“One of the frightening conclusions we have is that what separates honest people from not-honest people is not necessarily character, it’s opportunity.” — Dan Ariely, Professor of Psychology and Behavioral Economics, Duke University

Here is a lie the New York Mets told about first-base prospect Peter Alonso:

By itself, a team-told lie isn’t noteworthy. Teams lie all the time—the Mets especially, and often in weird ways. What’s different about this particular lie is the ways in which it’s clearly false.

A brief review of the roster reveals that “cannot find playing time” would be, if true, an egregious self-own of both the statement maker or the state of the Mets’ roster, such that if it were someone within our world of social media, all would agree they’d be best served by deleting their account. Another lie, implicit in this one, is the Mets’ need to get a look at Jay Bruce’s abilities at first base right now; Bruce is not only still recovering from his current spate of injuries (hip, foot), but is also under contract next year and would have spring training to show what he does or doesn’t offer at the position. Furthermore, Austin Jackson, whom this decision benefits the most, is a 31-year-old, late-July pickup who doesn’t serve a long-term purpose on a losing team, or really any team.

The reality is the Mets, no different than any other organization in baseball, are not promoting Alonso because if they wait until mid-April next season, they’ll secure an extra year of his services. Holding him back from playing in a lost season, plus a couple weeks of next year, is a small cost to pay for another year of control of a potentially very good hitter. It’s basically a no-brainer, as far as the on-field cost-benefit analysis goes. The short term is near meaningless for the Mets—it’s all about the future now. Even if they’re bad in five or six years, that extra controlled season can help get back more in a trade. So what’s the downside?

We often talk about baseball players in terms that separate their humanity from their production. They are “growth assets” or “sunk costs” or “$/WAR.” And those are fine to an extent—analyzing production is an important and necessary aspect of running a successful organization. But players are also people who are subject to the same emotions as we are when we fail to receive something we’ve worked for, and by all accounts deserve.

We don’t as often talk about the downsides of cold and calculated management—about how the Mets are enacting a potential disservice to themselves, souring their relationship with a player before he even reaches the majors, and putting him in the wrong mindset for success for the benefit of a right-right, high-maintenance bodied, first baseman’s age-31 season. About how this could backfire in terms of his performance, rendering moot these attempts to gain an extra year of service time. I could talk about all of that and it would all have merit, but it also is unnecessary, because in stark terms: what the Mets are doing is wrong.

Peter Alonso’s hardship is not on account of merit, but because the system, created by the owners and their commissioner, incentivizes the Mets to wrong him. Incentives are just that, though—incentives, not requirements. The Mets have a choice in this and they are choosing the one that penalizes an innocent player. As consumers of MLB’s product, we can both understand why organizations are taking these measures, while also taking a stand against them. By not allowing teams to disavow themselves from the moral choice they’re making in situations like the one with Alonso, consumers can work to influence team behaviors and rightfully reward players for holding up their end of the bargain. Baseball fans can work to make teams hold up theirs, too.

***

“The simplest reading of sports is that we want to see the extremes: how fast a human can throw it, how far a human can hit it. But that’s not quite true. If that’s what we wanted to see, we’d let the pitcher get a running start, we’d let the hitters use aluminum bats, we’d let them all drink Deca-Durabolin and we’d only make them play one game a week. We want to see the extremes when limitations are put on them. We want to see what they do when we make it hard.” — Sam Miller, ESPN

In video games, when things are going a little too easily, you can crank up the difficulty. This usually means enemies cause more damage, you have fewer lives, there are fewer weapons or ammunition available, and so on. Racing games have “rubber band” effects to help the cars behind catch up to the one in front. In Madden, the game cheats endlessly and now you have a broken controller. But when you do succeed at the highest level of difficulty, that success is more rewarding, the sense of accomplishment more grand.

