Thomas Jefferson wasn’t only the primary author of the Declaration of Independence; he also wrote a book. From the title, Notes on the State of Virginia (1785) sounds like a traveler’s guide. In some senses it is that, but Jefferson also provided his thoughts on a number of other topics, including his justifications for white supremacy. Perhaps no traveler’s guide is complete without an explanation and defense of the form the society one is visiting has taken; depending on the answers, you might want to keep your passport handy and your go-bag by the door, or maybe not visit at all.

Virginia was a slave state. This is a retroactive distinction that had no meaning then because the United States was a slave country. At the time, there were more slaves in New York than there were in many southern places. Given that, Jefferson shouldn’t have felt the need to defend the system; white supremacy, with or without slavery, was just the way things were in the nation. Yet, abolition was also everywhere, and not just in Europe and in the North, but in Virginia too. That notion lasted until about 1800, when a combination of Gabriel’s Rebellion and the Haitian Revolution frightened slaveholders into believing that Black people could never be freed lest white people be murdered in their beds. This was the basis for Jefferson’s oft-quoted line about slavery, “We have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go.”

That was in the future when Jefferson wrote Notes, but he couldn’t have freed his slaves even if he had been inclined to do so (he wasn’t); too much of his personal economy was tied up in human chattel. Perhaps for that reason, the section of Notes trying to justify holding Black people in bondage sounds especially shrill today, and not just because we have—at least until recently—been taught to recoil from naked bigotry. The noise we hear as we read are the gears of Jefferson’s mind overheating: he was both a slaveholder and a highly intelligent man who was capable of empathy. These qualities are not compatible.

Having begun, Jefferson had to force himself through the issue for his own reassurance if not for his readers’ edification. He had to show that these obvious humans—obvious enough that he had been raping one on an ongoing basis—were so backwards, primitive, and helpless that the only purpose for which they were fit was to be held in perpetual bondage. And so he told himself a story about those people and their more evolved racial betters so he didn’t have to confront the incoherence of his own beliefs.

We will not quote that story here. It would foul the pages. That isn’t to deny that Jefferson said and wrote many things that are worth quoting. If you visit his monument in Washington you will see one of his most inspiring lines inscribed on the inner ring of the dome: “I have sworn upon the altar of god eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.” The tragic irony (and not just for him, but for so many Americans he influenced politically and morally, or simply owned, including his own children) is that his mind was as much a victim of tyranny as any other’s, held in thrall by the self-justifying hallucinations of the bigot.

