much less eventually, supposedly, to Las Vegas—is bad for literally everyone else involved.

It’s very clearly bad for the players, both the A’s and their opponents. Rather than traveling into and staying in San Francisco, a world-class city across the bridge from Oakland, teams will travel to Sacramento, a city unprepared to offer the basic workplace amenities of major-league baseball. They will play under substandard playing conditions for the major-league level, with detached batting cages and clubhouses located out beyond the outfield wall.

They will also routinely play in triple-digit heat. Despite being farther north than Oakland, in 2022, Sacramento topped 100 degrees 41 times—all during baseball season, of course—and there’s a good chance they’ll smash that record in this record-setting summer. And with the wear and tear of more than 150 major and minor league games being played on the surface (remember that an ACTUAL Triple-A team still plays there), the plan is to switch to artificial turf. Beyond the added injury risk of turf, which the NFLPA recently highlighted, studies have found that artificial surfaces can range from 140-170 degrees under hot, sunny weather conditions, the kind that Sacramento provides all summer long.

We know the situation is bad for the fans of Oakland. But it’s also a mess for any potential fans in both Sacramento and Las Vegas. As has been confirmed through last week’s schedule release, they aren’t even affiliating themselves with the city of Sacramento for their time there, simply going at “The Athletics” (or ATH, on your team of choice’s fridge magnet schedule). They’re also trying to play nearly 10% of their “home” games away from Las Vegas, volunteering themselves to become the Jacksonville Jaguars of MLB.

But what’s most wild about this whole debacle is that it is also bad for the owners. Not only does the move leave the A’s as a revenue share taker for certain as long as they’re in limbo, and almost certainly for the long haul, but each of the other franchises forfeited their share of the roughly $300 million relocation fee that Rob Manfred mysteriously decided to waive. That’s $10+ million cost, per owner, up front. Then there’s the reputational damage of a constant stream of negative press from not only the bungling of the entire endeavor in Oakland, but of Fisher’s inability to get the funding he needs to even begin construction in Vegas. You don’t think the banks looking at the plans and passing because they see Major League Baseball as a losing bet hurts everyone?

All this while baseball has its eyes on expansion, and while Las Vegas is one on a short list of potential markets it is considering. This fiasco has allowed Fisher’s bumblings—with Manfred’s full-throated support—to block that market from a nice, clean start, free of all his drama, further limiting MLB’s options.

And now, finally, a question asked over and over these past few years by voices all over the sports world, seems to have an answer: Why haven’t any of the deep-pocketed, clearly interested potential ownership groups in the Bay Area stepped up to buy the A’s and keep them in Oakland, building them a new stadium there? Because Rob Manfred not only won’t let them, he won’t even let them talk about it, without fear of being blackballed from the league.

According to Scott Ostler of the San Francisco Chronicle, Manfred has issued a gag order on prospective buyers trying to offer both he and Fisher a lifeline out of the Charybdis of their own making. But instead of taking it, they’ve tied themselves together and not simply rebuked the offer, but threatened people—with motivation to buy; with deeper pockets than Fisher; with history of successful professional sports team ownership and stewardship; with designs on preserving a great, historic baseball market—with mafia-style tactics. It’s worth seeing the full context of Ostler’s observations:

The Chronicle’s John Shea, who annually peppers the baseball commissioner with questions about the A’s and Oakland, asked Manfred on Tuesday if a mayoral change in Oakland would make a difference for the city’s hopes of keeping the A’s if the Las Vegas deal falls apart, or for future expansion to the city.

“Look,” Manfred said, “our Oakland decisions have been made. What happens in Oakland is between the citizens of Oakland and their elected officials.”

Oh? Why is it, then, that various Bay Area groups interested in buying the A’s and keeping them in Oakland, or bringing an expansion team to Oakland, have been warned to keep quiet about their interest or risk being crossed off the list of potential buyers?

That warning has come to prospective buyers from Oakland officials, who say they have tried to get MLB to lift that gag order so the world can know that there are folks with money who believe in Oakland as an MLB city.

Could it be that MLB is worried that a local potential buyer who publicly expresses interest in such a project in Oakland would make Fisher and Manfred look foolish?

All of this is good for the game, how, exactly? Who, exactly, is benefitting from this arrangement, other than, potentially, Fisher? How does any of this help Major League Baseball, beyond Manfred possibly saving some measure of his own face, after it gets scraped across the California desert? Put another way: If you were one of the other 29 owners, and the commissioner was insisting on a plan that both costs you money and keeps you from making more, drags your name through the mud for going along with it, and is blocking a better potential owner from stepping in and solving everything in a way that benefits the entire sport, why wouldn’t you pull the plug on this entire operation, the commissioner himself included?

As we’re often reminded, anytime baseball makes a decision that’s bad for the players or fans, but good for ownership, Rob Manfred works for the 30 team owners. He’s their representative. If he doubles, and triples, and quadruples down on a plan that is potentially good for one owner, but clearly and obviously bad for the other 29, who is he even representing anymore?

***

On his slapstick Coppermine Expedition, John Franklin was in the midst of trying to convince Akaitcho, chief of the Yellowknives, who he had enlisted for help, why the Northwest Passage was so valuable and important. Akaitcho asked in return why, if it was so important, had it not yet been discovered. Franklin had no good answer.

And yet, he plodded on, returning to the same quest to find the Northwest Passage once again, long after it was clear he should have reconsidered. This was Franklin as described by Anthony Brandt, author of The Man Who Ate His Boots, as he embarked on his fateful, final journey, some 26 years after Coppermine:

“He was the last choice. He was 59 years old. He had no business doing this again but he was trying to save his reputation.”

Franklin’s Northwest Passage mission ended before it could ever truly begin, when his ships became locked in ice, first for one winter, then for another full year. When it became clear the mission could not succeed—even with a three-year supply of provisions to get the men through—everything fell apart. Franklin had already died by the time his cohorts devolved to the inevitability of cannibalism.

One wonders if, at some point when turning back was still an option, the crew knew that the folly of one man would lead to them eating each other alive.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now