In baseball, the solution to the problem of “how to win more games” became too simple for some. Finding the best available players and acquiring them via trade or by signing them in free agency did the job for a bit, but eventually it got too boring or easy and they kicked the difficulty setting up a notch: win more while spending less.

And like any game, the players (in this scenario, the GMs) have tackled the challenge of attempting to find the best ways to succeed given the golden rule (win more, spend less). First they targeted draft spending, with smaller-budget teams like the Royals spending over $10 million in the 2011 draft. A change to the CBA implemented harder slotting rules beginning in 2012, and that avenue was closed. Then teams turned to the international market as a way to get impact while not spending quite what you might on a free agent veteran, with teams like the Dodgers, Red Sox, Yankees, and Cubs busting their international budgets and incurring spending limitations the following years to sign large swaths of talent. A new CBA in 2017 saw an end put to that practice, with hard caps on international spending. All these changes were made in the spirit of “fairness,” without explicitly stating to whom things weren’t fair.

All of this was creativity pushing the given rules to an extreme. It might not seem so creative now, but the first teams to do it had others raising their eyebrows until they saw the sense it made and followed suit. What the front offices across the league did in terms of draft and international spending wasn’t cheating, per se. It was within the rules and carried consequences, but it was also taken to such an extreme that the owners saw fit to close those loopholes in the next CBAs, because those loopholes were costing them money.

***

“We find that when we look at personality tests of who cheats more, we thought maybe people who take more risks—maybe risk-takers cheat more … no. Maybe intelligent people … no. Creative people cheat more. And why do creative people cheat more? Because cheating is all about being able to tell a story about why what we want is actually okay.” — Dan Ariely, on Hidden Brain

One area that hasn’t been tamped down is the holding back of prospects (or early major leaguers, in the recent case of Byron Buxton) like Alonso, Eloy Jimenez, or Vladimir Guerrero Jr. This is in part because it saves ownership money, in part because the MLBPA hasn’t made it a major point of contention in negotiations, and in part because people who have used their creativity to finesse the system have crafted a narrative about why what they’re doing is actually okay. Ethics has given way to legality: the rules are the rules, and nothing beyond merits consideration.

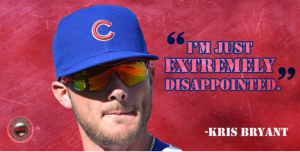

One other reason for the success of holding back prospects is that there hasn’t been much of a backlash from the prospects held back, in terms of refusals to sign extensions or playing hardball in arbitration. The most public example we have is Kris Bryant’s ongoing grievance against the Cubs.

Image credit: ESPN/Baseball Tonight

But boiling everything down to whether a guy walks away in free agency or goes hardline in arbitration ignores a lot of other factors that play into both of those decisions. Factors like team leverage, in the ability to offer life-changing money at a given moment that would provide long-term security if an arm or knee blows out, if they get the yips, or otherwise. Factors like our ability as people to forgive, or really, how exhausting it is to hold a grudge against your workplace for years on end, not to mention how distracting that might be in terms of one’s ability to perform at the highest level. Factors like anything beyond the good of the team itself.

And all of this sidesteps that we know, inherently, this is a poor way to treat people, that this is a way we would not want to be treated. Not everything that is rational is ethical. Not everything that is acceptable in moderation should be tolerated in the extreme. As fans, we cannot bargain with the players or ownership, we cannot write the terms of the CBA. We cannot enact a fix to the problem of teams intentionally fielding a lineup that isn’t their best because they’re incentivized not to. We can stop providing cover for these actions just because those incentives exist.

There is evidence that not excusing an organization’s behavior can affect their decision-making. The Pirates’ year-over-year attendance was down 5,475 people per game compared to 2017. This year, the Pirates made an aggressive deadline move to remain in the Wild Card hunt, trading for Chris Archer. Whether this was advisable is not relevant. The Pirates had failed to put their chips in the middle at the deadline in 2016-2017, with comparably slim chances at the playoffs. It is anecdotal evidence, true, but it’s difficult not to connect Pirates fans’ willingness to not attend because of their unhappiness with owner Bob Nutting and his refusal to spend in the offseason, with their front office’s willingness to finally make a move towards competitiveness—ill-advised as it may have been.