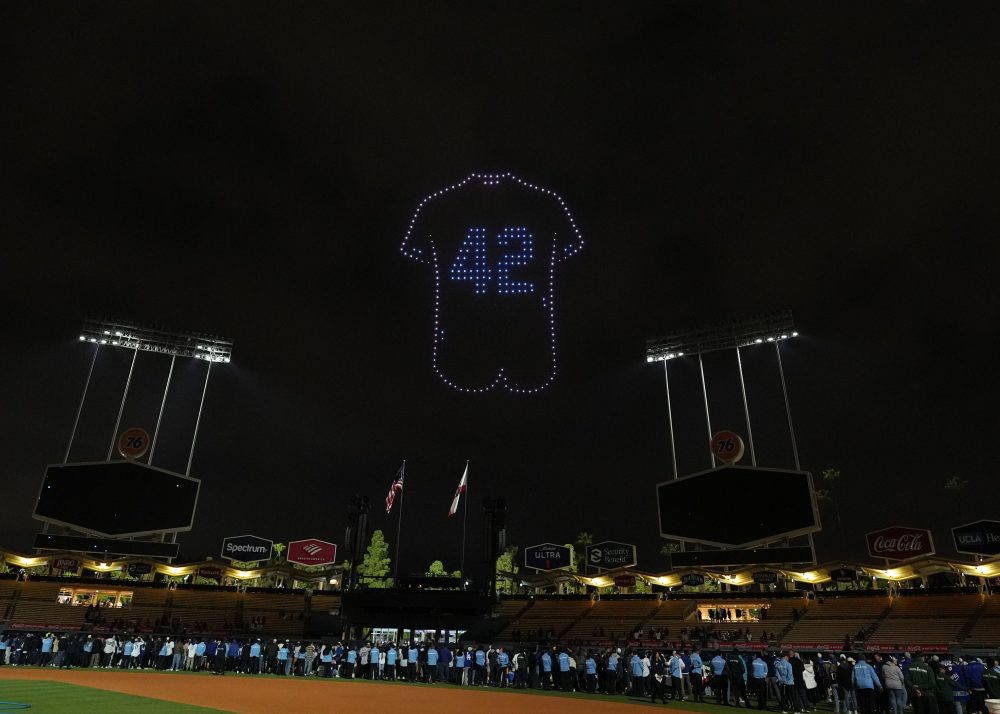

Jackie Robinson will forever be one of the greatest of Americans because he refuted those hallucinations. He never should have had to do it, and even if someone did have to, it shouldn’t have had to wait until as recently as 1947. For over 70 years the country had been frozen, held in a time-warp by yet another set of contradictions: The freeing of the slaves, the granting of full citizenship and voting rights to those former slaves, and the fervid desire of a large part of the white polity to deny them those rights and continue the old racial social structure by other means. They used laws, they used the courts, and they used guns and fire and nooses, but before resorting to all of that, they used their greatest weapon. It was composed of two one-syllable words: THEY CAN’T.

The THEY CAN’T construction was something along the lines of, “Oh, sure, in an ideal world all people would be treated equal, like old Mr. Jefferson said, but it isn’t really possible, because they’re like children, really, and THEY CAN’T do [a long list of things whites did on a daily basis from the basic to the extremely complex to baseball].” This was said so often that a lot of people believed it—and those people weren’t as well-read or inquisitive as Jefferson, so they believed it not as a salve to their doubts but as a license for cruelty. Look for them in the corners of the unforgivable souvenir postcards of lynchings. You’ll find them leering out at the camera, getting off on the sadism.

Science came along for the ride as did religion, which found the Biblical story of our Edenic origins was not easily adaptable to a world in which not everyone looked like Adam and Eve as painted by Titian. And so both scientists, and also “scientists,” and the theologians, and also “theologians,” made up some stories of their own to explain why it was right for the pale pink people to hold the brown people hostage, or at the very least make them get the hell off the sidewalk when a white person strolled by. Then the historians jumped onboard and said that emancipation had been a bad idea and that Black Americans had instantly proved THEY CAN’T participate in the political system, and D.W. Griffith made the first blockbuster depicting just how ugly things were because of their incapability.

And so there was a kind of convergence of every field of inquiry and the arts that the way things had been for white and Black people was the way that they should be, and where they had changed they should go back to the way they were. Belief stuck that way for quite a long time, and whenever it hinted at loosening up a little there were also those aforementioned guns. This made Americans the most hypocritical people on the planet. The gap between our rhetoric and our actions could be seen from space from day one, hence Samuel Johnson‘s famous quip asking why it was “that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?”

Throughout, there were always some Americans to whom the whole situation was morally abhorrent. Branch Rickey was one of them. He was also self-interested, wanting to open up new lines of talent for the chronically underfunded Dodgers. It doesn’t matter; sometimes mitzvahs, like murders, require the motive, means, and opportunity to reach fruition. Rickey was also an expert in his field, which was not morality but scouting ballplayers. Just as he could look at a Joe Medwick, Dizzy Dean, or Pepper Martin and know he had seen talent, all he had to do was take in a Kansas City Monarchs or Pittsburgh Crawfords game to understand that THEY CAN’T was a lie.

Here Rickey might have encountered more of a problem within the game than he actually did: when the baseball establishment fought him on integration, when individual players fought him, they largely didn’t do so on a THEY CAN’T basis. To use a phrase from our time, game recognizes game and for most of them it must have seemed implausible to even try to push a “But Satchel Paige really isn’t that good” narrative—not that it didn’t stop a few from trying. Mostly, though, they kicked on a political/economic/social basis, mumbling words along the lines of, “Our fans don’t want to associate with them, our players can’t or won’t associate with them, we don’t want to associate with them, and so even if THEY CAN, the reality is THEY CAN’T because they would be bad for business and clubhouse comity.” As The Sporting News editorialized in 1942, “the leaders of both [white and Black baseball] groups know their crowd psychology and do not care to run the risk of damaging their own game.”

