Blaming Derek Jeter for various things has become rather passe. We all had our fun tearing him down over the years. But his playing days are long over now. Jeter is a broadcaster these days, stuck in his own personal purgatory with frenemy Alex Rodriguez. Derek Jeter cannot hurt us anymore.

And yet…his actions on September 15, 2010 changed everything.

St. Petersburg, Florida. Yankees-Rays. One out, top of the seventh, down one, Jeter in the batter’s box. Chad Qualls on the mound. Qualls throws the baseball 91 miles per hour. It hits Jeter’s bat. The sound of a baseball making contact with a bat is unmistakable. Jeter pretends the ball hit his hand. The home plate umpire believes him.

New York’s athletic trainer joins the act, checking on the shortstop, making sure his hand is still healthy enough to keep playing the sport, that the bones beneath his unblemished skin have not been liquified.

Rays manager Joe Maddon insists that Jeter was not hit by the pitch. He is right. He is then right fairly loudly. The umpire is unmoved and ejects Maddon from the premises. Jeter is awarded first base.

There was a lot of talk over the following days that can essentially be summed up as an unanswerable pair of questions: Was Derek Jeter cheating? Was it gamesmanship? What was seemingly lost in the shuffle was the question of why instant replay still did not exist in Major League Baseball, aside from suspected home runs. It was 2010 already.

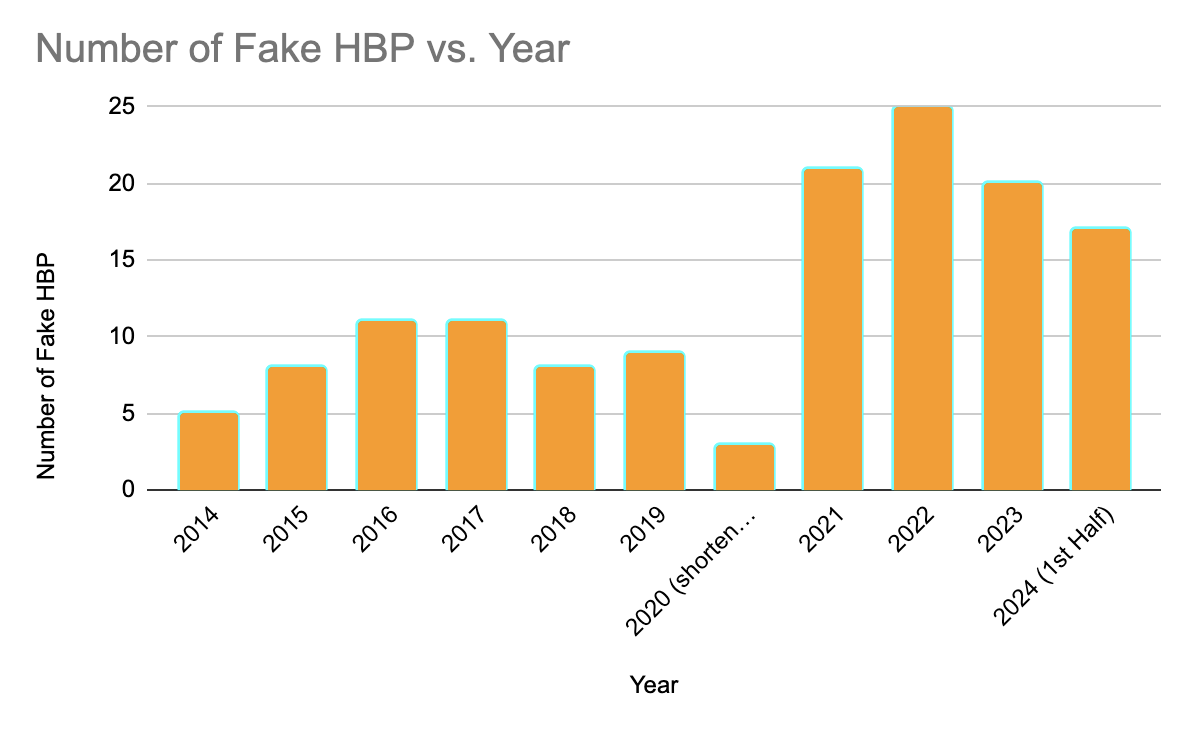

Expanded replay would not make its way to the big leagues for another four years. From the time it reared its head in 2014 through this year’s All-Star Break, how many times do you think a batter was incorrectly ruled to have been hit by a pitch, only for league headquarters to take a peek or two and conclude the truth? Hint: the number is much bigger than what you’re thinking.