Promoting prospects when they’re ready doesn’t carry the same level of risk as a deadline trade, still gives the team six years to find a way to keep the player on a mid- or long-term solution, and it allows teams to field their most competitive units and fans to watch the best, most exciting players for the most amount of time.

Besides, it’s the right thing to do.

***

I wrote my first article for Baseball Prospectus as a fantasy team intern in August of 2013, and this is my last. I remember being so nervous about my first article that I stayed up til two or three in the morning, and ended up using the phrase “tautonymic mound-dwelling counterpart” (sorry about that Anthony Gose rec). For some reason they let me stay.

One of the funny things about being scared you don’t know enough to write for BP, is that … you definitely don’t. The longer you’re here, surrounded by some of the most compelling and intelligent authors and researchers, the more you realize you don’t know. That’s one of the biggest benefits of being here. It is a humbling, but worthwhile experience.

I’ve told a lot of the people I’ve brought on board that BP is very much what you make of it. It is a place that allowed me to grow from an intern to a staff writer, to a senior staff writer, to a prospect team member, then to editor. That was supposed to be a three-month stint. It lasted three years, and I’ve never been happier that inertia is a real thing.

I owe an incredible debt to more people than I can name or you want to read, but I hope you’ll indulge me a few (okay, a bunch [okay, a lot]). Thank you to Bret Sayre for bringing me on board and almost never saying no, even when you should have. To Ben Carsley for being the little brother I didn’t know I needed. To R.J. Anderson, for showing me how to write, and to Sam Miller for the confidence I never earned. To Patrick Dubuque, for always having the right words, and Meg Rowley, for the late-night laughs. To Jeffrey Paternostro, for being a giant pain in the ass, in the best way possible. Oh, and for the shots. To Jason Parks for The Moon. To Prospect Team Members past and present for their patience and their wisdom, but rarely their copy. To Bryan Grosnick, Zach Crizer, and Brendan Gawlowski for the brainstorming sessions, and to J.P. Breen for the constant encouragement. Thanks to James Fegan for telling me what Bernie is up to, and to Jason Wojciechowski for letting me be his alt. Thank you to Rob McQuown for the research assistance, and so, so, so much more. Thank you to my family for all the time you spent alone, as I wrote or edited an article.

I know I’m leaving people out. That’s the thing about BP: it’s given me so much. It’s not just a point of pride, which it is. It’s not just a way to scratch a baseball itch, which it is. It’s not just a passion project, which it very much is. It is a group of people who have become my community. A community I’m not sure what I’ll do without. I hope you treasure them as I have, because they deserve it.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

Damn, my work finally unblocked BP. This is terrible. For me.

It's probably good for you. I hope it's good for you. Leaving us to shill for QVC would be kind of an insult. Unless you were shilling 35 pounds of bison steaks like Tony Little. That would be must-see TV. Do that.

Also, tell me it's going to be okay with Yoan Moncada.

The way to solve the service time issue is to make every player a free agent after their XX age season. Teams will no longer have an incentive to keep players that can contribute today in the minors. The only down side is that some players will reach free agency after 1 or 2 years, while others will reach it after 7 or 8.

I don't blame teams for holding players back. Why bring Vlad Jr. up now, when you can wait until May 2019 and get the extra year?

going for it not in 16-17 but 2013, 14 & 15 when they were winning. Plus throwing money

at the inept front office & field management teams really has really PO'd the fans.

However holding back the prospects is not the result of evil GMs and owners. It is the unintended consequence of Union contract. If there were no service rules then the prospects would be brought up in September. If the Players Union wants to not count September against service time I am sure the Owners would love it.