Note that once Rickey, having ignored this line of attack, went forward and Robinson arrived, the most reactionary bigots, like Ben Chapman, moved the goalposts and attacked Robinson not on the basis of skill, but identity and, when that had no effect, attempted to rile Robinson’s white teammates with some of the oldest calumnies about Black lasciviousness as it applied to their wives and girlfriends.

Until this week it would have seemed unnecessary to affirm here that THEY CAN’T couldn’t stand up to what happened on the field. Robinson could. Roy Campanella could. Larry Doby and Satchel Paige and Monte Irvin could, and onwards: Rickey and Ozzie and Winnie could, right down to the present day. And the lie fell away for those across the oceans, too: Minnie Miñoso could; Roberto Clemente sure as hell could, and so too could Luis Tiant, Tony Perez, Tony Oliva, and the brothers Alou.

Then the truth of Robinson rippled outwards across the years and miles and made global baseball possible. There would have been no Ichiro, there would be no Ohtani, without Robinson. He and those who followed him made their participation thinkable. After Robinson, one could still “but actually” Jefferson’s “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal” to death—that started pretty much the moment his quill hit parchment—but here, both on the field and the back of the baseball card, was a perfect example of those words being absolutely, perfectly, irrefutably correct.

Except for one thing: those self-justifying hallucinations are not susceptible to evidence. We were reminded of that again this week when we learned that the Department of Defense had deleted (in some cases temporarily) a series of web pages dedicated to distinguished alumni of the military services who happened not to be white—among them Black Medal of Honor winners, the Tuskegee Airmen, Native American Code Talkers, and an African American officer from California named Jackie Robinson, unjustly court-martialed for refusing to move to the back of a segregated bus. As of March 18, Robinson’s page delivered a 404-Page Not Found error. The page’s URL had been edited to include the phrase “deisports.” Your tax dollars at work.

As you almost certainly know by now, “DEI” stands for “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.” The original idea behind that trio of words, whether applied to government or private enterprise, was, “Let’s make our jobs available to all different kinds of people; let’s make sure they’re all treated the same way; let’s make sure that they all feel an equal part of the whole.” Each Christmas we hear failed Angels owner Gene Autry sing, “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” with the verse

All of the other reindeer

Used to laugh and call him names

They never let poor Rudolph

Join in any reindeer games

This is precisely what DEI was meant to address:

- We should make sure all types of reindeer, such as Rudolph, are aware of and able to apply for open positions; Team Reindeer can then benefit from members—all qualified—having a wide variety of backgrounds, life experiences, and perspectives. (Diversity)

- Do not laugh at Rudolph and call him names. As a member of Team Reindeer, Rudolph is entitled to the same treatment as every other member. Team Reindeer members are more productive when they are not mocked or shamed as part of their Team Reindeer experience. (Equity)

- As a Team Reindeer member, Rudolph should feel welcome to participate in any reindeer games. Team Reindeer cohesion is harmed when members are excluded from activities on the basis of their appearance, sexual identity, etc. Once you’re on Team Reindeer you’re on Team Reindeer. (Inclusion)

These ideas are not terribly complicated, but recently the racist right has repurposed the term as a slur. To dismiss a person as a “DEI hire” is to say that no matter their level of accomplishment they were only in a position to do those things due to some special characteristic. They are unqualified; what they have is unearned. It is the old, reflexive THEY CAN’T staged in modern dress, an unthinking generalization meant to invalidate, in particular, people of color. What was, last summer, applied to sitting vice-president Kamala Harris (a former state attorney general and United States Senator) has now been applied to Jackie Robinson.

No one should be dismissed on this basis, but to have the federal government do this to Robinson is especially appalling given his obvious, irrefutable achievements and his importance to American societal progress as a whole; he began at the major league level more than seven years before a version of the Supreme Court that now seems impossible said, “Separate isn’t equal, duh.” As Red Smith wrote in December 1956, “His arrival in Brooklyn was a turning point in the history and character of the game; it may not be stretching things to say it was a turning point in the history of the country.”

And yet, that this has been done to his memory—and it was done; despite the restoration of Robinson’s page he has still been slurred by, again, the government of the United States—shouldn’t be surprising. There is no bottom to the racist mindset, no level to which it will not sink in affirmation of its delusions. Robinson’s DoD page wasn’t exactly his plaque at Cooperstown, and almost certainly not the first place anyone looking to learn about him would go, but they had to deny the worth of a Black American anywhere within their reach.