138 times.

And it’s only happening more and more.

How could this be? Is it really so hard to figure out who is faking and who isn’t? Let’s try this: I’m going to show you a bunch of batters. They will all be awarded first base by the home plate umpire. Which of them actually got plunked and which did not?

The answer: They were all faking it. 100 percent fabrication. Liars, the lot of them. Not a single ballplayer was injured during the making of that supercut. Unless you count the stinging on the hands that lasts for a few seconds when the ball makes contact with the knob of the bat, and you shouldn’t.

This fascinates me. Players are fully aware that every manager has access to a creature lurking in the bowels of the stadium that watches everything and lets them know when to challenge a call. They know the umpires will then put on headsets and wait for as long as humanly possible to hear a disembodied voice from New York City tell them if their eyes just lied to them or not. So why do this? Don’t you want another shot at getting a hit?

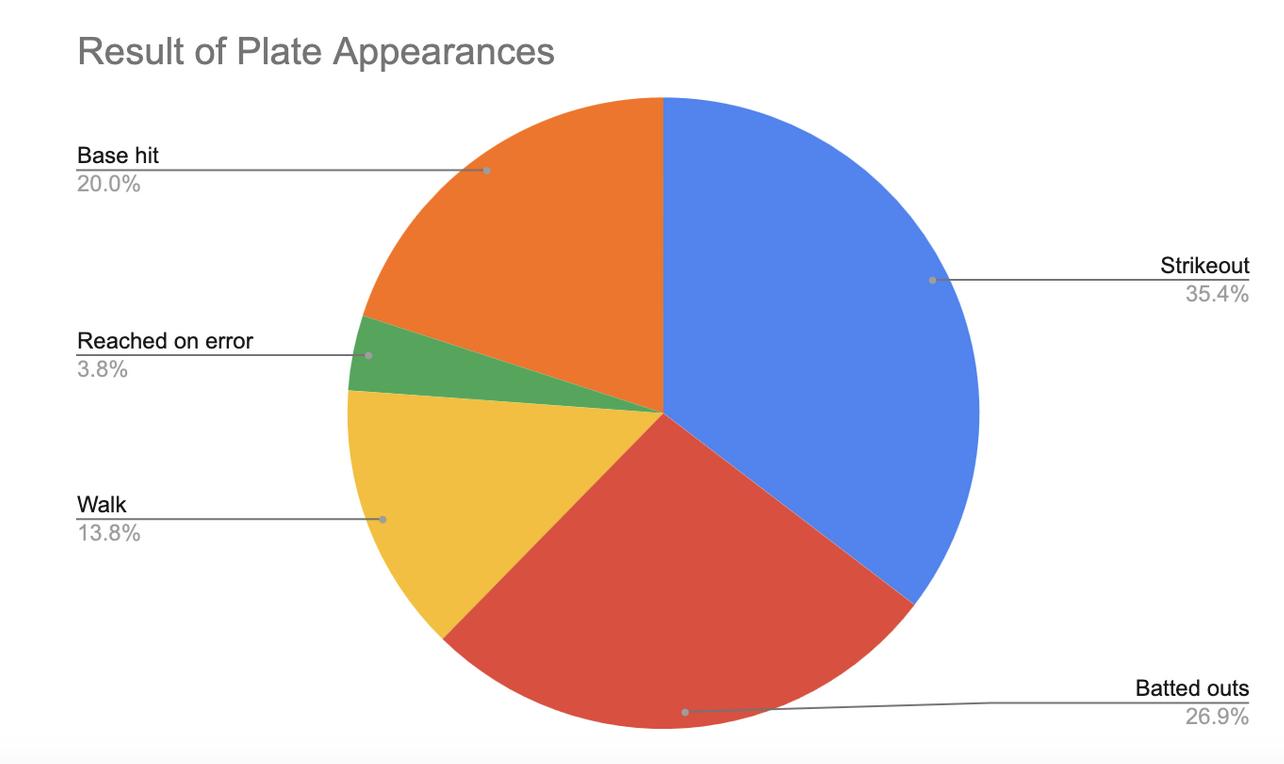

I then wondered if pitchers gained an advantage when this happens. If batters are so desperate to get on first base without hitting the ball, they must not have any confidence in themselves. I looked at what happened at the conclusion of the 138 plate appearances.

Batters ended up on base 37.6% of the time. That’s really good, considering a fair number of them had to deal with a two-strike count after the hit-by-pitch call was overturned. Three players actually homered. It turns out a guy capable of nearly hitting you on one pitch might not be scraping the black on the other ones.

So okay, there goes that theory. But it just raises the question again of why batters wildly dramatize any ouchies in the first place.

In order to understand, perhaps it’s best to look at how these performances play out. The very first time a hit by pitch was reviewed on replay and overturned was on May 1, 2014 in Baltimore. The Pirates were in town, and Tony Sanchez was up to bat. Bud Norris threw a baseball that hit Sanchez’s bat.

The umpire thought it hit Sanchez. The batter stood around home plate for a while. Give him credit for not pretending he was injured. Maybe his brain already sent the message to the rest of his body that instant replay was going to show the truth anyway, so why bother?

Sanchez was ordered to go to first base. He did as he was told. It was there that a smile crossed his lips while talking to his first base coach.

It’s the smirk of a man who knows what is about to happen. The enemy crowd knows what is going to happen too, because they show the replays on the stadium big screens. The television audience knows what’s going to happen also. Only the umpires are in the dark. Sanchez is already mentally preparing to walk back the 90 feet he just traversed.

The umpire takes off his headset. He puts up his hands and points to Sanchez. He’s telling him to come on back. The next time we see Sanchez, he’s putting his equipment back on.

There is a pattern that emerges more often than not. Some, if not all of the following, take place:

Act 1: The Deception

Act 2: The Awkward Walk to First Base

Act 3: The Smirk/Smile at First Base

Act 4: The Awkward Walk Back to Home Plate (While Smiling)

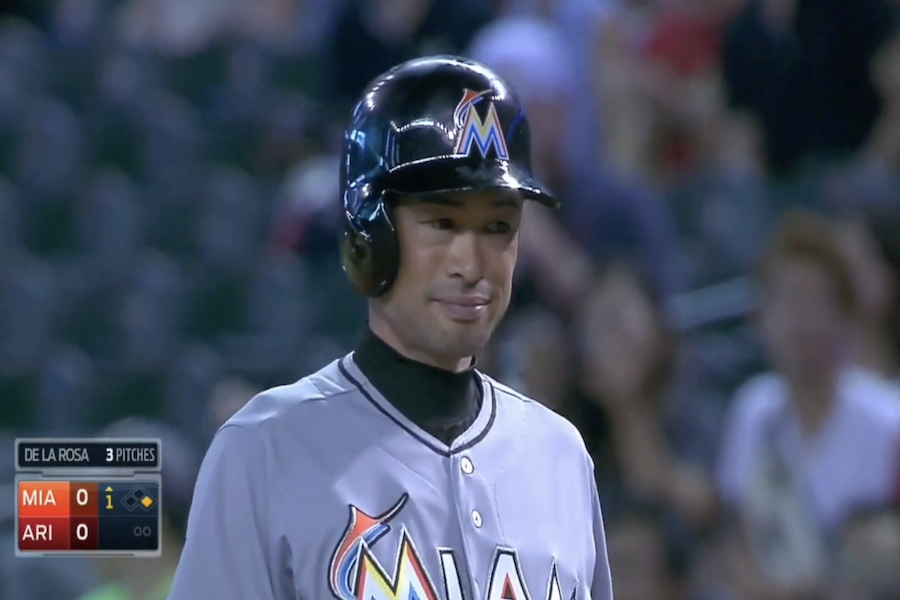

Even the great Ichiro was once guilty of this. Leading off for the Marlins against the Diamondbacks on July 20, 2015, Rubby De La Rosa threw a pitch that made contact with Suzuki’s bat. Ichiro crumbled to the ground.

That part is understandable—the ball was heading towards his front shoulder, and the crumbling was already in progress on contact. But then he keeps looking at his wrist. And looking and looking. The Diamondbacks challenged. Ichiro continues to look at his wrist, but he can’t help himself—he smiles.