THEY CAN’T self-hypnotists are very good at denial. Go back to Jefferson. He was confronted with the poetry of Phillis Wheatley, a former slave. Jefferson said: Blacks are incapable of poetry; Wheatley’s verses were “below the dignity of criticism,” which is to say so bad as to be unworthy of comment. He was confronted with the achievements of Benjamin Banneker, a Black writer, surveyor, and mathematician. Jefferson said: Not bad, but a white guy must have helped him.

Baseball wasn’t too different. When Rickey made his plans public, some players and front-office types said there were no players of major league quality in the Negro Leagues, or maybe one; Bob Feller was willing to stretch as far as two. They said that Black players would not be able to withstand racist heckling from the stands and disdainful treatment by their teammates, especially in the South. New York Daily News columnist Jimmy Powers (who had proved himself an Olympic-level idiot long before 1945) wrote that “If a Negro player couldn’t muscle into major league lineups” during the war “when 43-year-old outfielders patrolled the grass… and one-armed men and callow 4Fs were stumbling around, he won’t make it in 1946 when the rosters will be bursting with returned headliners.” Not that Negro Leaguers had been allowed to try, but nevertheless, Powers was saying, they had already proved that THEY CAN’T.

When this approach didn’t deflect Rickey and Robinson, pro-segregationists shifted to pure obstinacy. When Robinson tried out for the Red Sox, someone shouted, “Get those Ns off the field,” which meant, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, you’re not even entitled to be here.” When Robinson first came to St. Louis in 1947, the Cardinals (using the tactic Cap Anson had wielded against Fleet Walker) threatened to strike. When Pinky Higgins was manager and then general manager of the Red Sox, he said an “N” would never be a member of the team as long as he had something to say about it. This was like Governor George Wallace of Alabama saying (not too long after), “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

In all cases, why? If you had asked, the answers would have varied, but it seems reasonable to infer that they were used to the way things had been, liked the way things had been, and were as unwilling as Jefferson had been to confront their own beliefs. Watching Robinson go 3-for-4 with a home run and a stolen base would have provided precisely that challenge. Along the way, so many other assumptions, some of them relatively recent (eugenics and devolution), about 600 years old (polygenesis, degeneration theory) or even older (the Curse of Ham) would have also been up for reevaluation.

Here we are again, despite those 3-for-4s and 12-strikeout games by Robinson, Luke Easter, Henry Aaron, Juan Soto, Juan Marichal, Mudcat Grant, David Price, and onward. The agenda then was to maintain things as they had been since the end of Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow. Today it is to turn a society which had been haltingly striving towards meritocracy, in which people are judged by what they can do rather than what they look like, back into a white supremacist society in which Americans are advantaged or disadvantaged by their skin color. They present a looking-glass inversion: instead of suffering harm due to bigotry, they argue that American minorities, whether of color, gender, or sexuality, have actually received undue benefits. When they go a step further and label a Robinson, an Ira Hayes, a Charles Calvin Rogers as “DEI,” they give away their true beliefs: it isn’t that some people of color or some people of alternative genders or sexuality have been unfairly advanced, they all have.

To persuade the public of this point, years of THEY CAN must be reverted to THEY CAN’T, even when THEY CAN’T is counterfactual. Thus must Robinson be expelled from the pantheon of great Americans and sent to the back of the cultural bus by being reclassified as DEI. He is a counterargument they can’t defeat—as he was undefeated by them in life—and so they must disappear him, as much to relieve their own cognitive dissonance, Jefferson style, as to induce amnesia in the rest of us.

Jackie Robinson said: “The most luxurious possession, the richest treasure anybody has, is his personal dignity.”

Jackie Robinson said: “I don’t think that I or any other Negro, as an American citizen, should have to ask for anything that is rightfully his.”

Jackie Robinson said: “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.”

That last is his epitaph. It’s why they are trying to take him away from us. If they succeed, he will only be the first part of our souls to be lost.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

And go look for a picture of the Enola Gay on government sites, which have been absurdly targeted because of the “G-word.”

As others have stated, please make this free and I'll share it everywhere I can.

Steve, I've enjoyed much of your work. But, never has your work been more essential in this country. Thank you.