The umpire calls for him to return from whence he came. He looks up, says “What?”, and you think he might argue. Instead, he smiles on his way back to home plate.

That’s the thing: I’ve never seen anyone argue after the call was made.

Jean Segura has tried to feign pain more than anyone. He’s done it four times. The first time was on June 6, 2015 as a Milwaukee Brewer.

He even pulled a Jeter and got the trainer involved.

The second time was almost exactly one year later, on May 28, 2016. This time as an Arizona Diamondback.

The team trainer came out again. Segura pointed at the part of the helmet where, according to him and him alone, the untamed baseball made contact.

No dice. So Segura was once again made to walk the walk of shame.

The deception was in such bad taste that Padres color analyst Mark Grant said Segura should be given a red card. But Segura was undaunted. He tried to get away with it yet again the following year when he was a Seattle Mariner. Perhaps he figured that if he kept switching teams, umpires wouldn’t recognize him?

Five years passed. A lot can happen to a man in five years. Some new faces emerge. Some go away. You learn a lot. And yet Jean Segura did not learn enough. On August 22, 2022, the now-Philadelphia Phillie thought he caught a break. Reds catcher Austin Romine got hit in the groin area.

While Romine was in actual pain, Segura slinked off to first base. Unfortunately for him, Reds manager David Bell managed to multi-task and challenged the hit-by-pitch call while making sure Romine was okay.

Segura knew he was busted. He allowed himself to laugh at whatever Joey Votto was telling him. There’s a good chance Votto was commenting on what he just saw on the jumbotron, that Segura is guilty once again.

He retreated back to home plate quietly.

There are exceptions. Every so often, it makes sense to pretend you got hit by a pitch. Allow Mike Trout to demonstrate.

June 20, 2016. Minute Maid Park: Trout accidentally grounds out to end the top of the third inning. Or did he?

He did. The ball hit the knob of the bat and rolled fair. But he would prefer that he didn’t, so it’s acting time. He lets pitcher Doug Fister apologize for throwing inside. Then, standing on first, he insists to his dugout that it hit his hand, lest there are people watching.

Then he sees the replay on the gigantic screen at the ballpark. He looks puzzled. How do I get out of this lie?

Busted. All he can do now is laugh. Say he’s strong. It was worth a try.

Another instance where it makes sense to fake it on the off chance you make it is if the bases are loaded in the bottom of the ninth and the game is tied. José Abreu had that opportunity in 2022.

This is the most badass way to pretend you got hit by a pitch possible. Abreu calmly raised his hand to the home plate umpire to indicate he was just beaned, turned around and kept his hand raised towards his teammates, turning the gesture into one of triumph.

The White Sox celebrated their victory. Abreu successfully avoided a cold shower.

Fireworks went off. A night well spent. Except, the pesky Minnesota Twins challenged the call, because they had nothing to lose. They were right to do so. Abreu was sent back to home plate. He won the game on a fielder’s choice two pitches later. Not nearly as cool, but it’ll do.

At this point you might be wondering what the hell is it I expect batters to do when they’re told to go to first base: not go?

Well, yeah.

On May 31, 2016, Evan Longoria was not hit by a pitch. The umpire told him to go to first base. He did as he was told.

But Longoria understood something virtually nobody else seemed to. That he was free to leave first base almost as soon as he got there. Specifically, it was the second he saw that Royals manager Ned Yost was going to leave the dugout and ask for the play to be reviewed.

With a smile and a shrug, Longoria single-handedly sped up the whole drawn-out process. By the time New York figured out what Longoria had known minutes before, he was waiting to get going. He was waiting to try to get a hit. Because he’s a hitter.

Three and a half weeks later, it happened again. Longoria was not hit by a baseball.

He was told to go to first. Rays manager Kevin Cash told Longoria the same thing. But Longoria wants to hit. He’s a hitter. “It hit the knob of the bat,” he freely admitted.

He followed the letter of the law, if not the spirit. Longoria hung out at first base for a few seconds, saw Buck Showalter prepare to ask for a review, and said deuces to Chris Davis.

On the opposite end of the courtesy spectrum, there was Aaron Hicks. Hicks had the temerity to ask for a review when he thought he wasn’t going to be awarded with a free pass, despite knowing full well the baseball didn’t make contact with him.

This isn’t 2010. Times have changed. The Yankee does not get the benefit of the doubt anymore.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now